Illuminating the Brain: A Comprehensive Guide to Protein-Based Fluorescent Probes for Neurotransmitter Imaging

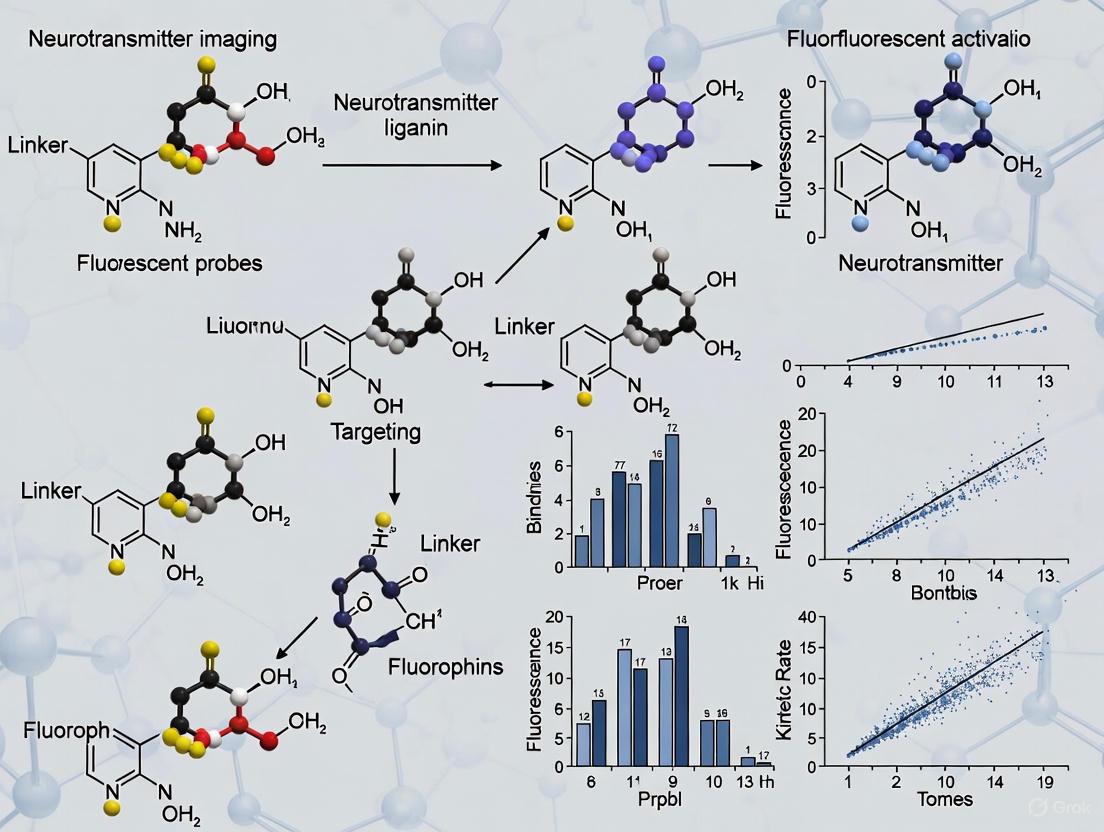

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the development, application, and future of protein-based fluorescent probes for imaging neurotransmitters.

Illuminating the Brain: A Comprehensive Guide to Protein-Based Fluorescent Probes for Neurotransmitter Imaging

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the development, application, and future of protein-based fluorescent probes for imaging neurotransmitters. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of genetically encoded biosensors, detailing their design and mechanisms, such as FRET and conformational changes. The scope extends to methodological applications in disease models like depression and addiction, troubleshooting for optimization in live-cell imaging, and a critical comparative analysis with other sensor technologies. By synthesizing current research and challenges, this review serves as a vital resource for advancing neuroscience toolkits and accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

The Foundation of Fluorescent Neuroimaging: Understanding Genetically Encoded Probes

Protein-based fluorescent probes are indispensable tools in modern neuroscience and drug development, enabling the real-time visualization of neurotransmitters and intracellular signaling dynamics. The core function of these biosensors relies on a fundamental biochemical process: a specific ligand-binding event triggering a precise conformational change within the protein, which in turn modulates its fluorescent output. Understanding the mechanisms behind this coupling—often described by the paradigms of induced fit and conformational selection—is critical for interpreting experimental data and engineering next-generation probes with improved sensitivity, kinetics, and specificity [1] [2]. This Application Note details the core principles and provides actionable protocols for studying these mechanisms, framed within the context of neurotransmitter imaging research.

Core Binding Mechanisms and Energetics

Ligand-binding mechanisms are characterized by the temporal order of the conformational change relative to the binding event. The two primary models are described in the table below.

Table 1: Fundamental Ligand-Binding Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Temporal Sequence | Key Feature | Energetic Driver |

|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Fit [3] | Ligand binds first → Protein conformation changes afterward | The ligand actively "induces" a new conformation; the closed state is rarely sampled without ligand. | Binding energy is used to overcome the barrier for the conformational change. |

| Conformational Selection [2] | Protein conformation changes first → Ligand binds to pre-formed state | The ligand "selects" a pre-existing, low-population conformation from the protein's dynamic ensemble. | The ligand stabilizes a high-energy conformation, shifting the equilibrium. |

These mechanisms are not always mutually exclusive; a protein may utilize a combination of both pathways. However, they represent two idealized endpoints on a spectrum. The reverse process (unbinding) sees the mechanism flip: the reverse of an induced-fit binding pathway is unbinding via conformational selection, and vice versa [2].

The following diagram illustrates the sequential steps of these two primary mechanisms and their relationship.

Quantitative Analysis of Binding Dynamics

The kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of ligand binding provide definitive evidence for distinguishing the underlying mechanism. Single-molecule studies have quantified these effects in model systems.

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Parameters from Model Systems

| Protein System | Observed Effect of Ligand Binding | Quantitative Change | Inferred Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| FeuA (Bacterial SBP) [1] | Shifts conformational equilibrium to closed state. | Accelerates closing 10,000-fold; stabilizes closed state 250-fold. | Primarily Induced Fit |

| GlnBP (E. coli Glutamine-Binding Protein) [3] | Ligand binding and conformational changes are highly correlated; no detectable unliganded closed states. | Binding kinetics consistent with a dominant induced-fit model. | Primarily Induced Fit |

| General Two-State Protein [2] | The dominant relaxation rate into equilibrium depends on ligand concentration. | For Induced Fit: ( k{\text{obs}} \approx k{\text{on}}[L] + k{\text{off}} ) For Conformational Selection: ( k{\text{obs}} \approx \frac{k{\text{on}}[L]}{K{\text{eq}} + [L]} + k_{\text{off}} ) | Varies |

Experimental Protocols for Mechanism Elucidation

This section provides a detailed methodology for using single-molecule Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (smFRET) to simultaneously observe ligand binding and conformational changes, a powerful approach for distinguishing between binding mechanisms.

Protocol: smFRET Assay for Coupled Binding and Conformation

Principle: A protein is site-specifically labeled with a donor (e.g., Alexa555) and an acceptor (e.g., Alexa647) fluorophore. Ligand binding is often detected via quenching of one fluorophore, while conformational changes are detected as a change in FRET efficiency due to altered distance between the donor and acceptor [1].

Workflow Overview: The following diagram outlines the major experimental and analytical steps in this protocol.

Materials

- Recombinant Protein: Purified protein (e.g., FeuA, GlnBP) with two engineered solvent-accessible cysteine residues for labeling [1] [3].

- Fluorophores: Maleimide-reactive donor and acceptor dyes (e.g., Alexa555, Alexa647). Aliquot and store desiccated at -20°C, protected from light.

- Ligand: High-purity ligand of interest (e.g., ferri-bacillibactin for FeuA, L-glutamine for GlnBP). Prepare a stock solution in appropriate buffer.

- Buffers:

- Labeling Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM KCl.

- Imaging Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM KCl. Filter through a 0.2 µm membrane before use.

- Equipment:

- Confocal microscope equipped for smFRET and Alternating Laser Excitation (ALEX) with 532 nm and 637 nm laser lines.

- Single-photon avalanche diodes (SPADs) for detection.

- Size-exclusion chromatography system (e.g., Superdex 200).

Procedure

Protein Labeling and Purification: a. Reduce purified protein with 10 mM DTT for 30 minutes at 4°C to ensure cysteines are free. b. Immobilize protein on Ni2+-Sepharose resin and wash with 10 column volumes of labeling buffer to remove DTT. c. Incubate resin with a 20-fold molar excess of dyes (dissolved in labeling buffer) for 2-8 hours at 4°C in the dark. d. Wash away unbound dye with 20 column volumes of labeling buffer. e. Elute labeled protein with 400 mM imidazole. f. Further purify by size-exclusion chromatography to remove aggregates and free dye. Determine labeling efficiency and concentration by absorbance spectroscopy [1].

smFRET Data Acquisition: a. Dilute labeled protein to 25-100 pM in imaging buffer to achieve single-molecule conditions. b. For ligand titration, add increasing concentrations of ligand to the protein sample. c. Using the ALEX microscope, focus the lasers 20 µm into the solution. Collect fluorescence data using a pulsed interleaved excitation pattern (e.g., 50 µs alternation between 532 nm and 637 nm lasers). d. Record photon arrival times for both donor and acceptor channels for at least 300 seconds per condition [1] [3].

