Mitigating the Reproducibility Crisis in Neuroimaging Machine Learning: A Framework for Robust and Clinically Actionable Research

The integration of machine learning (ML) with neuroimaging data holds transformative potential for understanding and diagnosing psychiatric and neurological disorders.

Mitigating the Reproducibility Crisis in Neuroimaging Machine Learning: A Framework for Robust and Clinically Actionable Research

Abstract

The integration of machine learning (ML) with neuroimaging data holds transformative potential for understanding and diagnosing psychiatric and neurological disorders. However, this promise is undermined by a pervasive reproducibility crisis, driven by low statistical power, methodological flexibility, and improper model validation. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to enhance the rigor and reliability of their work. We first explore the root causes of irreproducibility, including the impact of small sample sizes and measurement reliability. We then detail methodological best practices, such as the NERVE-ML checklist, for transparent study design and data handling. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses common pitfalls like data leakage in cross-validation and p-hacking. Finally, we outline robust validation and comparative analysis techniques to ensure findings are generalizable and statistically sound. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging solutions, this review aims to equip the field with the tools needed to build reproducible, trustworthy, and clinically applicable neurochemical ML models.

Understanding the Crisis: Why Neuroimaging and Machine Learning Face a Reproducibility Challenge

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center is designed for researchers navigating the challenges of irreproducible research, particularly in neurochemical machine learning. The following guides and FAQs address specific, common issues encountered during experimental workflows.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our machine learning model achieved 95% accuracy on our internal test set, but performs poorly when other labs try to use it. What is the most likely cause?

- A: This is a classic sign of overfitting and a failure to use a proper lockbox (holdout) test set [1]. Internal performance estimates can be overly optimistic if the same data is used for model selection and final evaluation. On average, performance measured on a true lockbox is about 13% less accurate than performance measured through cross-validation alone [1]. Ensure your workflow includes a final, one-time evaluation on a completely held-out dataset that is never used during model development or training.

Q2: We set a random seed at the start of our code, but our deep learning results still vary slightly between runs. Why?

- A: Setting a random seed at the beginning of a script might not be sufficient to control all sources of randomness in complex deep learning libraries [2]. Different hardware, software versions, or non-deterministic algorithms can introduce variability. Best practice is to:

Q3: A reviewer asked us to prove our findings are "replicable," but I thought we showed they were "reproducible." What is the difference?

- A: These are distinct concepts [3] [4]:

- Reproducibility: The ability of an independent group to obtain the same results using the same input data, computational steps, methods, and code [2] [4]. It verifies the original analysis.

- Replicability: The ability of an independent group to reach the same conclusions by conducting a new study, collecting new data, and performing new analyses aimed at answering the same scientific question [3] [4]. It tests the generalizability of the finding.

Q4: What are the most common reasons for the reproducibility crisis in biomedical research?

- A: A survey of over 1,600 biomedical researchers identified the leading causes [5]. The top factors are summarized in the table below.

| Rank | Cause of Irreproducibility | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pressure to Publish ('Publish or Perish' Culture) | Leading Cause [5] |

| 2 | Small Sample Sizes | Commonly Cited [5] |

| 3 | Cherry-picking of Data | Commonly Cited [5] |

| 4 | Inadequate Training in Statistics | Contributes to Misuse [6] |

| 5 | Lack of Transparency in Reporting | Contributes to Irreproducibility [1] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Machine Learning Reproducibility

This guide helps you diagnose and fix common problems that prevent the reproduction of your machine learning results.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution | Protocol / Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| High performance in development, poor performance in independent validation. | Overfitting; no true lockbox test set; data leakage. | Implement a rigorous subject-based cross-validation scheme and a final lockbox evaluation [1]. | 1. Randomize dataset. 2. Partition data into training, validation (for model selection), and a final holdout (lockbox) set. 3. Use the lockbox only once at the end of the analysis [1]. |

| Inconsistent results when the same code is run on different systems. | Uncontrolled randomness; software version differences; silent default parameters. | Control the computational environment and document all parameters [2] [4]. | 1. Set and report random seeds for all random number generators. 2. Export and share the software environment (e.g., Docker container). 3. Report names and versions of all main software libraries [2]. |

| Other labs cannot reproduce your published model. | Lack of transparency; incomplete reporting of methods or data. | Adopt open science practices and detailed reporting [2]. | 1. Share code in an open repository (e.g., GitHub). 2. Use standardized data formats (e.g., BIDS for neuroimaging) [2]. 3. Provide a full description of data preprocessing, model architecture, and training hyperparameters [2]. |

| Statistical results are fragile or misleading. | Misuse of statistical significance (p-hacking); small sample size. | Improve statistical training and reporting [3] [6]. | 1. Pre-register study plans to confirm they are hypothesis-driven. 2. Report effect sizes and confidence intervals, not just p-values [3]. 3. Ensure studies are designed with adequate statistical power [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Implementing a Lockbox (Holdout) Validation for an ML Model

Objective: To reliably evaluate the generalizable performance of a machine learning model intended for biomedical use, avoiding the over-optimism of internal validation.

Materials: A labeled dataset, computing resources, machine learning software (e.g., Python, Scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch).

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Randomize the entire dataset. If the data has a nested structure (e.g., multiple samples per subject), perform partitioning at the subject level to prevent data leakage.

- Partitioning: Split the data into three distinct sets:

- Training Set (e.g., 70%): Used to train the model.

- Validation Set (e.g., 15%): Used for model selection and hyperparameter tuning.

- Lockbox (Test Set, e.g., 15%): Set aside and not used for any aspect of model development. It is accessed only once.

- Model Development: Iterate on model design and hyperparameter tuning using only the training and validation sets.

- Final Evaluation: Once the final model is selected, run it a single time on the lockbox set to obtain the performance estimate reported in the study [1].

Protocol 2: Ensuring Computational Reproducibility for a Deep Learning Experiment

Objective: To guarantee that the training of a deep learning model can be repeated to produce identical results.

Materials: Deep learning code, hardware with GPU, environment management tool (e.g., Conda, Docker).

Methodology:

- Environment Control:

- Document the OS, GPU model, CUDA version, and Python version.

- Use a virtual environment and export a list of all packages with their exact versions (e.g.,

pip freeze > requirements.txt). - For maximum reproducibility, create a Docker image of the entire environment [2].

- Randomness Control:

- Set random seeds for Python, NumPy, and the deep learning framework (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch) at the beginning of the script.

- Configure the framework to use deterministic algorithms, which may be slower but ensure reproducibility [2].

- Code and Data:

- Share the full source code in a public repository.

- Clearly document all data preprocessing steps and parameters. If possible, share the preprocessed data [2].

- Verification: Run the code multiple times in the controlled environment to verify that the output (e.g., final model weights, performance metrics) is identical.