Data Analysis: a. Burst Identification: Identify bursts of photons corresponding to single molecules diffusing through the laser focus. b. FRET Efficiency Calculation: For each burst, calculate FRET efficiency as ( E{FRET} = IA / (ID + IA) ), where ( IA ) and ( ID ) are the acceptor and donor intensities, respectively. c. Ligand Binding Analysis: Simultaneously monitor acceptor fluorophore quenching (if applicable) to determine ligand occupancy for each molecule. d. Correlation: Construct combined FRET efficiency vs. ligand occupancy histograms to visualize the coupling between binding and conformation [1]. e. Kinetic Analysis: For molecules showing dynamics, extract transition rates between high-FRET and low-FRET states using hidden Markov modeling or similar tools. Global analysis of rates across ligand concentrations allows discrimination between induced-fit and conformational selection models [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogues key materials and their applications in studying ligand-induced conformational changes in fluorescent proteins.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Specific Labeling Dyes (e.g., Alexa555, Alexa647) [1] | Covalent attachment to engineered cysteine residues for smFRET. Provides the donor-acceptor pair for distance measurement. | smFRET studies on FeuA to correlate domain closure (FRET change) with ferri-bacillibactin binding (quenching). |

| Genetically Encoded Biosensors (e.g., GCaMP, iGABASnFR) [4] | All-in-one probes where a ligand-binding domain is fused to a fluorescent protein; ligand binding alters fluorescence. | iGABASnFR for real-time imaging of GABA neurotransmitter release in vivo in mouse models and zebrafish. |

| Ratiometric Small-Molecule Probes (e.g., PBN-5) [5] | Synthetic probes that bind an analyte (e.g., norepinephrine) and produce a shift in emission wavelength (ratiometric signal). | Quantitative detection of norepinephrine in plasma and urine, and visualization in tissues for hypertension research. |

| Alternating Laser Excitation (ALEX) Microscopy [1] | Advanced fluorescence microscopy technique that separates diffusing species based on their labeling stoichiometry, reducing artifacts in smFRET. | Identifying and analyzing only doubly-labeled, intact protein complexes in smFRET experiments. |

| Stable Protein Crystallization Reagents [3] | Lipidic cubic phase matrices, fusion protein tags, and stabilizing mutations used to obtain high-resolution structures of intermediate states. | Determining atomic structures of apo (open) and holo (closed) states of GlnBP to inform mechanistic models. |

Application in Neurotransmitter Probe Development

The principles of induced fit and conformational selection directly inform the design and interpretation of experiments using fluorescent protein-based probes for neurotransmitter imaging.

- Probe Design and Optimization: Understanding that a ligand can selectively stabilize a pre-existing conformation (conformational selection) justifies screening for mutations in the binding protein that pre-populate the active state, potentially leading to probes with higher ligand affinity or faster on-rates [2].

- Interpreting Sensor Output: Many genetically encoded neurotransmitter sensors, such as the GRABDA (GPCR Activation-Based Sensor) family and iGluSnFR (glutamate sensor), utilize conformational changes in native receptor proteins fused to fluorescent proteins [4]. The kinetics of the fluorescent response are directly governed by the underlying ligand-binding mechanism of the receptor domain.

- Mechanism of Ratiometric Probes: The dual-site ratiometric probe for norepinephrine (PBN-5) is a prime example of applied induced fit. The probe's two recognition sites (aldehyde and boronic acid) simultaneously bind the ligand's unique moieties, inducing the formation of a rigid, macrocyclic structure. This conformational change restricts molecular motion, leading to a measurable ratiometric fluorescence shift [5]. This design strategy ensures high specificity and accuracy for quantitative detection in complex biological fluids like plasma and urine.

By integrating these core principles of protein-ligand interactions, researchers can better design experiments, engineer improved molecular tools, and accurately decode the dynamic language of neuronal communication.

Genetically encoded biosensors based on fluorescent proteins (FPs) are indispensable tools for studying biological processes in living systems, particularly in the challenging context of neurotransmitter imaging in the brain [6] [7]. These sensors convert biochemical events into detectable optical signals, allowing real-time monitoring of cellular parameters with high spatial and temporal resolution [6]. A significant breakthrough in biosensor engineering was the development of circularly permuted FPs (cpFPs), which addressed a fundamental limitation of native FPs: their N- and C-termini are located in flexible regions far from the chromophore, hampering efficient conformational coupling with sensory units [6]. This architectural innovation has enabled the creation of sensitive probes for visualizing neurotransmitters, second messengers, and other analytes critical for understanding brain function and drug development [8] [7].

Core Sensor Architectures and Design Principles

Fundamental Classes of Fluorescent Protein-Based Biosensors

Genetically encoded fluorescent indicators (GEFIs) can be classified into several architectural groups, each with distinct mechanisms and applications [6]. The choice of design depends on the study's objective and the specific parameter to be measured.

Table: Key Architectures for Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Indicators

| Architecture | Mechanism | Key Features | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single FP-based (without sensory domain) | Direct interaction of analyte with chromophore [6] | Simple design, low molecular weight [6] | pH [6], halide ions [6] |

| Single FP-based (with sensory domain) | Conformational change in sensory domain affects chromophore [6] | Target specificity, can be integrated with cpFPs [6] | Ca²⁺, neurotransmitters [6] [7] |

| FRET-based | Modulation of energy transfer between two FPs [6] [7] | Ratiometric measurement, reduced artifacts [7] | Ca²⁺, cAMP, protease activity [7] |

| Circularly Permuted FP (cpFP)-based | Sensory domains fused to new termini near chromophore [6] | High dynamic range, sensitive to conformational changes [6] | Ca²⁺ (e.g., G-CaMP), voltage, glutamate [6] [9] [7] |

The Principle of Circular Permutation

Circular permutation involves fusing the original N- and C-termini of a FP with a peptide linker and creating new termini in a different region of the sequence, often in a loop near the chromophore [6] [9]. This restructuring imparts greater mobility to the FP compared to its native variant, making the chromophore's environment more labile and sensitive to external changes [6]. When a sensory domain (e.g., calmodulin for calcium) is fused to these new termini, the conformational rearrangement upon analyte binding is directly transmitted to the chromophore, resulting in a measurable change in fluorescence [6] [9]. This design overcomes the rigidity of the native FP β-barrel structure that otherwise insulates the chromophore [6].

Quantitative Comparison of Key Fluorescent Proteins

The performance of a biosensor is critically dependent on the photophysical properties of its underlying fluorescent protein. Engineering efforts, including circular permutation and directed evolution, aim to optimize these parameters for specific imaging applications.

Table: Photophysical Properties of Representative Fluorescent Proteins and cpFPs

| Fluorescent Protein | Type | Excitation (nm) | Emission (nm) | Brightness (Relative) | Key Features / Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFP (Aequorea victoria) | Native | 395, 475 [6] | 509 [6] | Baseline | First discovered FP, forms basis for many sensors [6] |

| mCherry | Native (RFP) | 587 [9] | 610 [9] | 100% [9] | Monomeric red FP, used as template for cpRFPs [9] |

| cp193 (mCherry-derived) | Circularly Permuted | ~580 [9] | ~602 [9] | 4% (of mCherry) [9] | Initial permuted variant with low brightness [9] |

| cp193g7 (evolved) | Circularly Permuted (Evolved) | 580 [9] | 602 [9] | 69% (of mCherry) [9] | Directed evolution improved folding & brightness [9] |

| G-CaMP (GCaMP2) | cpFP-based Sensor (Green) | ~488 | ~510 | N/A | Kd ~0.15 μM for Ca²⁺ [7]; widely used Ca²⁺ sensor [7] |

Experimental Protocol: Developing and Validating a cpFP-Based Biosensor

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating a functional biosensor by integrating a sensory domain with a circularly permuted fluorescent protein, based on established protein engineering methodologies [6] [9].

Sensor Construction and Molecular Cloning

- Select cpFP Scaffold: Choose a well-characterized cpFP (e.g., a circularly permuted green fluorescent protein or the evolved red cp193g7 [9]) with known bright fluorescence and good folding efficiency.

- Identify Fusion Points: Determine the optimal sites within the sensory domain (e.g., a neurotransmitter-binding protein) for inserting the cpFP. This often requires structural data or testing of several flexible linker regions [6] [9].

- Generate Genetic Construct: Use standard molecular biology techniques (e.g., PCR, Gibson Assembly) to create a single open reading frame encoding the final biosensor: Sensory Domain - cpFP - Sensory Domain.

- Clone into Expression Vector: Insert the assembled construct into an appropriate mammalian expression vector containing a promoter (e.g., CMV, CAG) for subsequent transfection and imaging.

Functional Screening and Characterization

- Heterologous Expression: Express the biosensor construct in a relevant cell line (e.g., HEK293T) via transient transfection.

- Primary Fluorescence Screening: Use fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry to identify cells expressing the biosensor. Screen for constructs that display bright fluorescence, indicating successful folding and chromophore maturation [9].

- Stimulus Application: Expose the cells to the target analyte (e.g., specific neurotransmitter, Ca²⁺ ionophore) while performing live-cell imaging.

- Response Quantification: Measure the change in fluorescence intensity (ΔF/F₀) upon analyte application. Sensors with a high signal-to-noise ratio and reproducible responses are selected for further characterization [7].

- Determine Key Parameters:

- Dynamic Range: Calculate (Fmax - Fmin) / Fmin, where Fmax and F_min are the fluorescence intensities in the presence of saturating and zero analyte, respectively.

- Affinity (Kd): Determine the dissociation constant by measuring the sensor's response to a range of analyte concentrations and fitting the data to a binding curve [7].

- Kinetics: Measure the sensor's response time (on-rate) and recovery time (off-rate) after rapid addition and removal of the analyte.

Validation in Biological Systems

- Targeted Expression: Express the validated biosensor in primary neurons or brain slices using viral vectors (e.g., AAV) or transgenic approaches [7].

- Functional Imaging: Perform live imaging (e.g., confocal or two-photon microscopy) to monitor biosensor activity in response to physiological stimuli, such as electrical or pharmacological stimulation to evoke neurotransmitter release [7].

- Specificity and Cytotoxicity Tests: Verify that the sensor does not respond to unrelated analytes and does not perturb normal cell function (e.g., buffering of the native signaling molecule).

Applications in Neurotransmitter Imaging and Brain Research

The development of cpFP-based biosensors has been pivotal for advancing our understanding of neurochemical signaling. These sensors are now used to image a wide range of neurotransmitters and second messengers in the brain with high spatiotemporal resolution [7].

Table: Key Neurotransmitter Targets and Associated Sensor Architectures

| Analyte / Process | Sensor Name / Class | Architecture | Key Application in Neuroscience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium (Ca²⁺) | GCaMP series [7] | cpGFP with Ca²⁺-sensing domains [6] [7] | Monitoring neuronal and astrocytic activity in vivo [7] |

| Voltage | cpFP-based voltage sensors [6] | cpFP inserted into voltage-sensitive domain [6] [9] | Detecting membrane potential changes in single neurons [6] |

| Glutamate | iGluSnFR [8] | cpGFP with glutamate-binding protein [8] | Imaging synaptic glutamate release [8] |

| Monoamines (DA, 5-HT, NE) | GRAB, SRAB sensors [8] | cpGFP with GPCR-based sensing domains [8] | Tracking dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine dynamics in behaving animals [8] |

| cAMP | FRET-based & single FP sensors [7] | Various, including cpFP integration [7] | Visualizing second messenger signaling cascades [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for cpFP Biosensor Development and Application

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Circularly Permuted FP Genes | Scaffold for sensor construction; provides the fluorescent readout [6] [9] | cpGFP for GCaMP; cp-mCherry (cp193g7) for red sensors [9] [7] |

| Sensory Domain Plasmids | Provides analyte specificity (e.g., calmodulin for Ca²⁺, GPCRs for neurotransmitters) [6] [8] | Fused to cpFP to create the complete biosensor [6] [8] |

| Mammalian Expression Vectors | Plasmid for expressing the biosensor construct in cells [7] | Transient transfection in HEK cells for initial testing [7] |

| Viral Vectors (AAV, Lentivirus) | Efficient delivery of biosensor genes into neurons and brain tissue in vivo [7] | Stereotactic injection for stable expression in specific brain regions [7] |

| Synthetic Ca²⁺ Indicators | Chemical sensors for benchmarking and complementary imaging [7] | Compare performance of GCaMP with Oregon Green BAPTA-1 or Cal-520 [7] |

| Two-Photon Microscopy Systems | Essential for deep-tissue, high-resolution imaging in live brains [7] | Monitoring sensor activity in cortical layers of behaving mice [7] |

Fluorescent biosensors have become indispensable tools in modern neuroscience and drug development, enabling the real-time visualization of neurochemical dynamics with high spatiotemporal resolution. The core functionality of these probes relies on sophisticated fluorescence mechanisms that convert molecular recognition events into measurable optical signals. Among the most critical of these mechanisms are Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET), and Intramolecular Charge Transfer (ICT). These fundamental photophysical processes allow researchers to monitor neurotransmitters, neuromodulators, and intracellular signaling events in living cells, intact tissues, and even behaving animals [10] [11] [12]. The strategic implementation of these mechanisms in protein-based probe design has revolutionized our ability to dissect the complex spatiotemporal dynamics of neuronal communication, providing unprecedented insights into brain function and dysfunction [8] [13].

The selection of an appropriate fluorescence mechanism is paramount in biosensor engineering, as it directly impacts critical performance parameters including sensitivity, specificity, dynamic range, and kinetic properties. FRET-based sensors excel at reporting conformational changes and molecular interactions, PET mechanisms offer excellent signal-to-noise ratios for small molecule detection, and ICT-based designs provide environmentally sensitive reporters that respond to local chemical changes [11] [14]. For researchers investigating neurotransmitter signaling, understanding the operational principles, advantages, and limitations of each mechanism is essential for proper experimental design, data interpretation, and tool selection. This article provides a comprehensive overview of these essential fluorescence mechanisms, with specific application to protein-based probes for neurotransmitter imaging, along with detailed protocols for their implementation in neuroscientific research.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Their Applications

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)

Principles and Mechanism

FRET is a distance-dependent quantum mechanical phenomenon involving the non-radiative transfer of energy from an excited donor fluorophore to a proximal acceptor fluorophore through dipole-dipole coupling [10] [11]. For FRET to occur efficiently, three critical conditions must be met: (1) significant spectral overlap between the donor emission spectrum and the acceptor absorption spectrum (known as the overlap integral, J(λ)), (2) proper relative orientation of the donor and acceptor transition dipoles (κ²), and (3) close proximity between the donor and acceptor, typically within the 1-10 nm range [10]. The efficiency of FRET (E) exhibits an inverse sixth-power relationship with the distance between fluorophores (R), described by the fundamental FRET equation:

E = 1/[1 + (R/R₀)⁶] [10]

where R₀ represents the Förster distance at which energy transfer efficiency is 50%. The value of R₀ can be calculated using the equation:

R₀ = 8.79 × 10⁻⁵ × [n⁻⁴ × Q × κ² × J(λ)] [10]

where n is the refractive index of the medium, Q is the quantum yield of the donor in the absence of the acceptor, κ² is the orientation factor, and J(λ) is the spectral overlap integral [10]. This strong distance dependence makes FRET an exquisitely sensitive molecular ruler for monitoring conformational changes in biosensors, protein-protein interactions, and cleavage events in living systems.

Applications in Neurotransmitter Sensing

FRET-based biosensors have been widely employed for monitoring neurotransmitter dynamics and intracellular signaling pathways in neuroscience research. A prominent application involves the development of genetically encoded FRET biosensors for tracking the activity of key signaling molecules such as PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), a critical regulator of neuronal growth and synaptic plasticity [15]. These sensors typically employ cyan (CFP) and yellow (YFP) fluorescent protein variants as FRET pairs, with the conformational state of PTEN modulating the distance and orientation between the fluorophores, thereby altering FRET efficiency [15]. When PTEN adopts its closed, inactive conformation, the fluorophores are in close proximity, resulting in high FRET efficiency. Upon transition to the open, active conformation, the increased distance between fluorophores reduces FRET efficiency, providing a quantifiable readout of PTEN activity in real-time [15].

FRET-based neurotransmitter sensors have also been engineered using periplasmic binding proteins (PBPs) as recognition elements. These sensors typically consist of a neurotransmitter-binding domain sandwiched between donor and acceptor fluorescent proteins. Ligand binding induces a conformational change in the PBP that alters the relative orientation and distance between the fluorophores, modulating FRET efficiency [12]. This design strategy has been successfully applied to develop sensors for various neurotransmitters, including glutamate (iGluSnFR), acetylcholine (iAChSnFR), and monoamines, enabling researchers to monitor neurotransmission with exceptional spatiotemporal resolution in diverse experimental preparations, from cultured neurons to behaving animals [13] [12].