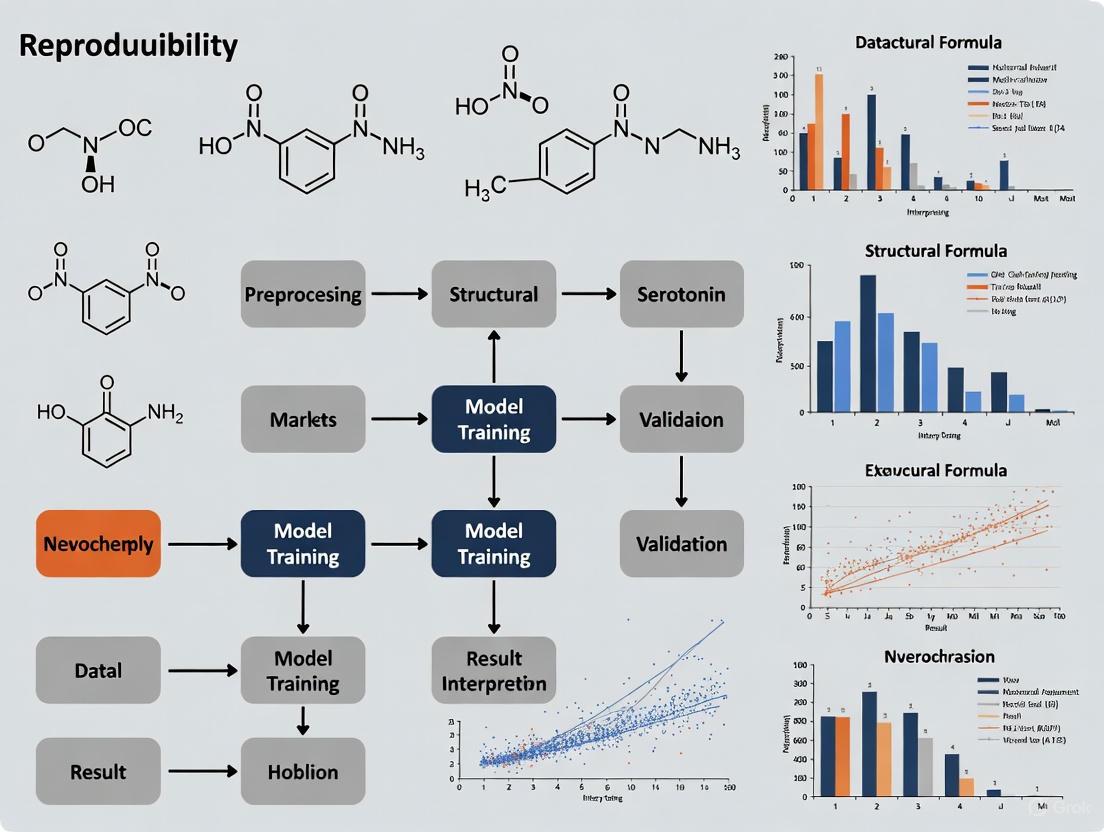

Visualizing the Workflow: Path to Reproducible ML

The following diagram illustrates a rigorous machine learning workflow designed to mitigate irreproducibility at key stages.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential "research reagents"—both conceptual and practical—that are critical for conducting reproducible neurochemical machine learning research.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Lockbox (Holdout) Test Set | A portion of data set aside and used only once for the final model evaluation. It provides an unbiased estimate of real-world performance [1]. |

| Random Seed | A number used to initialize a pseudo-random number generator. Setting this ensures that "random" processes (e.g., model weight initialization, data shuffling) can be repeated exactly [2] [4]. |

| Software Environment (e.g., Docker/Conda) | A containerized or virtualized computing environment that captures all software dependencies, ensuring that anyone can recreate the exact conditions under which the analysis was run [2]. |

| Subject-Based Cross-Validation | A validation scheme where data is split based on subject ID. This prevents inflated performance estimates that occur when data from the same subject appears in both training and test sets [2]. |

| Open Data Platform (e.g., OpenNeuro) | A repository for sharing neuroimaging and other biomedical data in standardized formats (like BIDS). Facilitates data reuse, multi-center studies, and independent validation [2]. |

| Version Control (e.g., GitHub) | A system for tracking changes in code and documentation. It is essential for collaboration, maintaining a history of experiments, and sharing the exact code used in an analysis [2]. |

| Statistical Power Analysis | A procedure conducted before data collection to determine the minimum sample size needed to detect an effect. It helps prevent underpowered studies, a major contributor to irreproducibility [3]. |

| Pre-registration | The practice of publishing the study hypothesis, design, and analysis plan in a time-stamped repository before conducting the experiment. It helps distinguish confirmatory from exploratory research [3]. |

Neuroimaging research, particularly when combined with machine learning for clinical applications, faces a trifecta of interconnected challenges that threaten the reproducibility and validity of findings. These issues—small sample sizes, high data dimensionality, and significant subject heterogeneity—collectively undermine the development of reliable biomarkers and the generalizability of research outcomes.

The reproducibility crisis in neuroimaging is well-documented, with studies revealing that only a small fraction of deep learning applications in medical imaging are reproducible [2]. This crisis stems from multiple factors, including insufficient sample sizes, variability in analytical methods, and the inherent biological complexity of neural systems. Understanding and addressing the three core challenges is fundamental to advancing robust, clinically meaningful neuroimaging research.

Quantitative Landscape: Understanding the Scale of the Problem

Sample Size Realities in Neuroimaging Research

Empirical studies of published literature reveal a significant disconnect between recommended and actual sample sizes in the field.

Table 1: Evolution of Sample Sizes in Neuroimaging Studies

| Study Period | Study Type | Median Sample Size | Trends & Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990-2012 | Highly Cited fMRI Studies | 12 participants | Single-group experimental designs [7] |

| 1990-2012 | Clinical fMRI Studies | 14.5 participants | Patient participation studies [7] |

| 1990-2012 | Clinical Structural MRI | 50 participants | Larger samples than functional studies [7] |

| 2017-2018 | Recent Studies in Top Journals | 23-24 participants | Slow increase (~0.74 participants/year) [7] |

The consequences of these small sample sizes are profound. Research demonstrates that replicability at typical sample sizes (N≈30) is relatively modest, and sample sizes much larger than typical (e.g., N=100) still produce results that fall well short of perfectly replicable [8]. For instance, one study found that even with a sample size of 121, the peak voxel in fMRI analyses failed to surpass threshold in corresponding pseudoreplicates over 20% of the time [8].

Impact of Sample Size on Replicability Metrics

Table 2: Sample Size Impact on Key Replicability Metrics

| Replicability Metric | Performance at N=30 | Performance at N=100 | Measurement Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voxel-level Correlation | R² < 0.5 | Modest improvement | Pearson correlation between vectorized unthresholded statistical maps [8] |

| Binary Map Overlap | Jaccard overlap < 0.5 | Jaccard overlap < 0.6 | Jaccard overlap of maps thresholded proportionally using conservative threshold [8] |

| Cluster-level Overlap | Near zero for some tasks | Below 0.5 | Jaccard overlap between binarized thresholded maps after cluster thresholding [8] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Core Challenges

FAQ: Small Sample Sizes

Q: What are the practical consequences of small sample sizes in neuroimaging studies?

A: Small samples dramatically reduce statistical power and replicability. They increase the likelihood of both false positives and false negatives, limit the generalizability of findings, and undermine the reliability of machine learning models. Studies with typical sample sizes (N≈30) show modest replicability, with voxel-level correlations between replicate maps often falling below R²=0.5 [8]. Furthermore, small samples make it difficult to account for the inherent heterogeneity of psychiatric disorders, potentially obscuring meaningful biological subtypes [9].

Q: What strategies can mitigate the limitations of small samples?

A: Several approaches can help optimize small sample studies:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply feature selection and extraction techniques before classification to reduce the feature space [10].

- Advanced Validation Methods: Utilize resubstitution with upper bound correction and appropriate cross-validation methods to optimize performance with limited data [10].

- Data Harmonization: Implement frameworks like those proposed by the Full-HD Working Group to combine datasets across sites, though this requires careful attention to acquisition and processing differences [11].

- Explainable AI: Employ techniques like Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to enhance interpretability and validate feature relevance even with limited data [10].

FAQ: High Dimensionality

Q: Why is high dimensionality particularly problematic in neuroimaging?

A: Neuroimaging data often involves thousands to millions of measurements (voxels, vertices, connections) per participant, creating a scenario known as the "curse of dimensionality" [10] [11]. When the number of features dramatically exceeds the number of participants, models become prone to overfitting, where they memorize noise in the training data rather than learning generalizable patterns. This leads to poor performance on independent datasets and inflated performance estimates in validation.

Q: What practical solutions exist for managing high-dimensional data?

A: Effective approaches include:

- Feature Selection and Extraction: Identify the most informative features or create composite measures that capture the essential information in fewer dimensions [10].

- Regularization Techniques: Implement mathematical constraints that prevent models from becoming overly complex during training.

- Specialized Software Tools: Utilize frameworks like HASE (High-Dimensional Analysis in Statistical Genetics) that are specifically designed for efficient processing of high-dimensional data, reducing computation time from years to hours in some cases [11].