Figure 1: FRET Mechanism. Energy transfer from an excited donor fluorophore to an acceptor fluorophore occurs without photon emission, leading to sensitized acceptor emission.

Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET)

Principles and Mechanism

PET is an electron-transfer process that functions as an effective "on-off" switch for fluorescence [10] [11] [14]. In PET-based sensors, the mechanism involves the transfer of an electron from a receptor unit (electron donor) to an excited fluorophore (electron acceptor) upon photoexcitation. This electron transfer quenches the fluorescence of the fluorophore by providing a non-radiative relaxation pathway for the excited state electron [10] [14]. The recognition unit, typically containing atoms with lone electron pairs (such as nitrogen or oxygen), serves as the electron donor. When the target analyte binds to the recognition unit, it reduces the electron-donating ability of the receptor, thereby suppressing the PET process and restoring fluorescence in a "turn-on" response [11] [14]. This efficient quenching mechanism makes PET-based sensors exceptionally sensitive, with the ability to detect target analytes at nanomolar or even picomolar concentrations in some applications.

PET can operate through two distinct pathways: reductive PET and oxidative PET. In reductive PET, the fluorophore acts as an electron acceptor, with electrons transferring from the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of the recognition unit to the HOMO of the excited fluorophore. Conversely, in oxidative PET, the fluorophore serves as an electron donor, with electrons transferring from the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the fluorophore to the LUMO of the analyte or recognition unit [11]. The efficiency of PET depends on several factors, including the redox potentials of the donor and acceptor units, their spatial separation, and the conformational flexibility of the molecular scaffold. Careful optimization of these parameters enables the design of PET-based sensors with large fluorescence enhancement factors and excellent signal-to-noise ratios, making them particularly valuable for detecting low-abundance neurotransmitters in complex biological environments.

Applications in Neurotransmitter Sensing

PET-based fluorescent sensors have found extensive application in detecting metal ions and small molecule neurotransmitters, particularly monoamines such as dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine [14]. These sensors often incorporate recognition elements with specific binding affinity for the target neurotransmitter, such as boronic acid groups for diol-containing compounds or metal chelators for cationic neurotransmitters. The binding event modulates the electron-donating capacity of the recognition unit, leading to fluorescence enhancement that can be quantified to determine neurotransmitter concentration [14].

For neuronal imaging applications, PET-based sensors can be engineered into cell-permeable synthetic probes or genetically encoded designs. Synthetic PET sensors often utilize environmentally sensitive fluorophores such as quinoline or BODIPY derivatives, whose photophysical properties can be finely tuned through structural modifications [14]. These small molecule probes can be deployed in acute brain slices or in vivo through localized application, allowing real-time monitoring of neurotransmitter dynamics with high temporal resolution. Genetically encoded PET sensors typically employ circularly permuted fluorescent proteins (cpFPs) coupled to neurotransmitter-binding domains such as G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) [13] [12]. In these designs, neurotransmitter binding induces conformational rearrangements that alter the local environment of the chromophore, modulating fluorescence through PET or other mechanisms. The GRAB (GPCR Activation-Based) family of sensors exemplifies this approach, providing robust tools for monitoring dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, and acetylcholine release with high specificity and sensitivity in defined neuronal populations [13] [12].

Figure 2: PET Mechanism. (Left) Without analyte, electron transfer from receptor to fluorophore quenches fluorescence. (Right) Analyte binding blocks PET, restoring fluorescence.

Intramolecular Charge Transfer (ICT)

Principles and Mechanism

ICT represents a fundamental photophysical process in which electronic charge redistribution occurs within a molecule upon photoexcitation [11] [14]. ICT-based sensors typically feature a conjugated molecular system with distinct electron-donating and electron-accepting groups connected through a π-conjugated bridge, creating a "push-pull" electronic structure [11]. When the molecule absorbs a photon, the excited state exhibits significant charge separation, with electron density shifting from the donor to the acceptor group. This charge redistribution profoundly influences the photophysical properties of the fluorophore, including absorption and emission spectra, fluorescence quantum yield, and excited-state lifetime [11] [14].

The sensitivity of ICT-based probes to their local environment makes them particularly valuable for biological sensing applications. Changes in polarity, viscosity, pH, or specific molecular interactions can alter the efficiency of the ICT process, resulting in measurable shifts in emission wavelength (color) or intensity [11]. For instance, in more polar environments, the charge-separated excited state is often stabilized, leading to a redshift in emission spectrum and potentially reduced fluorescence quantum yield due to enhanced non-radiative decay pathways. This environmental sensitivity enables the design of rationetric sensors that measure the ratio of fluorescence at two different wavelengths, providing a built-in correction for variations in probe concentration, excitation intensity, and detection efficiency [14]. The ability to perform rationetric measurements makes ICT-based sensors highly robust for quantitative imaging applications in heterogeneous biological samples.

Applications in Neurotransmitter Sensing

ICT-based fluorescent sensors have been successfully developed for detecting various neurotransmitters, particularly those with functional groups capable of modulating the electron-donating or accepting properties of the fluorophore [14]. For example, sensors for catecholamines like dopamine and norepinephrine often incorporate boronic acid receptors that form cyclic esters with the catechol diol structure. This binding event alters the electron-withdrawing character of the receptor, inducing a spectral shift in the ICT fluorophore that can be detected through rationetric imaging or color changes [14]. Similarly, pH-sensitive ICT probes have been utilized to monitor synaptic activity indirectly through local pH changes associated with neurotransmitter release and recycling.

In the context of protein-based probes, ICT principles have been incorporated into genetically encoded sensors through several innovative strategies. One approach involves the fusion of pH-sensitive fluorescent proteins to synaptic vesicle proteins, enabling the detection of exocytotic events through the pH change associated with vesicle fusion [12]. Another strategy utilizes circularly permuted fluorescent proteins where neurotransmitter binding alters the protonation state or electrostatic environment of the chromophore, modulating its ICT characteristics and resulting in fluorescence changes [13] [12]. These environmentally sensitive biosensors have been particularly valuable for monitoring glutamatergic transmission, with probes such as iGluSnFR exhibiting robust fluorescence responses to synaptic glutamate release both in vitro and in vivo [13]. The rationetric capability of many ICT-based sensors provides a significant advantage for quantitative imaging in complex tissue environments where probe concentration and path length may vary substantially.

Figure 3: ICT Mechanism. Excitation induces charge separation across the π-system, resulting in redshifted emission sensitive to environmental changes.

Comparative Analysis of Fluorescence Mechanisms

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Fluorescence Mechanisms in Neurotransmitter Sensing

| Parameter | FRET | PET | ICT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Principle | Distance-dependent energy transfer | Electron transfer quenching | Charge redistribution in excited state |

| Distance Dependency | Strong (1-10 nm range) | Weak (through-bond effects) | Minimal (intramolecular) |

| Signal Response | Ratiometric (donor/acceptor ratio) | Fluorescence turn-on/off | Wavelength shift & intensity change |

| Dynamic Range | Moderate to high (ΔF/F ~100-1000%) | High (ΔF/F up to 1000%+) | Moderate (ΔF/F ~50-500%) |

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond to second | Sub-millisecond to second | Millisecond to second |

| Primary Applications | Conformational changes, molecular interactions, protease activity | Ion sensing, small molecule detection | Environmental sensing, rationetric imaging |

| Key Advantages | Ratiometric quantification, well-characterized physics | High sensitivity, excellent signal-to-noise | Environmental sensitivity, rationetric capability |

| Limitations | Requires two fluorophores, spectral crosstalk | Limited to "turn-on" designs, potential background | Moderate specificity, environmental interference |

Table 2: Representative Biosensors Utilizing Different Fluorescence Mechanisms

| Sensor Name | Target | Mechanism | Dynamic Range | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTEN-FRET [15] | PTEN activity | FRET | ~30% ΔR/R | Monitoring PTEN conformational changes in live cells and brain tissue |

| GRABDA [13] | Dopamine | PET (GPCR-based) | ~90% ΔF/F | Real-time dopamine detection in behaving animals |

| iGluSnFR [13] | Glutamate | ICT (cpFP-based) | ~500% ΔF/F | Glutamate release at synapses |

| iAChSnFR [12] | Acetylcholine | ICT (PBP-based) | ~1200% ΔF/F | Cholinergic transmission with high temporal resolution |

| 5-HT sensors [13] | Serotonin | PET/ICT | ~70% ΔF/F | Serotonin dynamics in depression and addiction models |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementation of FRET-Based PTEN Biosensor Using 2pFLIM

Purpose: To monitor PTEN conformational dynamics in live neurons with cellular specificity using FRET-based biosensors and two-photon fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (2pFLIM) [15].