- Multivariate Methods: Shift from mass univariate approaches to multivariate pattern analysis that considers distributed patterns of brain activity or structure [12].

FAQ: Subject Heterogeneity

Q: How does subject heterogeneity impact neuroimaging findings?

A: Psychiatric disorders labeled with specific DSM diagnoses often encompass wide heterogeneity in symptom profiles, underlying neurobiology, and treatment response [9]. For example, PTSD includes thousands of distinct symptom patterns across reexperiencing, avoidance, and hyper-arousal domains [9]. When neuroimaging studies treat heterogeneous patient groups as homogeneous, they may fail to identify meaningful biological signatures or develop models that work only for specific subgroups.

Q: What methods can address heterogeneity in research samples?

A: Promising approaches include:

- Data-Driven Subtyping: Apply clustering algorithms to identify neurobiologically distinct subgroups within diagnostic categories [9].

- Author-Topic Modeling: Use probabilistic modeling to automatically detect heterogeneities within meta-analyses that might arise from functional subdomains or disorder subtypes [13].

- Multi-Modal Integration: Combine information from structural, functional, and clinical measures to create more comprehensive patient profiles [9].

- Transdiagnostic Approaches: Look for patterns that cut across traditional diagnostic boundaries and better reflect the continuous nature of psychopathology.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol for Small Sample Machine Learning Studies

A study investigating sulcal patterns in schizophrenia (58 patients, 56 controls) provides a robust protocol for small sample machine learning research [10]:

- Feature Extraction: Process MRI scans using BrainVISA 5.0.4 with Morphologist 2021 pipeline to extract sulcal features from 49 cortical areas after quality control.

- Feature Normalization: Normalize features to zero mean and unit standard deviation, excluding outliers with values >6 standard deviations.

- Feature Selection/Extraction: Apply dimensionality reduction techniques to address the high feature-to-sample ratio.

- Classifier Comparison: Evaluate multiple machine learning and deep learning classifiers to identify the best-performing approach for the specific data.

- Validation: Implement rigorous validation methods, such as resubstitution with upper bound correction, to optimize performance given sample constraints.

- Interpretation: Apply explainable AI techniques (LIME, SHAP) to detect feature relevance and enhance biological interpretability.

Protocol for High-Dimensional Data Harmonization

The Full-HD Working Group established a framework for harmonizing high-dimensional neuroimaging phenotypes [11]:

- Quality Control: Generate mean gray matter density maps per cohort to verify consistent imaging processing pipelines across sites.

- Phenotype Screening: Filter phenotypes (e.g., voxels) that have little variation or may be erroneous, creating a mask for the analysis space.

- Partial Derivatives Approach: Apply meta-analysis algorithms that allow more insight into the data compared to classical meta-analysis.

- Centralized Storage: Store ultra-high-dimensional data on centralized servers using database formats like hdf5 for rapid access.

- Access Portal Development: Create online portals providing intuitive interaction with data for researchers not specializing in high-dimensional analysis.

Visualization: Analytical Workflows

High-Dimensional Data Analysis Pipeline

High-Dimensional Data Analysis Pipeline

Heterogeneity Assessment Framework

Heterogeneity Assessment Framework

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Addressing Neuroimaging Challenges

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| BrainVISA/Morphologist [10] | Sulcal Feature Extraction | Structural MRI Analysis | Automated detection, labeling, and characterization of sulcal patterns |

| HASE Software [11] | High-Dimensional Data Processing | Multi-site Imaging Genetics | Rapid processing of millions of phenotype-variant associations; quality control features |

| Author-Topic Model [13] | Heterogeneity Discovery | Coordinate-based Meta-analysis | Probabilistic modeling to identify latent patterns in heterogeneous data |

| CAT12 [9] | Structural Image Processing | Volume and Surface-Based Analysis | Automated preprocessing and feature extraction for structural MRI |

| fMRIPrep [9] | Functional MRI Preprocessing | Standardized Processing Pipeline | Robust, standardized preprocessing for functional MRI data |

| IB Neuro/IB Delta Suite [14] | Perfusion MRI Processing | DSC-MRI Analysis | Leakage-corrected perfusion parameter calculation; standardized maps |

Addressing the intertwined challenges of small samples, high dimensionality, and subject heterogeneity requires a multifaceted approach. Technical solutions include dimensional reduction, advanced validation methods, and data harmonization frameworks. Methodological improvements necessitate larger samples, pre-study power calculations, and standardized reporting. Conceptual advances demand greater attention to biological heterogeneity through data-driven subtyping and transdiagnostic approaches.

Improving reproducibility also requires cultural shifts within the research community, including adoption of open science practices, detailed reporting of methodological parameters, and commitment to replication efforts. As the field moves toward these solutions, neuroimaging will be better positioned to deliver on its promise of providing robust biomarkers and insights into brain function and dysfunction.

FAQs: Understanding Statistical Power and Reproducibility

1. What does it mean for a study to be "underpowered," and why is this a problem? An underpowered study is one that has a low probability (statistical power) of detecting a true effect, typically because it has too few data points or participants [15]. This practice is problematic because it leads to biased conclusions and fuels the reproducibility crisis [15]. Underpowered studies produce excessively wide sampling distributions for effect sizes, meaning the results from a single study can differ considerably from the true population value [15]. Furthermore, when such studies manage to reject the null hypothesis, they are likely to overestimate the true effect size, creating a misleading picture of the evidence [16] [17].

2. How does the misuse of power analysis contribute to a "vicious cycle" in research? A vicious cycle is created when researchers use inflated effect sizes from published literature (which are often significant due to publication bias) to plan their own studies [16]. Power analysis based on these overestimates leads to sample sizes that are too small to detect the true, smaller effect. If such an underpowered study nonetheless achieves statistical significance by chance, it will likely publish another inflated effect size, thus perpetuating the cycle of research waste and irreproducible findings [16].

3. What are Type M and Type S errors, and how are they related to low power? Conditional on rejecting the null hypothesis in an underpowered study, two specific errors become likely. A Type M (Magnitude) error occurs when the estimated effect size is much larger than the true effect size [17]. A Type S (Sign) error occurs when a study concludes an effect is in the opposite direction of the true effect [17]. Both errors are more probable when statistical power is low.

4. What unique reproducibility challenges does machine learning introduce? Machine learning (ML) presents unique challenges, with data leakage being a critical issue. Leakage occurs when information from outside the training dataset is inadvertently used to create the model, leading to overoptimistic and invalid performance estimates [18]. One survey found that data leakage affects at least 294 studies across 17 scientific fields [18]. Other challenges include the influence of "silent" parameters (like random seeds, which can inflate performance estimates by two-fold if not controlled) and the immense computational cost of reproducing state-of-the-art models [4].

5. When is it acceptable to conduct a study with a small sample size? Small sample sizes are sometimes justified for pilot studies aimed at identifying unforeseen practical problems, but they are not appropriate for accurately estimating an effect size [15]. While studying rare populations can make large samples difficult, researchers should explore alternatives like intensive longitudinal methods to increase the number of data points per participant, rather than accepting an underpowered design that cannot answer the research question [15].

6. What are the ethical implications of conducting an underpowered study? Beyond producing unreliable results, underpowered studies raise ethical concerns because they use up finite resources, including participant pools [15]. This makes it harder for other, adequately powered studies to recruit participants. If participants volunteer to contribute to scientific progress, participating in a study that is likely to yield misleading conclusions violates that promise [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Low Statistical Power in Study Design

This guide helps you diagnose and fix common issues leading to underpowered studies.

- Problem: Your experiment consistently fails to replicate published findings, or your effect size estimates are wildly inconsistent between studies.

- Explanation: The most likely cause is insufficient statistical power, often stemming from an overly optimistic expectation of the effect size or constraints on data collection.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action and Explanation |

|---|---|

| Identify & Define | Clearly state the primary hypothesis and the minimal effect size of interest (MESOI). The MESOI is the smallest effect that would be practically or clinically meaningful, not necessarily the largest effect you hope to see. |

| List Explanations | List possible causes for low power: • Overestimated Effect Size: Using an inflated effect from a previous underpowered study for sample size calculation. • Small Sample Size: Limited number of participants or data points. • High Variance: Noisy data or measurement error. • Suboptimal Analysis: Using a statistical model that does not efficiently extract information from the data. |

| Collect Data | Gather information: • Conduct a prospective power analysis using a conservative (small) estimate of the effect size. Use published meta-analyses for the best available estimate, if possible. • Calculate the confidence interval of your effect size estimate from a previous study; a wide interval signals high uncertainty. |

| Eliminate & Check | • To fix overestimation: Base your sample size on the MESOI or a meta-analytic estimate, not a single, exciting published result [16]. • To fix small N: Explore options for team science and multi-institutional collaboration to pool resources and increase sample size [16]. For ML, use publicly available datasets (e.g., MIMIC-III, UK Biobank) where possible [4]. • To reduce variance: Improve measurement techniques or use within-subject designs where appropriate [15]. |

| Identify Cause | The root cause is often a combination of factors, but the most common is an interaction between publication bias (which inflates published effects) and a resource-constrained research environment (which encourages small-scale studies) [16] [15]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving issues of low statistical power.

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Data Leakage in Machine Learning Projects

This guide helps you identify and prevent data leakage, a critical issue for reproducibility in ML-based science.

- Problem: Your ML model performs excellently during training and validation but fails dramatically when deployed on new, real-world data.

- Explanation: The most probable cause is data leakage, where information from the test set or external data inappropriately influences the training process [18].

| Troubleshooting Step | Action and Explanation |

|---|---|

| Identify & Define | The problem is a generalization failure. Define the exact boundaries of your training, validation, and test sets. |

| List Explanations | List common sources of leakage: • Preprocessing on Full Dataset: Performing feature selection or normalization before splitting data. • Temporal Leakage: Using future data to predict the past. • Batch Effects: Non-biological differences between batches that the model learns. • Duplicate Data: The same or highly similar samples appearing in both training and test sets. |

| Collect Data | • Create a model info sheet that documents exactly how and when every preprocessing step was applied [18]. • Audit your code for operations performed on the entire dataset prior to splitting. • Check for and remove duplicates across splits. |

| Eliminate & Check | • Implement a rigorous data pipeline: Ensure all preprocessing (e.g., imputation, scaling) is fit only on the training set and then applied to the validation/test sets. • Use nested cross-validation correctly if needed for hyperparameter tuning. • Set a random seed for all random processes (e.g., data splitting, model initialization) and report it to ensure reproducibility [4]. |

| Identify Cause | The root cause is typically a violation of the fundamental principle that the test set must remain completely unseen and uninfluenced by the training process until the final evaluation. |

The diagram below maps the process of diagnosing and fixing data leakage in an ML workflow.

Experimental Protocols for Robust Research

Protocol 1: Conducting a Prospective Power Analysis for a Neurochemical ML Study

Aim: To determine the appropriate sample size (number of subjects or data points) for a machine learning study predicting a neurochemical outcome (e.g., dopamine level) from neuroimaging data before beginning data collection.

Materials:

- Statistical software (e.g., R, Python, G*Power)

- Best available estimate of the expected effect size (from a meta-analysis or pilot study)

Methodology:

- Define the Primary Outcome: Clearly specify the model's performance metric that will be used to test the hypothesis (e.g., AUC-ROC, R², mean absolute error).

- Choose the Minimal Effect of Interest: Decide on the smallest improvement in this metric over a null model or previous standard that would be considered scientifically meaningful.

- Set Error Rates: Conventionally, set the Type I error rate (α) to 0.05 and the desired statistical power (1-β) to 0.80 or 0.90.

- Gather Effect Size Estimate: Crucially, obtain the effect size estimate from a meta-analysis or a previous large-scale study. If using a small pilot study, use the lower bound of the effect size's confidence interval to be conservative [16] [15].

- Perform Calculation: Use the appropriate function in your statistical software for the planned test (e.g., correlation, t-test, regression) to calculate the required sample size.

- Plan for Attrition: If the study is longitudinal, inflate the calculated sample size to account for expected participant dropout.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Leakage-Free ML Pipeline

Aim: To build a machine learning model for neurochemical prediction where the test set performance provides an unbiased estimate of real-world performance.

Materials:

- Dataset (e.g., neuroimaging data paired with neurochemical measures)

- Computing environment (e.g., Python with scikit-learn, TensorFlow, or PyTorch)

Methodology:

- Initial Split: Start by splitting the entire dataset into a holdout test set (e.g., 20%). This set is placed in a "vault" and not used for any aspect of model development or training [18].

- Preprocessing: Perform all preprocessing steps (feature scaling, imputation of missing values, feature selection) using only the training set. Fit the transformers (e.g., the

StandardScaler) on the training data and then use them to transform both the training and validation/test data. - Model Training & Validation: Use the remaining 80% of data for model training and hyperparameter tuning, ideally using a technique like k-fold cross-validation. Ensure that preprocessing is re-fit for each fold of the cross-validation using only that fold's training data.

- Final Evaluation: Once the final model type and hyperparameters are selected, train a model on the entire development set (the 80%) and evaluate it exactly once on the holdout test set from Step 1. This single performance metric on the test set is your unbiased estimate of model performance.

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from the literature on statistical power and reproducibility.

Table 1: Statistical Power and Effect Size Inflation in Scientific Research

| Field | Median Statistical Power | Estimated Effect Size Inflation | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychology | ~35% [15] | N/A | More than half of studies are underpowered, leading to biased conclusions and replication failures [15]. |

| Medicine (RCTs) | ~13% [16] | N/A | A survey of 23,551 randomized controlled trials found a median power of only 13% [16]. |

| Global Change Biology | <40% [16] | 2-3 times larger than true effect [16] | Statistically significant effects in the literature are, on average, 2-3 times larger than the true effect [16]. |

Table 2: Recommended Power Thresholds and Consequences

| Power Level | Type II Error Rate | Interpretation | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 80% (Nominal) | 20% | Conventional standard for an adequately powered study. | A 20% risk of missing a real effect (false negative) is considered acceptable. |

| 50% | 50% | Underpowered, similar to a coin toss. | High risk of missing true effects. If significant, high probability of overestimating the true effect (Type M error) [17]. |

| 35% (Median in Psych) | 65% | Severely underpowered [15]. | Very high risk of false negatives and effect size overestimation. Contributes significantly to the replication crisis [15]. |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Reproducible Science

| Item | Function | Example/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | Pre-collected, often curated datasets that facilitate replication and collaboration. | MIMIC-III (critical care data), UK Biobank (biomedical data), Phillips eICU [4]. |

| Open-Source Code | Publicly available analysis code that allows other researchers to exactly reproduce computational results. | Code shared via GitHub or as part of a CodeOcean capsule [18]. |

| Reporting Guidelines | Checklists to ensure complete and transparent reporting of study methods and results. | TRIPOD for prediction model studies, CONSORT for clinical trials, adapted for AI/ML [4]. |

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) | A formally designated group that reviews and monitors biomedical research to protect the rights and welfare of human subjects [19] [20]. | Required for all regulated clinical investigations; must have at least five members with varying backgrounds [19]. |

| Model Info Sheets | A proposed document that details how a model was trained and tested, designed to identify and prevent specific types of data leakage [18]. | A checklist covering data splitting, preprocessing, hyperparameters, and random seeds. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is measurement reliability, and why is it critical for neuroimaging studies? Measurement reliability, often quantified by metrics like the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), reflects the consistency of scores across replications of a testing procedure. It places an upper bound on the identifiable effect size between brain measures and behaviour or clinical symptoms. Low reliability introduces measurement noise, which attenuates true brain-behaviour relationships and can lead to failures in replicating findings, thereby directly contributing to the reproducibility crisis [21] [22].