Materials and Reagents:

- PTEN FRET biosensor construct (mEGFP-sREACh tagged)

- Cultured neurons or brain slice preparations

- Appropriate viral vector (AAV, lentivirus) for biosensor delivery

- Two-photon fluorescence lifetime imaging microscope

- Tetrabromobenzotriazole (TBB, CK2 inhibitor)

- Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF)

- Artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF)

Procedure:

- Biosensor Expression: Deliver PTEN FRET biosensor to target neurons using stereotactic viral injection (in vivo) or transfection (in vitro). Allow 2-3 weeks for in vivo expression or 2-3 days for in vitro expression.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare acute brain slices (300-400 μm thickness) from injected animals or use transfected cultured neurons. Maintain samples in oxygenated aCSF at 32°C throughout imaging.

- Microscope Setup: Configure two-photon microscope for fluorescence lifetime imaging using a mode-locked Ti:sapphire laser tuned to 920 nm for mEGFP excitation. Set up time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) module for lifetime measurements.

- Baseline Imaging: Acquire baseline FLIM images at 1-2 frames per minute with 256 × 256 pixel resolution. Collect sufficient photons (>1000 per pixel) for accurate lifetime determination.

- Pharmacological Manipulation:

- Apply CK2 inhibitor TBB (10 μM) to induce PTEN activation. Monitor fluorescence lifetime changes for 20-30 minutes.

- For inhibition studies, apply EGF (100 ng/mL) after TBB washout to suppress PTEN activity.

- Data Analysis:

- Fit fluorescence decay curves to a double-exponential model using appropriate software.

- Calculate average fluorescence lifetime (τ) on a pixel-by-pixel basis.

- Generate lifetime maps and quantify changes in PTEN activity state.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Low expression: Optimize viral titer and promoter selection.

- Poor signal-to-noise: Increase integration time or laser power while avoiding photodamage.

- Motion artifacts: Use thicker agarose embedding for slices or improve head fixation for in vivo preparations.

Protocol 2: Validating PET-Based Neurotransmitter Sensors In Vivo

Purpose: To characterize the performance of PET-based neurotransmitter sensors (e.g., GRAB family) in detecting endogenous neurotransmitter release in behaving animals [13] [12].

Materials and Reagents:

- GRAB sensor construct (e.g., GRABDA, GRABNE, GRAB5HT)

- Sterile artificial CSF for viral delivery

- Fiber optic cannula and ferrule

- Fiber photometry system

- Data acquisition system and behavioral setup

- Appropriate agonists/antagonists for validation

Procedure:

- Sensor Expression: Stereotactically inject AAV encoding GRAB sensor into target brain region (e.g., striatum for DA, hippocampus for NE). Co-inject with cell-type specific promoter if needed.

- Optic Fiber Implantation: Implant fiber optic cannula above injection site during same surgical session or after 2-3 weeks of expression.

- Fiber Photometry Setup: Connect implanted fiber to photometry system with appropriate excitation LEDs (e.g., 470 nm for sensor, 405 nm for isosbestic control) and filtered photodetectors.

- System Calibration: Measure and match light power at fiber tip (typically 10-50 μW). Balance gain for both channels to achieve similar baseline voltage.

- In Vivo Validation:

- Record baseline sensor fluorescence during habituation to testing environment.

- Administer specific receptor agonists (e.g., amphetamine for DA, duloxetine for 5-HT) to evoke neurotransmitter release.

- Apply receptor antagonists (e.g., haloperidol for DA, WAY100635 for 5-HT) to block endogenous transmission.

- Correlate sensor signals with specific behaviors (e.g., reward consumption, social interaction).

- Data Processing:

- Calculate ΔF/F using the formula: (F₄₇₀ - F₄₀₅)/F₄₀₅

- Filter signals (low-pass, 2-10 Hz) to remove noise.

- Align fluorescence traces with behavioral timestamps.

- Perform statistical analysis on peak response amplitudes and kinetics.

Validation Criteria:

- Sensor response should be dose-dependent to pharmacological challenges.

- Responses should be blocked by appropriate receptor antagonists.

- Sensor should show rapid kinetics (rise time <1s) compatible with endogenous transmission.

- Minimal photobleaching during typical recording sessions (30-60 min).

Protocol 3: Rationetric Imaging with ICT-Based Environmental Sensors

Purpose: To perform quantitative neurotransmitter imaging using environmentally sensitive ICT-based probes that exhibit wavelength shifts upon analyte binding [11] [14].

Materials and Reagents:

- ICT-based sensor (e.g., pH-sensitive FP, iGluSnFR variants)

- Widefield or confocal microscope with multi-wavelength capability

- Appropriate filter sets for excitation and emission

- Calibration solutions with known analyte concentrations

- Perfusion system for solution exchange

Procedure:

- Sensor Expression: Express ICT sensor in target cells via transfection or viral transduction. Allow adequate expression time (2-7 days depending on system).

- Microscope Configuration: Set up epifluorescence or confocal microscope with capability for sequential or simultaneous dual-channel imaging. Configure appropriate excitation sources and emission filters matched to sensor spectral properties.

- Calibration Curve Generation:

- Perfuse cells with solutions containing known analyte concentrations (e.g., 0, 1, 10, 100 μM glutamate).

- Acquire images at both emission wavelengths for each concentration.

- Calculate ratio values (R = F₍em₁₎/F₍em₂₎) for each concentration.

- Fit data to appropriate binding equation (e.g., Hill equation) to generate calibration curve.

- Experimental Imaging:

- Acquire time-lapse ratio images at 0.1-1 Hz depending on experimental needs.

- Maintain constant imaging parameters throughout experiment.

- Include controls for photobleaching and autofluorescence.

- Data Analysis:

- Convert ratio values to analyte concentration using calibration curve.

- Perform background subtraction and flat-field correction if needed.

- Analyze spatial and temporal patterns of analyte dynamics.

- Quantify response kinetics (rise time, decay constant).

Advantages of Rationetric Approach:

- Minimizes artifacts from focus drift, sample movement, or variable sensor expression.

- Provides quantitative concentration measurements rather than relative changes.

- Reduces sensitivity to photobleaching during long-term imaging.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Fluorescence-Based Neurotransmitter Sensing

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetically Encoded Sensors | iGluSnFR, GRABDA, iAChSnFR, dLight | Real-time detection of specific neurotransmitters | High specificity, genetic targeting, minimal perturbation |

| Fluorescent Proteins | mEGFP, sREACh, cpGFP, R-GECO | FRET pairs/biosensor components | Photostability, brightness, maturation efficiency |

| Viral Delivery Vectors | AAV-PHP.eB, AAV-retro, Lentivirus | Efficient sensor delivery to specific cell populations | Cell-type specificity, high titer, minimal toxicity |

| Microscopy Systems | Two-photon FLIM, Fiber photometry, Light-sheet microscopy | High-resolution imaging in scattering tissue | Deep penetration, cellular resolution, high speed |

| Pharmacological Tools | TBB (CK2 inhibitor), EGF, receptor agonists/antagonists | System validation and manipulation | Specificity, well-characterized effects, solubility |

The strategic implementation of FRET, PET, and ICT mechanisms in fluorescent biosensor design has dramatically advanced our capability to monitor neurotransmitter dynamics with unprecedented spatial and temporal precision in living systems. Each mechanism offers distinct advantages: FRET provides robust rationetric readouts of conformational changes, PET enables highly sensitive "turn-on" detection of small molecules, and ICT facilitates environmentally sensitive measurements with built-in calibration. The continuing refinement of these photophysical mechanisms, coupled with innovations in protein engineering and imaging technology, promises to yield even more powerful tools for dissecting the complex neurochemical basis of behavior, cognition, and neurological disease. As these biosensors become increasingly sophisticated—offering greater specificity, sensitivity, and multimodal compatibility—they will undoubtedly play a pivotal role in accelerating both fundamental neuroscience discovery and neuropharmaceutical development.

Neurotransmitters form the fundamental chemical language of the brain, governing everything from basic physiological functions to complex cognitive processes [8]. These chemical messengers—including amino acids (glutamate, GABA), monoamines (dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine), acetylcholine, and others—regulate communication across neural circuits through both fast, point-to-point synaptic transmission and slower, diffuse volume transmission [16]. The precise dynamics of these signaling molecules are essential for understanding brain function in health and disease. Imbalances in neurotransmitter systems are implicated in a wide spectrum of neurological and psychiatric disorders, including Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, depression, schizophrenia, and stroke [8] [17]. Consequently, the ability to monitor neurotransmitter dynamics with high spatial and temporal resolution has become a paramount goal in neuroscience research and drug development.

The development of protein-based fluorescent probes represents a transformative advancement in this pursuit, enabling researchers to visualize neurotransmitter activity in real-time with exceptional specificity [16]. Unlike traditional methods such as microdialysis or electrochemical detection, these genetically-encoded tools allow for non-invasive, high-throughput imaging of specific neurotransmitters in genetically-defined cell populations, even in freely behaving animals [16]. This Application Note provides a comprehensive overview of current fluorescent probe technologies for mapping the neurotransmitter landscape, with detailed protocols for their implementation in experimental settings. By framing this information within the context of protein-based probe development, we aim to equip researchers with the practical knowledge needed to advance our understanding of neurochemical signaling in the brain.