FAQ 2: I can robustly detect group differences with my task. Why should I worry about its test-retest reliability for individual differences studies? This common misconception stems from conflating within-group effects and between-group effects. While a task may produce robust condition-wise differences (a within-group effect), its suitability for studying individual differences or classifying groups (between-group effects) depends heavily on its test-retest reliability. Both individual and group differences live on the same dimension of between-subject variability, which is directly affected by measurement reliability. Poor reliability attenuates observed between-group effect sizes, just as it does for correlational analyses [23].

FAQ 3: How does low measurement reliability specifically impact machine learning models in neuroimaging? In machine learning, low reliability in your prediction target (e.g., a behavioural phenotype) acts as label noise. This reduces the signal-to-noise ratio, which can:

- Increase uncertainty in parameter estimates and prolong training time.

- Cause models to fit variance of no interest (the noise) during training, leading to poor generalisation performance.

- Systematically reduce out-of-sample prediction accuracy, sometimes to the point of a complete failure to learn. Consequently, low prediction accuracy may stem from an unreliable target rather than a weak underlying brain-behaviour association [21].

FAQ 4: What are the most common sources of data leakage in ML-based neuroimaging science, and how can I avoid them? Data leakage inadvertently gives a model information about the test set during training, leading to wildly overoptimistic and irreproducible results. Common pitfalls include [24]:

- No Train-Test Split: Failing to create independent training and testing sets.

- Improper Pre-processing: Performing steps like feature selection or normalization on the entire dataset before splitting.

- Non-Independence: Having data from the same subject or related samples appear in both training and test sets.

- Temporal Leakage: Using data from the future to predict past events in time-series analyses.

- Illegitimate Features: Including features that are proxies for the outcome variable.

- Mitigation requires rigorous, subject-based data partitioning and ensuring all data preparation steps are defined solely on the training set.

FAQ 5: My sample size is large (N>1000). Does this solve my reliability problems? While larger samples can help stabilize estimates, they do not compensate for low measurement reliability. In fact, with highly unreliable measures, the benefits of increasing sample size from hundreds to thousands of participants are markedly limited. Only highly reliable data can fully capitalize on large sample sizes. Therefore, improving reliability is a prerequisite for effectively leveraging large-scale datasets like the UK Biobank [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Addressing Low Phenotypic Reliability

Problem: Poor prediction performance from brain data to behavioural measures, potentially due to unreliable behavioural assessments.

Diagnosis:

- Quantify Reliability: Calculate the test-retest reliability (e.g., ICC) for your key behavioural measures. The following table outlines common interpretations of ICC values [21]:

| ICC Range | Qualitative Interpretation |

|---|---|

| > 0.8 | Excellent |

| 0.6 - 0.8 | Good |

| 0.4 - 0.6 | Moderate |

| < 0.4 | Poor |

- Check the Literature: Be aware that reliability estimates reported in test manuals can be higher than those observed in large-scale, independent studies. Consult recent meta-analyses for realistic benchmarks [21].

Solutions:

- Improve the Measure: Use task versions optimized for reliability, aggregate across more trials, or use composite scores from multiple tasks to create a more reliable latent construct [21] [23].

- Select Reliable Targets: When designing a study, prioritize phenotypes with known high reliability (ICC > 0.8) for prediction modelling [21].

- Account for Attenuation: In your analysis, consider using statistical corrections for attenuation to estimate the true underlying effect size between variables, though this does not fix the prediction problem itself [21].

Guide 2: Preventing Data Leakage in Your Modelling Pipeline

Problem: Your model shows high performance during training and testing but fails completely when applied to new, external data.

Diagnosis: Follow a rigorous model info sheet to audit your own workflow. The checklist below helps identify common leakage points [24].

Solutions:

- Implement Subject-Based Splitting: Always split data by subject ID, never by trials or observations within a subject. Use cross-validation where subjects in the validation fold are entirely unseen during training.

- Pre-process After Splitting: Any step that uses data statistics (e.g., scaling, feature selection) must be fit on the training set and then applied to the validation/test set.

- Use Rigorous Data Partitioning: The following workflow diagram ensures a clean separation between training and test data throughout the machine learning pipeline:

Guide 3: Enhancing Reproducibility Through Open Science Practices

Problem: Other labs cannot reproduce your published analysis, or you cannot reproduce your own work months later.

Diagnosis: A lack of computational reproducibility stemming from incomplete reporting of methods, code, and environment.

Solutions:

- Share Code and Environment: Publicly release analysis code on platforms like GitHub. Specify the name and version of all main software libraries and, ideally, export the entire computational environment (e.g., as a Docker or Singularity container) [2] [25].

- Adopt Standardized Data Formats: Organize your raw data according to the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) standard. This simplifies data sharing, reduces curation time, and minimizes errors in analysis [25].

- Pre-register Studies: Submit your study hypothesis, design, and analysis plan to a pre-registration service before data collection begins. This limits researcher degrees of freedom and "p-hacking," leading to more robust findings [26] [25].

- Report Key Details: The table below lists critical experimental protocol information that must be included in your methods section or supplementary materials to enable replication [2]:

| Category | Key Information to Report |

|---|---|

| Dataset | Number of subjects, demographic data, data acquisition modalities (e.g., scanner model, sequence). |

| Data Pre-processing | All software used (with versions) and every customizable parameter (e.g., smoothing kernel size, motion threshold). |

| Model Architecture | Schematic representation, input dimensions, number of trainable parameters. |

| Training Hyperparameters | Learning rate, batch size, optimizer, number of epochs, random seed. |

| Model Evaluation | Subject-based partitioning scheme, number of cross-validation folds, performance metrics. |

Experimental Protocols for Reliability Assessment

Protocol 1: Simulating the Impact of Target Reliability on Prediction Accuracy

Objective: To empirically demonstrate how test-retest reliability of a behavioural phenotype limits its predictability from neuroimaging data.

Methodology:

- Base Data: Start with an empirical dataset (e.g., from HCP-A or UK Biobank) and select a highly reliable phenotype (e.g., age, grip strength) as your initial prediction target [21].

- Noise Introduction: Systematically add random Gaussian noise to the true phenotypic scores. The proportion of noise added determines the simulated reliability, calculated as:

ICC_simulated = σ²_between-subject / (σ²_between-subject + σ²_noise)[21]. - Prediction Modelling: For each level of simulated reliability, use a consistent ML model (e.g., linear regression, ridge regression) to predict the noisy phenotype from brain features (e.g., functional connectivity matrices).

- Performance Evaluation: Track out-of-sample prediction accuracy (e.g., R², MAE) as a function of the simulated reliability. This will show a clear decrease in accuracy as reliability drops.

The following diagram illustrates this workflow:

Protocol 2: A Practical Checklist for Reliable ML-based Neuroimaging

Objective: To provide a actionable list of "research reagent solutions" that serve as essential materials for conducting reproducible, reliability-conscious research.

| Item Category | Specific Item / Solution | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Data & Phenotypes | Pre-registered Analysis Plan | Limits researcher degrees of freedom; reduces HARKing (Hypothesizing After Results are Known). |

| Phenotypes with Documented High Reliability (ICC > 0.7) | Ensures the prediction target has sufficient signal for stable individual differences modelling [21]. | |

| BIDS-Formatted Raw Data | Standardizes data structure for error-free sharing, re-analysis, and reproducibility [25]. | |

| Computational Tools | Version-Control System (e.g., Git) | Tracks all changes to analysis code, enabling full audit trails and collaboration. |

| Software Container (e.g., Docker/Singularity) | Captures the complete computational environment, guaranteeing exact reproducibility [2]. | |

| Subject-Level Data Splitting Script | Prevents data leakage by automatically ensuring no subject's data is in both train and test sets [24]. | |

| Reporting & Sharing | Model Info Sheet / Checklist | A self-audit document justifying the absence of data leakage and detailing model evaluation [24]. |

| Public Code Repository (e.g., GitHub) | Allows peers to inspect, reuse, and build upon your work, verifying findings [2] [25]. | |

| Shared Pre-prints & Negative Results | Disseminates findings quickly and combats publication bias, giving a more accurate view of effect sizes. |

Modern academia operates within a "publish or perish" culture that often prioritizes publication success over methodological rigor. This environment creates a fundamental conflict of interest where the incentives for getting published frequently compete with the incentives for getting it right. Researchers face intense pressure to produce novel, statistically significant findings to secure employment, funding, and promotion, which can inadvertently undermine the reproducibility of scientific findings [27] [28] [29]. This problem is particularly acute in emerging fields like neurochemical machine learning, where complex methodologies and high-dimensional data increase the vulnerability to questionable research practices.

The replication crisis manifests when independent studies cannot reproduce published findings, threatening the very foundation of scientific credibility. Surveys indicate that more than 70% of researchers have tried and failed to reproduce another scientist's experiments, and more than half have failed to reproduce their own experiments [30]. This crisis stems not from individual failings but from systemic issues in academic incentive structures that reward publication volume and novelty over robustness and transparency.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the "reproducibility crisis" in scientific research?

The reproducibility crisis refers to the widespread difficulty in independently replicating published scientific findings using the original methods and materials. This crisis affects numerous disciplines and undermines the credibility of scientific knowledge. Surveys show the majority of researchers acknowledge a significant reproducibility problem in contemporary science [30] [31]. In neurochemical machine learning specifically, challenges include non-transparent reporting, data leakage, inadequate validation, and model overfitting that can create the illusion of performance where none exists.

How do academic incentives contribute to this problem?

Academic career advancement depends heavily on publishing in high-impact journals, which strongly prefer novel, positive, statistically significant results. This creates a "prisoner's dilemma" where researchers who focus exclusively on rigorous, reproducible science may be at a competitive disadvantage compared to those who prioritize publication volume [29]. The system rewards quantity and novelty, leading to practices like p-hacking, selective reporting, and hypothesizing after results are known (HARKing) that inflate false positive rates [27] [28].

What are "Questionable Research Practices" (QRPs)?

QRPs are methodological choices that increase the likelihood of false positive findings while maintaining a veneer of legitimacy. Common QRPs include:

- P-hacking: Trying multiple analytical approaches until statistically significant results emerge

- HARKing: Presenting unexpected findings as if they were hypothesized all along

- Selective reporting: Publishing only studies that "worked" while omitting null results

- Inadequate power: Using small sample sizes that detect effects only when they are inflated These practices are often motivated by publication pressure rather than malicious intent [28].

What solutions exist to counter these problematic incentives?

The open science movement promotes practices that align incentives with reproducibility:

- Pre-registration: Publishing study designs and analysis plans before data collection

- Registered Reports: Peer review before results are known

- Data and code sharing: Making materials available for independent verification

- Power analysis: Justifying sample sizes a priori

- Replication studies: Valuing confirmatory research alongside novel findings [28] [31]

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Addressing Reproducibility Problems

Problem 1: Publication Bias and the File Drawer Effect

Symptoms: Literature shows predominantly positive results; null findings rarely appear; meta-analyses suggest small-study effects.

| Root Cause | Impact on Reproducibility | Diagnostic Check |

|---|---|---|

| Journals prefer statistically significant results | Creates distorted literature; overestimates effect sizes | Conduct funnel plots; check for missing null results in literature |

| Career incentives prioritize publication count | Researchers avoid submitting null results | Calculate fail-safe N; assess literature completeness |

| Grant funding requires "promising" preliminary data | File drawer of unpublished studies grows | Search clinical trials registries; compare planned vs. published outcomes |

Solution Protocol:

- Pre-register all studies at Open Science Framework or similar platform before data collection

- Submit for Registered Report review where available

- Publish null results in specialized journals or preprint servers

- Include published and unpublished studies in meta-analyses

Problem 2: P-hacking and Analytical Flexibility

Symptoms: Effect sizes decrease with larger samples; statistical significance barely crosses threshold (p-values just under 0.05); multiple outcome measures without correction.

| Practice | Reproducibility Risk | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|

| Trying multiple analysis methods | Increased false positives | Compare different analytical approaches on same data |

| Adding covariates post-hoc | Model overfitting | Use holdout samples; cross-validation |

| Optional stopping without adjustment | Inflated Type I error | Sequential analysis methods |

| Outcome switching | Misleading conclusions | Compare preregistration to final report |

Solution Protocol:

- Pre-specify primary analysis in preregistration document

- Use holdout samples for exploratory analysis

- Blind data analysis where possible

- Document all analysis decisions regardless of outcome

Problem 3: Inadequate Statistical Power

Symptoms: Wide confidence intervals; failed replication attempts; effect size inflation in small studies.

| Field | Typical Power | Reproducibility Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroscience | ~20% | High false negative rate; inflated effects |

| Psychology | ~35% | Limited detection of true effects |

| Machine Learning | Varies widely | Overfitting; poor generalization |

Solution Protocol:

- Conduct a priori power analysis for smallest effect size of interest

- Plan for appropriate sample sizes considering multiple comparisons

- Use sequential designs when feasible

- Collaborate across labs for larger samples

Problem 4: Insfficient Methodological Detail

Symptoms: Inability to implement methods from description; code not available; key parameters omitted.

| Omission | Impact | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperparameter settings | Prevents model recreation | Share configuration files |

| Data preprocessing steps | Introduces variability | Document all transformations |

| Exclusion criteria | Selection bias | Pre-specify and report all exclusions |

| Software versions | Dependency conflicts | Use containerization (Docker) |

Solution Protocol:

- Use methodological checklists (e.g., CONSORT, TRIPOD)

- Share analysis code with documentation

- Use version control for all projects

- Create reproducible environments with containerization

| Tool Category | Specific Resources | Function in Promoting Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Preregistration Platforms | Open Science Framework, ClinicalTrials.gov | Document hypotheses and analysis plans before data collection |

| Data Sharing Repositories | Dryad, Zenodo, NeuroVault | Archive and share research data for verification |

| Code Sharing Platforms | GitHub, GitLab, Code Ocean | Distribute analysis code and enable collaboration |

| Reproducible Environments | Docker, Singularity, Binder | Containerize analyses for consistent execution |

| Reporting Guidelines | EQUATOR Network, CONSORT, TRIPOD | Standardize study reporting across disciplines |

| Power Analysis Tools | G*Power, pwr R package, simr | Determine appropriate sample sizes before data collection |

Experimental Protocols for Enhancing Reproducibility

Protocol 1: Preregistration of Neurochemical Machine Learning Studies

Purpose: To create a time-stamped research plan that distinguishes confirmatory from exploratory analysis.

Materials: Open Science Framework account, study design materials.

Procedure:

- Define primary research question with specific hypotheses

- Specify experimental design including participant/sample characteristics

- Detail data collection procedures with quality control measures

- Define primary and secondary outcomes with measurement methods

- Specify analysis pipeline including preprocessing, feature selection, and model validation

- Document exclusion criteria for data quality

- Upload to preregistration platform before data collection or analysis

Validation: Compare final manuscript to preregistration to identify deviations.

Protocol 2: Power Analysis for Machine Learning Studies

Purpose: To ensure adequate sample size for reliable effect detection.

Materials: Preliminary data or effect size estimates, statistical software.

Procedure:

- Identify primary outcome and analysis method

- Determine smallest effect size of theoretical interest

- Set desired power (typically 80-90%) and alpha level (typically 0.05)

- Account for multiple comparisons with appropriate correction

- For machine learning: Consider cross-validation scheme and hyperparameter tuning in power calculation

- For neurochemical studies: Account for measurement reliability and within-subject correlations

- Calculate required sample size using simulation if standard formulas don't apply

Validation: Conduct sensitivity analysis to determine detectable effect sizes.

Protocol 3: Data and Code Sharing Preparation

Purpose: To enable independent verification of findings.

Materials: Research data, analysis code, documentation templates.