The Molecular Toolkit: Fluorescent Probe Design and Mechanisms

Fundamental Design Principles of Protein-Based Fluorescent Probes

Genetically-encoded fluorescent sensors for neurotransmitters typically incorporate two essential molecular components: a recognition element that specifically binds the target neurotransmitter, and a reporting element that transduces this binding event into a measurable optical signal [16]. The recognition element often derives from native neurotransmitter receptors (both ionotropic and metabotropic) or neurotransmitter-binding proteins isolated from bacterial periplasm. The reporting element generally consists of a fluorescent protein or pair of proteins that undergo conformational changes upon ligand binding, resulting in altered fluorescence properties [8] [16].

These probes primarily operate through two distinct optical mechanisms. Single-fluorophore sensors typically utilize circularly permuted fluorescent proteins (cpFP) where the neurotransmitter-binding domain is inserted into the FP backbone. Ligand binding induces conformational changes that directly modulate fluorescence intensity [16]. FRET-based sensors employ two fluorescent proteins that form a Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) pair. Neurotransmitter binding induces a conformational shift that alters the distance or orientation between the donor and acceptor FPs, thereby changing FRET efficiency, which is measured as a ratio metric signal [7].

Advanced Probe Architectures and Recent Innovations

Recent years have witnessed remarkable innovations in probe architecture, significantly expanding the neuroscientist's toolkit. The GRAB (GPCR Activation-Based Sensor) platform has proven particularly versatile, with optimized versions developed for dopamine (GRABDA), serotonin (GRAB5-HT), and norepinephrine (GRABNE) [18]. These sensors leverage naturally high-affinity G protein-coupled receptors as recognition elements, coupled with cpGFP, offering high sensitivity, subsecond kinetics, and exceptional molecular specificity [18] [16].

The iGluSnFR and GABA-SnFR probes represent groundbreaking advances for imaging the brain's primary excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters, respectively [18] [16]. Based on bacterial periplasmic binding proteins rather than eukaryotic receptors, these sensors provide rapid, sensitive detection of glutamate and GABA release with excellent signal-to-noise ratios [16]. Continued optimization has yielded variants with improved targeting to specific subcellular compartments, enabling precise monitoring of synaptic transmission [18].

Table 1: Key Genetically-Encoded Neurotransmitter Sensors and Their Properties

| Sensor Name | Target Neurotransmitter | Scaffold/Design | Dynamic Range (ΔF/F0) | Affinity (Kd) | Kinetics (τON/τOFF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iGluSnFR | Glutamate | GluBP-cpEGFP | 4.5 (in vitro) | 110 μM (in vitro) | ~5 ms/~92 ms |

| SuperGluSnFR | Glutamate | GluBP-CFP/YFP | 0.44 | 2.5 μM | kₒₙ = 3.0 × 10⁷ M⁻¹·s⁻¹ |

| GABA-Snifit | GABA | SNAP-tag FRET | 0.5 | 100 μM | 1.5 s/2.8 s |

| GRABDA | Dopamine | D2R-cpGFP | High (specific values N/A) | 2.5 nM (in vitro) | Subsecond |

| GRAB5-HT | Serotonin | 5-HTR-cpGFP | Improved in new versions | N/A | Subsecond |

| GRABNE | Norepinephrine | α1A-AR-cpGFP | N/A | 20 nM (in vitro) | Subsecond |

| ACh-Snifit | Acetylcholine | SNAP-tag FRET | 0.52 | 20 mM | 2.4 s/4 s |

Experimental Protocols: Implementation and Validation

Protocol: In Vivo Imaging of Dopamine Dynamics Using GRABDA Sensors

Principle: The GRABDA sensor utilizes the human dopamine D2 receptor sequence embedded in a circularly permuted green fluorescent protein (cpGFP). Dopamine binding induces conformational changes that enhance green fluorescence, enabling real-time monitoring of dopamine dynamics in vivo [18].

Materials:

- GRABDA AAV (serotype suitable for target cells, e.g., AAV9 for neuronal expression)

- nVue Imaging System or comparable miniscope [19]

- Stereotaxic injection apparatus

- Fiber optic cannulas (400 μm diameter recommended)

- Inscopix Data Processing Software (IDPS) [19]

Procedure:

- Viral Injection: Anesthetize animal and perform stereotaxic injection of AAV-hSyn-GRABDA into target brain region (e.g., striatum: AP +1.0 mm, ML ±1.8 mm, DV -3.5 mm from bregma for mice).

- Cannula Implantation: Implant gradient-index (GRIN) lens or fiber optic cannula above injection site. Allow 3-4 weeks for viral expression and surgical recovery.

- System Setup: Connect miniscope to cannula and secure to headplate. Ensure proper focus and illumination settings (typical LED power: 0.1-1 mW/mm²).

- Baseline Recording: Record 5-10 minutes of baseline activity in the animal's home cage.

- Stimulus Application: Administer behavioral or pharmacological stimuli (e.g., reward delivery, amphetamine challenge at 2-5 mg/kg i.p.).

- Data Acquisition: Capture video at 20-30 frames per second throughout experimental session.

- Motion Correction: Use IDPS or comparable software to correct for movement artifacts through cross-correlation or feature-based alignment algorithms.

- Signal Extraction: Define regions of interest (ROIs) and extract ΔF/F0 values using the formula: (F - F0)/F0, where F0 represents baseline fluorescence.

Validation: Verify dopamine specificity through pharmacological controls including dopamine receptor antagonists (e.g., haloperidol 0.1 mg/kg) and measurement of response to selective dopamine uptake inhibitors [18].

Protocol: Multiplexed Imaging of Calcium and Neurotransmitter Release

Principle: This protocol enables simultaneous monitoring of neuronal activity (via calcium indicators) and neurotransmitter release (via neurotransmitter sensors) using spectrally distinct probes, allowing correlation of electrical activity with neurochemical output [19].

Materials:

- AAV encoding red-shifted calcium indicator (e.g., jRGECO1a or jYCaMP1)

- AAV encoding green neurotransmitter sensor (e.g., GRABDA for dopamine or iGluSnFR for glutamate)

- Dual-color imaging miniscope (e.g., nVue system) [19]

- Appropriate dichroic mirrors and emission filters for spectral separation

Procedure:

- Viral Preparation: Create mixture of AAVs containing both calcium indicator and neurotransmitter sensor, or inject sequentially with clean period between injections.

- Surgical Preparation: Follow stereotaxic injection and cannula implantation as in Protocol 3.1.

- Optical Configuration: Configure miniscope with appropriate excitation sources (e.g., 565 nm for jRGECO1a, 470 nm for GRABDA) and emission filters to prevent spectral bleed-through.

- Simultaneous Acquisition: Record both channels simultaneously at 20 fps, ensuring precise temporal alignment of signals.

- Data Processing: Process each channel separately for motion correction, then apply image registration to align both channels spatially.

- Correlation Analysis: Calculate cross-correlation between calcium transients and neurotransmitter signals to determine timing relationships.

Technical Considerations: Carefully control expression levels to avoid spectral overlap and potential interactions between sensors. Include controls for possible crosstalk between channels by testing each sensor with the other's excitation wavelength [19].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Neurotransmitter Imaging

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetically-Encoded Sensors | iGluSnFR (glutamate), GRABDA (dopamine), GRAB5-HT (serotonin) | Specific detection of neurotransmitter release in defined cell populations | High molecular specificity, subsecond kinetics, genetic targeting |

| Calcium Indicators | GCaMP series (green), jRGECO series (red) | Monitoring neuronal activity via calcium influx | High sensitivity (ΔF/F0 >5), fast kinetics, multiple colors |

| Viral Delivery Systems | Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) with cell-specific promoters (e.g., hSyn, CaMKIIa) | Targeted sensor expression in specific brain regions and cell types | Specific tropisms, varying expression levels and onset times |

| Imaging Equipment | Miniaturized microscopes (miniscopes), fiber photometry systems | In vivo imaging in freely behaving animals | Lightweight, compatible with behavioral setups, dual-color capability |

| Analysis Software | Inscopix Data Processing Software (IDPS), Suite2p, MATLAB toolboxes | Motion correction, signal extraction, statistical analysis | Automated processing pipelines, ROI detection, noise filtering |

Signaling Pathways and Neurotransmitter Systems

The major neurotransmitter systems in the brain operate through distinct molecular pathways and receptor types, each requiring specialized detection approaches. Understanding these pathways is essential for selecting appropriate probes and interpreting experimental results.