Procedure:

- Anonymize data to protect participant confidentiality

- Create comprehensive codebook with variable definitions

- Clean and annotate analysis code with section headers and comments

- Create README file with setup instructions and dependencies

- Choose appropriate repository for data type and discipline

- Select license for data and code reuse

- Upload all materials with persistent identifier (DOI)

Validation: Ask a colleague to recreate analysis using only shared materials.

Addressing the reproducibility crisis requires systemic reform of academic incentive structures. While individual researchers can adopt practices like preregistration and open data, lasting change requires institutions, funders, and journals to value reproducibility alongside innovation. This includes recognizing null findings, supporting replication studies, and using broader metrics for career advancement beyond publication in high-impact journals.

Movements like the Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) advocate for reforming research assessment to focus on quality rather than journal impact factors [29]. Similarly, initiatives like Registered Reports shift peer review to focus on methodological rigor before results are known. By realigning incentives with scientific values, we can build a more cumulative, reliable, and efficient research enterprise—particularly crucial in high-stakes fields like neurochemical machine learning where reproducibility directly impacts drug development and patient outcomes.

Building Robust Pipelines: Best Practices for Reproducible Study Design and Execution

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the NERVE-ML Checklist and why is it needed in neural engineering? The NERVE-ML (neural engineering reproducibility and validity essentials for machine learning) checklist is a framework designed to promote the transparent, reproducible, and valid application of machine learning in neural engineering. It is needed because the incorrect application of ML can lead to wrong conclusions, retractions, and flawed scientific progress. This is particularly critical in neural engineering, which faces unique challenges like limited subject numbers, repeated or non-independent samples, and high subject heterogeneity that complicate model validation [32] [33].

Q2: What are the most common causes of failure in ML-based neurochemical research? The most common causes of failure and non-reproducibility stem from data leakage and improper validation procedures. A comprehensive review found that data leakage alone has affected hundreds of papers across numerous scientific fields, leading to wildly overoptimistic conclusions [24]. Specific pitfalls include:

- No train-test split

- Feature selection performed on the combined training and test sets

- Use of illegitimate features that would not be available in real-world deployment

- Pre-processing data before splitting into training and test sets [34] [24]

Q3: How does the NERVE-ML checklist address the "theory-free" ideal in ML? The checklist provides a structured approach that explicitly counters the notion that ML can operate as a theory-free enterprise. It emphasizes that successful inductive inference in science requires theoretical input at key junctures: problem formulation, data collection and curation, model design, training, and evaluation. This is crucial because ML, as a formal method of induction, must rely on conceptual or theoretical resources to get inference off the ground [35].

Q4: What practical steps can I take to prevent data leakage in my experiments?

- Ensure a clean separation between training and test datasets during all pre-processing, modeling, and evaluation steps [34]

- Carefully evaluate whether features used for training would be legitimately available when making predictions on new data in real-world scenarios [24]

- Use the Model Info Sheet template proposed by reproducibility researchers to document and justify the absence of leakage in your work [24]

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Performance and Failed Generalization

Problem: Your model performs well on training data but fails to generalize to new neural data, or performance is significantly worse than reported in literature.

Diagnosis and Solution Protocol:

| Step | Action | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Overfit a single batch | Drive training error arbitrarily close to 0; failure indicates implementation bugs, incorrect loss functions, or numerical instability [36]. |

| 2 | Verify data pipeline | Check for incorrect normalization, data augmentation errors, or label shuffling mistakes that create a train-test mismatch [36]. |

| 3 | Check for data leakage | Ensure no information from test set leaked into training; review feature selection and pre-processing steps [24]. |

| 4 | Compare to known results | Reproduce official implementations on benchmark datasets before applying to your specific neural data [36]. |

| 5 | Apply NERVE-ML validation | Use appropriate validation strategies that account for neural engineering challenges like subject heterogeneity and non-independent samples [32]. |

Issue 2: Data Quality and Preprocessing Problems

Problem: Model performance is unstable, or you suspect issues with neural data quality, labeling, or feature engineering.

Diagnosis and Solution Protocol:

| Step | Action | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Handle missing data | Remove or replace missing values; consider the extent of missingness when choosing between removal or imputation [37]. |

| 2 | Address class imbalance | Check if data is skewed toward specific classes or outcomes; use resampling or data augmentation techniques for balanced representation [37]. |

| 3 | Detect and treat outliers | Use box plots or statistical methods to identify values that don't fit the dataset; remove or transform outliers to stabilize learning [37]. |

| 4 | Normalize features | Bring all features to the same scale using normalization or standardization to prevent some features from dominating others [37]. |

| 5 | Apply feature selection | Use Univariate/Bivariate selection, PCA, or Feature Importance methods to identify and use only the most relevant features [37]. |

Issue 3: Irreproducible Results and Implementation Errors

Problem: Inability to reproduce your own results or published findings, or encountering silent failures in deep learning code.

Diagnosis and Solution Protocol:

| Step | Action | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Start simple | Begin with a simple architecture (e.g., LeNet for images, LSTM for sequences) and sensible defaults before advancing complexity [36]. |

| 2 | Debug systematically | Check for incorrect tensor shapes, improper pre-processing, wrong loss function inputs, and train/evaluation mode switching errors [36]. |

| 3 | Ensure experiment tracking | Use tools like MLflow or W&B to track code, data versions, metrics, and environment details for full reproducibility [38]. |

| 4 | Validate with synthetic data | Create simpler synthetic datasets to verify your model should be capable of solving the problem before using real neural data [36]. |

| 5 | Document with model info sheets | Use standardized documentation to justify the absence of data leakage and connect model performance to scientific claims [24]. |

Systematic Troubleshooting Workflow

Quantitative Evidence: The Reproducibility Crisis in ML-Based Science

The following data, compiled from a large-scale survey of reproducibility failures, demonstrates the pervasive nature of these issues across scientific fields:

| Field | Papers Reviewed | Papers with Pitfalls | Primary Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropsychiatry | 100 | 53 | No train-test split; Pre-processing on train and test sets together [24] |

| Medicine | 71 | 48 | Feature selection on train and test set [24] |

| Radiology | 62 | 39 | No train-test split; Pre-processing; Feature selection; Illegitimate features [24] |

| Law | 171 | 156 | Illegitimate features; Temporal leakage; Non-independence between sets [24] |

| Neuroimaging | 122 | 18 | Non-independence between train and test sets [24] |

| Molecular Biology | 59 | 42 | Non-independence between samples [24] |

| Software Engineering | 58 | 11 | Temporal leakage [24] |

| Family Relations | 15 | 15 | No train-test split [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Protocol 1: Proper Train-Test Splitting for Neural Data

Objective: To create validation splits that accurately estimate real-world performance while accounting for the unique structure of neural engineering datasets.

Methodology:

- Account for subject heterogeneity: Ensure splits maintain similar distributions of relevant clinical or experimental variables across training and test sets [33]

- Handle repeated measurements: When multiple samples come from single individuals, keep all samples from each subject entirely within either training or test sets to prevent leakage [32]

- Address temporal dependencies: For time-series neural data, use forward-chaining validation where the test set always occurs chronologically after the training set [24]

- Validate split representativeness: Statistically compare the distributions of key variables between training and test splits to ensure they represent the same population [33]

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Model Evaluation Using NERVE-ML

Objective: To evaluate ML models not just on predictive performance but on their ability to produce valid, reproducible scientific conclusions.