Applications in Disease Models and Drug Development

Protein-based fluorescent probes have enabled significant advances in understanding neurotransmitter dysfunction in disease models, providing insights for therapeutic development.

Neurodegenerative Disorders

In Parkinson's disease models, dopamine sensors have revealed profound alterations in striatal dopamine release dynamics and reuptake mechanisms [8]. GRABDA imaging in animal models has demonstrated abnormal dopamine transients in response to both pharmacological and behavioral stimuli, providing a functional readout for evaluating potential therapeutics. Similarly, in Alzheimer's disease research, glutamate and acetylcholine sensors have uncovered deficits in synaptic transmission and dysregulated neuromodulation that correlate with cognitive decline [8] [16].

Neuropsychiatric Disorders and Stroke

Serotonin sensors (GRAB5-HT) have illuminated the dysregulated serotonin signaling underlying depression and anxiety disorders, enabling evaluation of antidepressant mechanisms beyond simple receptor blockade [18]. In stroke research, novel MRI-based mapping of neurotransmitter pathways has revealed distinct patterns of neurochemical diaschisis, where focal injuries disrupt widespread neurotransmitter systems through both presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms [17]. This approach has identified eight distinct clusters of neurochemical disruption in stroke patients, opening new avenues for targeted neurotransmitter modulation in recovery [17].

Drug Discovery Applications

The high temporal and spatial resolution of these sensors makes them ideal for preclinical drug evaluation. They enable researchers to:

- Measure drug-target engagement in specific brain regions

- Determine the time course of neurotransmitter modulation by candidate compounds

- Identify potential side effects through actions on non-target neurotransmitter systems

- Establish correlation between neurochemical effects and behavioral outcomes

Technical Considerations and Limitations

While protein-based fluorescent probes represent powerful tools for neuroscience research, several important technical considerations must be addressed for proper experimental design and interpretation.

Buffering Effects: All sensors act as buffers for their target neurotransmitters, potentially altering endogenous signaling dynamics, particularly for low-affinity transmitters. This effect can be minimized by using the lowest practical expression levels that still provide adequate signal-to-noise ratio [7].

Kinetic Limitations: Although sensor kinetics continue to improve, most current probes cannot fully resolve the fastest synaptic events, particularly for glutamate at hippocampal synapses where transmitter clearance occurs in sub-millisecond timeframes. Careful selection of probes with appropriate kinetics for the biological question is essential [16].

Spectral Properties and Multiplexing: The limited palette of well-separated fluorescent proteins constrains simultaneous imaging of multiple neurotransmitters. Recent development of red-shifted probes (e.g., rGRABDA) helps address this limitation, enabling dual-color imaging when combined with green indicators [18].

Pharmacological Specificity: While highly specific compared to previous methods, some sensors may show cross-reactivity with structurally similar compounds or metabolites. Appropriate controls, including selective receptor antagonists and measurement of responses in knockout animals, are necessary to validate specificity [16].

The field of protein-based fluorescent probes for neurotransmitter imaging continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising directions emerging. The development of spectrally distinct probes for simultaneous monitoring of multiple neurotransmitters represents a major frontier, as does the creation of sensors with expanded dynamic range and improved signal-to-noise characteristics [18]. Probes with modifiable affinities through optical or pharmacological control would enable researchers to adjust sensitivity for different experimental contexts. Additionally, the integration of these sensors with optogenetic actuators and advanced microscopy techniques will further enhance our ability to dissect complex neurochemical circuits [19].

In conclusion, the expanding toolkit of genetically-encoded fluorescent sensors has fundamentally transformed our ability to monitor neurotransmitter dynamics in the living brain. These tools provide unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution for mapping the neurotransmitter landscape, from fast synaptic signaling of glutamate and GABA to modulatory actions of dopamine, serotonin, and other neuromodulators. As these technologies continue to mature and diversify, they promise to yield deeper insights into both normal brain function and the neurochemical basis of neurological and psychiatric disorders, accelerating the development of novel therapeutic strategies. The protocols and applications outlined in this document provide a foundation for researchers to implement these powerful methods in their investigations of the neurochemical brain.

In the study of complex tissues like the brain, the immense cellular heterogeneity presents a significant challenge. Bulk analysis techniques average signals across countless cell types, obscuring the specific molecular events within functionally distinct populations. Genetic targeting provides a critical solution to this problem by enabling researchers to isolate and investigate specific cell types based on their unique genetic signatures. This approach is particularly transformative for protein-based fluorescent probe research, where understanding cell-type-specific neurotransmitter dynamics, receptor distribution, and signaling pathways is essential for unraveling brain function and dysfunction [8] [20].

The core principle involves leveraging cell-type-specific promoters or Cre-recombinase systems to drive the expression of engineered proteins or probes exclusively in predefined neuronal or glial populations. This specificity is paramount in neurotransmitter imaging research, as different neurotransmitters and neuromodulators are utilized by distinct, often overlapping, neural circuits. Techniques such as the MetRS* system allow for the purification and identification of newly synthesized proteins from specific cellular populations in vivo, dramatically reducing sample complexity and enabling the detection of subtle proteomic changes that would otherwise be lost in whole-tissue analyses [20]. Furthermore, the integration of genetically encoded biosensors, such as the GRAB family of sensors for serotonin and dopamine, with cell-type-specific targeting allows for real-time monitoring of neurotransmitter release with exquisite spatial and temporal resolution in defined neural pathways [18].

Key Methodologies and Experimental Platforms

The MetRS* System for Cell-Type-Specific Proteomics

The Mutant Methionine tRNA Synthetase (MetRS) system is a powerful platform for in vivo labeling, purification, and identification of cell-type-specific proteomes from complex tissues [20]. This method utilizes a genetically engineered mouse line expressing a mutant methionine tRNA synthetase (L274G) that is conditionally activated by Cre recombinase. The MetRS incorporates the non-canonical amino acid analog azidonorleucine (ANL) into newly synthesized proteins, which can then be selectively isolated from heterogeneous tissue samples.

Key Experimental Protocol for MetRS* [20]:

In Vivo Metabolic Labeling with ANL:

- Drinking Water Administration: Dissolve ANL (up to 1% wt/vol) and maltose (0.7% wt/vol) in the animals' drinking water. Provide this solution to Cre-positive MetRS* mice and their controls for a period of typically 2-3 weeks, monitoring daily intake.

- Intraperitoneal Injection: Alternatively, dissolve ANL in a physiological buffer (e.g., 400 mM in NaCl solution) and administer via daily intraperitoneal injections (10 mL/kg body weight) for a shorter period, such as one week.

Tissue Harvesting and Protein Extraction:

- Dissect the tissue region of interest and homogenize it in a lysis buffer (e.g., PBS with 1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, Benzonase, and protease inhibitors).

- Denature the homogenate by heating to 75°C for 15 minutes, then centrifuge to collect the supernatant.

- Measure and adjust protein concentrations across all samples to ensure consistency (optimal range: 2-4 μg/μL).

Click Chemistry and Protein Purification:

- Perform a copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition ("click" reaction) to covalently link the ANL-labeled proteins (containing the azide group) to alkyne-bearing agarose beads.

- After extensive washing to remove non-specifically bound proteins, the captured, cell-type-specific proteins are eluted for downstream analysis by mass spectrometry or Western blot.

Table 1: Key Reagents for the MetRS* Protocol [20]

| Reagent | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ANL (Azidonorleucine) | Non-canonical amino acid incorporated by MetRS* into newly synthesized proteins. | Can be administered via drinking water or IP injection; pH may need adjustment. |

| MetRS* (L274G) Mouse Line | Genetically engineered model expressing mutant tRNA synthetase in a Cre-dependent manner. | Requires crossing with appropriate Cre-driver line for cell-type specificity. |

| Alkyne-Agarose Beads | Solid support for covalent capture of ANL-labeled proteins via click chemistry. | Essential for purifying labeled proteins from complex tissue lysates. |

| Click Chemistry Reagents | Catalyzes the reaction between the ANL azide group and the alkyne on the beads. | Typically a copper-based catalyst system. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents proteolytic degradation of proteins during extraction and purification. | Should be added to all buffers immediately before use. |

Genetically Encoded Fluorescent and Bioluminescent Sensors

A rapidly expanding toolkit of genetically encoded sensors allows for the real-time visualization of neurotransmitter dynamics, calcium signaling, and other physiological processes in specific cell types [18]. These sensors are typically engineered from natural receptor proteins or other ligand-binding domains fused to fluorescent protein reporters.

Notable Sensor Platforms [18]:

- GRAB Sensors (GPCR-Activation-Based Sensors): These include high-sensitivity green and red sensors for neurotransmitters like dopamine (GRABDA), serotonin (GRAB5HT), and norepinephrine. They exhibit rapid kinetics and high specificity, enabling the monitoring of neurotransmitter release in vivo during behavior.