Methodology:

- Multiple validation strategies: Compare results across k-fold cross-validation, subject-wise splitting, and temporal splitting to identify potential overfitting [33]

- Ablation studies: Systematically remove potentially illegitimate features to assess their contribution to performance [24]

- Baseline comparison: Ensure ML models significantly outperform simple baselines (e.g., linear models, population averages) to justify their complexity [36]

- Error analysis: Characterize performance across different subpopulations, experimental conditions, or subject demographics to identify failure modes [32]

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Neural Engineering ML |

|---|---|

| MOABB (Mother of All BCI Benchmarks) | Standardized framework for benchmarking ML algorithms in brain-computer interface research, enabling reproducibility and cross-dataset comparability [33] |

| Model Info Sheets | Documentation framework for detecting and preventing data leakage by requiring researchers to justify the absence of leakage and connect model performance to scientific claims [24] |

| Experiment Tracking Tools (MLflow, W&B) | Systems to track code, data versions, metrics, and environment details to guarantee reproducibility across research iterations [38] |

| Data Version Control (DVC, lakeFS) | Tools for versioning datasets and managing data lineage, essential for debugging and auditing ML pipelines at scale [38] |

| Feature Stores (Feast, Michelangelo) | Platforms to manage, version, and serve features consistently between training and inference to prevent skew and ensure model reliability [38] |

| Synthetic Data Generators | Tools to create simpler synthetic training sets for initial model validation and debugging before using scarce or complex real neural data [36] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Data Use Agreements (DUAs)

Q1: What is a Data Use Agreement (DUA) and when is it required? A Data Use Agreement (DUA), also referred to as a Data Sharing Agreement or Data Use License, is a document that establishes the terms and conditions under which a data provider shares data with a recipient researcher or institution [39] [40]. It is required when accessing non-public, restricted data, such as administrative data or sensitive health information, for research purposes [40]. A DUA defines the permitted uses of the data, access restrictions, security protocols, data retention policies, and publication constraints [39].

Q2: Our DUA negotiations have been ongoing for over a year. How can we avoid such delays? Delays are common, especially with new data sharing relationships. To mitigate this [39]:

- Investigate Sharing History: Inquire if the data provider has shared this data before and request a copy of a previous DUA to use as a starting template [39].

- Prepare Documentation Early: Draft a letter detailing the data requested, planned uses, data management plan, and proposed redistribution or destruction policies, even if the provider doesn't require it initially [39].

- Understand Provider Constraints: Recognize that data providers, especially government agencies, may be resource-constrained and have legal review processes. Be transparent about your timeline and budget for potential data preparation fees [39].

Q3: What are the most critical components to include in a DUA to ensure compliant and reproducible research? A comprehensive DUA should align with frameworks like the Five Safes to manage risk [39]:

- Safe Projects: Clearly define the approved project scope and research purpose.

- Safe People: Specify researcher qualifications, required training, and institutional affiliations.

- Safe Settings: Detail the secure computing environment and data access controls (e.g., secure servers, VPNs).

- Safe Data: List the specific data elements being shared and any de-identification or anonymization techniques applied.

- Safe Outputs: Establish procedures for reviewing and approving all outputs (e.g., papers, reports) to prevent privacy breaches through statistical disclosure [39].

Ethical Approvals and Compliance

Q4: What are the key ethical principles we should consider when designing a neurochemical ML study? Core ethical principles for brain data research are [41]:

- Autonomy: Respect for individual decision-making, often operationalized through informed consent, where the purpose of data collection and use is clearly explained [41].

- Justice: Avoiding bias and discrimination, and ensuring fairness in data representation and clinical trial enrollment [41].

- Non-maleficence: Avoiding potential harms, such as privacy breaches or inadequate safety testing. This requires rigorous validation to avoid oversights, akin to historical drug safety failures [41].

- Beneficence: Promoting social well-being by ensuring the research ultimately serves human health [41].

Q5: Our project involves international collaborators. How do we navigate differing data governance regulations? Global collaboration introduces challenges due to differing ethical principles and laws (e.g., GDPR vs. HIPAA) [42] [43].

- Acknowledge Pluralism: Recognize that ethical and legal principles vary between jurisdictions. A one-size-fits-all approach is not feasible [42].

- Implement a Federated Governance Model: Consider frameworks, like that of the International Brain Initiative (IBI), which aim to balance data protection with open science for international collaboration without necessarily centralizing the data [43].

- Clarify Data Definitions: Ensure all parties have a shared understanding of key terms. For example, confirm whether "de-identified" data is considered equivalent to "anonymized" data across the relevant legal domains [42].

Troubleshooting Reproducibility

Q6: Despite using a published method, we cannot reproduce the original study's results. What are the most likely causes? This is a common manifestation of the reproducibility crisis. Likely causes include [26] [31] [44]:

- Insufficient Methodological Detail: The original paper may not have provided enough information on data pre-processing, model architecture, or hyperparameters [26].

- Data Leakage: A faulty procedure may have allowed information from the training set to leak into the test set, inflating the original performance metrics [26].

- Uncontrolled Researcher Degrees of Freedom: The original authors may have tried many different architectures or analysis procedures before arriving at the final method, leading to overfitting and results that do not generalize [26] [31].

- Inadequate Statistical Power: The original study may have been too small, leading to imprecise results and inflated effect sizes that are unlikely to replicate [31] [44].

Q7: How can we structure our data management to make our own ML research more reproducible?

- Create a "Readme" File: Document the basics of the study, data collection methods, and known limitations [31] [44].

- Develop a Data Dictionary: Provide clear descriptions for all variables in your dataset [31].

- Use Version Control: For code and analysis scripts, use systems like Git and host them on platforms like GitHub or the Open Science Framework (OSF) [31].

- Adopt Standardized Pipelines: Where possible, use pre-existing, community-standardized analysis pipelines to protect against analytical flexibility and "p-hacking" [31].

Experimental Protocols for Reproducible Research

Protocol 1: Pre-Registration of Study Design

Pre-registration is the practice of publishing a detailed study plan before beginning research to counter bias and improve robustness [31].

Detailed Methodology:

- Define Hypotheses: Clearly state your primary research question and specific, testable hypotheses.

- Specify Methods: Describe the study population, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and data sources. For ML models, pre-specify the core architecture and family of algorithms to be used.

- Outline Analysis Plan: Declare your primary and secondary outcomes. Pre-specify the data pre-processing steps, feature engineering, and the statistical test or evaluation metric that will determine the success of the primary hypothesis.

- Sample Size Justification: Perform an a-priori power analysis using tools like G*Power to determine the sample size needed to detect a realistic effect, rather than using convenience samples [31] [44].

- Deposit Plan: Submit this plan to a pre-registration service (e.g., the Open Science Framework, AsPredicted) before any data analysis begins [31].

Protocol 2: Distinguishing Confirmatory from Exploratory Analysis

Mixing confirmatory and exploratory analysis without disclosure is a major source of non-reproducible findings [31].

Detailed Methodology:

- Separate Analyses: In your research documentation and publications, clearly label which analyses and statistical tests were pre-specified in your pre-registration (confirmatory) and which were conceived after looking at the data (exploratory).

- Report Appropriately: For confirmatory analyses, report p-values and significance tests as planned. For exploratory analyses, only describe the observed patterns or effects in the data; avoid reporting p-values or presenting them as hypothesis tests [31].

- Generate New Hypotheses: Frame the results of exploratory analyses as new hypotheses that require future pre-registered studies for confirmation.

Data Governance Workflow for Reproducible ML

The following diagram illustrates the key stages and decision points in a responsible data governance workflow for a machine learning research project.

Table 1: Key resources and reagents for navigating data governance and ensuring reproducible research outcomes.

| Resource / Reagent | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| Data Use Agreement (DUA) Templates [39] [40] | Provides a standardized structure to define terms of data access, use, security, and output, reducing negotiation time and ensuring comprehensiveness. |

| Five Safes Framework [39] | A risk-management model used to structure DUAs and data access controls around Safe Projects, People, Settings, Data, and Outputs. |

| Open Science Framework (OSF) [31] | A free, open-source platform for project management, collaboration, sharing data and code, and pre-registering study designs. |

| G*Power Software [31] [44] | A tool to perform a-priori power analysis for determining the necessary sample size to achieve adequate statistical power, mitigating false positives. |

| Statistical Disclosure Control | A set of methods (e.g., rounding, aggregation, suppression) applied before publishing results to protect subject privacy and create "safe outputs" [39]. |

| Data Dictionary [31] | A document describing each variable in a dataset, its meaning, and allowed values, which is critical for data understanding and reproducibility. |