- iGluSnFR: A genetically encoded sensor for glutamate, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter. Improved variants offer higher signal-to-noise ratios and can be targeted to postsynaptic sites for imaging synaptic transmission.

- OxLight1: A sensor for orexin neuropeptides, validated in mice during various behaviors using fiber photometry and two-photon imaging.

- GCaMP: The most widely used family of genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs). When expressed in specific cell types, GCaMP allows researchers to infer neural activity based on calcium transients associated with action potentials.

- StayGold: A recently developed green fluorescent protein with exceptional photostability, enabling extended time-lapse imaging of cellular structures and protein trafficking with minimal photobleaching.

Table 2: Selected Genetically Encoded Sensors for Neuroimaging [18]

| Sensor Name | Target | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRABDA / GRAB5HT | Dopamine / Serotonin | High sensitivity, fast kinetics, multiple colors available | Real-time monitoring of neuromodulator release in vivo |

| iGluSnFR | Glutamate | Synaptically targeted variants available | Imaging of synaptic transmission in circuits |

| GCaMP | Calcium Ions | High dynamic range, multiple generations optimized | Large-scale recording of neural activity in defined cell types |

| OxLight1 | Orexin | Validated for fiber photometry & 2P imaging | Monitoring of neuropeptide dynamics during behavior |

| mScarlet3 | N/A (Fluorescent Tag) | Bright, photostable, fast-maturing red fluorescent protein | Protein fusion tagging for long-term, high-resolution imaging |

Experimental Workflow and Data Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a generalized conceptual workflow for conducting a cell-type-specific study using genetic targeting, from initial design to data interpretation.

Conceptual Workflow for Genetic Targeting Studies

The specific experimental workflow for the MetRS* system detailed in this protocol is shown below, highlighting the key steps from animal preparation to proteomic identification.

MetRS* Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of genetic targeting strategies requires a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table outlines essential components for building these experimental pipelines.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Targeting

| Category / Reagent | Specific Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Model Organisms | MetRS* Mouse Line [20] | Enables Cre-dependent, cell-type-specific protein labeling for proteomic studies. |

| Cre-Driver Mouse/Rat Lines | Provides genetic access to specific cell types (e.g., CamKIIa for excitatory neurons). | |

| Cell-Type-Specific Sensors | GRAB Sensor AAVs [18] | Genetically encoded reporters for real-time imaging of neurotransmitter dynamics in vivo. |

| GCaMP AAVs [18] | Indicators for monitoring calcium activity as a proxy for neural firing in specific cells. | |

| Protein Labeling Reagents | ANL (Azidonorleucine) [20] | Methionine analog incorporated into newly synthesized proteins in MetRS* cells. |

| Alkyne-Agarose Beads [20] | Solid-phase resin for bioorthogonal capture of ANL-labeled proteins via click chemistry. | |

| Advanced Fluorophores | StayGold Protein [18] | Exceptionally photostable fluorescent protein for long-duration imaging. |

| mScarlet3 [18] | Bright, fast-maturing red fluorescent protein for fusion tags and multiplexing. |

Genetic targeting is no longer a niche technique but a fundamental prerequisite for rigorous research in complex tissues. By enabling precise access to defined cellular populations, methodologies like the MetRS* system for proteomics and genetically encoded sensors for functional imaging are driving a paradigm shift in neuroscience. They empower researchers to move beyond descriptive correlations to a mechanistic understanding of how specific cell types contribute to circuit function, behavior, and disease pathology through their unique protein expression and neurotransmitter signaling profiles. The continued development and dissemination of these tools, coupled with the detailed protocols for their application, are critical for accelerating discovery in neurotransmitter research and drug development.

From Bench to Brain: Methodological Applications in Disease Research and Drug Discovery

Circuit dysfunction in neuropsychiatric disorders arises from complex alterations in neurotransmitter dynamics. Understanding these changes requires precise tools to visualize and quantify signaling events within the brain. Protein-based fluorescent probes have revolutionized this field by enabling real-time monitoring of neurotransmitter release, reuptake, and receptor activation in live cells and intact neural circuits. These genetically encoded biosensors provide unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution for investigating the neurochemical basis of depression and addiction, allowing researchers to bridge the gap between molecular signaling and circuit-level dysfunction. This Application Notes and Protocols document provides a comprehensive framework for applying these advanced imaging tools to study neurotransmitter dynamics in established disease models, with detailed protocols for probe selection, experimental implementation, and data analysis.

Probe Selection and Validation for Targeted Neurotransmitter Systems

Table 1: Fluorescent Probes for Key Neurotransmitter Systems in Depression and Addiction Research

| Neurotransmitter | Probe Name/Type | Detection Mechanism | Key Applications | Kinetics/ Sensitivity | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine (DA) | GRABDA sensors [18] | GPCR activation | Monitoring dopaminergic activity in reward pathways [18] | High signal-to-noise; in vivo compatible [18] | Test in ventral tegmental area, striatum [21] |

| Serotonin (5-HT) | iSeroSnFR [18] | Serotonin-binding protein | Serotonin release dynamics [18] | Optimized for in vivo imaging [18] | Validate in dorsal raphe projections [22] |

| Serotonin (5-HT) | PYR-C3-CIT [23] | SERT-binding conjugate | Serotonin transporter visualization [23] | Large Stokes shift (>135nm) [23] | Acute brain slice imaging; SERT localization [23] |

| Norepinephrine (NE) | GRABNE sensors [18] | GPCR activation | Noradrenergic signaling in stress pathways [18] | Red and green variants available [18] | Locus coeruleus projections; stress models [24] |

| Glutamate | iGluSnFR variants [18] | Glu-binding protein | Glutamatergic transmission [18] | Improved SNR and targeting [18] | Cortical and hippocampal circuits [7] |

| Calcium (Ca²⁺) | GCaMP series [7] | Ca²⁺-induced conformation change | Neuronal activity mapping [7] | Varying Kd values (0.15-0.56 μM) [7] | Correlate with neurotransmitter release [7] |

| Voltage | ASAP4 [18] | Voltage-sensitive domain | Electrical activity monitoring [18] | Extended recording capability [18] | Simultaneous with neurotransmitter detection [18] |

The selection of appropriate fluorescent probes must align with the specific research questions and model systems. For depression research, focusing on serotonin and norepinephrine sensors is critical given their established roles in mood regulation and stress response [22]. For addiction models, dopamine sensors are essential for investigating reward pathway dysregulation [21]. Multi-modal approaches combining neurotransmitter sensors with calcium or voltage indicators enable correlation of neurochemical signaling with neuronal activity, providing a more comprehensive understanding of circuit dysfunction [18].

Probe validation should include specificity tests, determination of expression patterns, and verification of appropriate kinetics for the biological process being studied. For instance, the novel PyrAte-based SERT probes offer exceptional photostability and large Stokes shifts, enabling multiplexed imaging with other markers [23]. Similarly, next-generation GRAB sensors provide improved signal-to-noise ratios for detecting subtle neurotransmitter fluctuations in disease models [18].

Experimental Models for Depression and Addiction Research

Table 2: Animal Models and Behavioral Paradigms for Circuit Dysfunction Studies

| Disorder | Animal Model | Induction Method | Key Behavioral Tests | Circuit Focus | Neurotransmitter Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Chronic stress model [24] | Repeated restraint/social defeat [24] | Forced swim test, Sucrose preference [24] | Prefrontal cortex-hippocampus-amygdala [22] | Serotonin, norepinephrine in DRN, LC [22] |

| Depression | Genetic model [24] | Dusp6 downregulation (female-specific) [22] | Splash test, Social interaction [24] | Corticolimbic circuits [22] | Altered stress response signaling [22] |

| Addiction | Self-administration [21] | Operant drug delivery [21] | Relapse tests, Progressive ratio [21] | Mesolimbic dopamine pathway [21] | Dopamine in NAc, VTA [21] |

| Addiction | Behavioral sensitization [21] | Repeated non-contingent drug exposure [21] | Locomotor activity monitoring [21] | Corticostriatal circuits [21] | Glutamate, dopamine plasticity [21] |

| Comorbidity | Dual pathology model | Stress + drug exposure | Integrated test batteries | Prefrontal-accumbens pathway | Monoamine and glutamate dysregulation |

Animal models of depression typically involve chronic stress paradigms that elicit behavioral manifestations such as anhedonia (measured by sucrose preference test) and despair (measured by forced swim test) [24]. These models demonstrate face validity through similarity to human symptoms, construct validity through shared neurobiological mechanisms, and predictive validity through response to antidepressant treatments [24]. Addiction models focus on drug self-administration and behavioral sensitization, capturing different aspects of addictive processes [21]. The self-administration model particularly demonstrates strong face validity as animals voluntarily perform tasks to receive drug rewards, mimicking human drug-seeking behavior [21].