HPA Axis Dysregulation and Neuroendocrine Interactions: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Interventions in Stress Pathophysiology

This comprehensive review synthesizes current research on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis as the central regulator of the stress response and its complex interactions with other neuroendocrine systems.

HPA Axis Dysregulation and Neuroendocrine Interactions: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Interventions in Stress Pathophysiology

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes current research on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis as the central regulator of the stress response and its complex interactions with other neuroendocrine systems. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the article explores foundational HPA axis physiology, developmental programming, and cross-system communication with reproductive, immune, and gut-brain pathways. It examines methodological approaches for investigating HPA axis function, analyzes mechanisms of stress-induced dysregulation across physiological systems, and evaluates comparative interactions with parallel neuroendocrine axes. The review highlights emerging therapeutic targets and translational applications for disorders linked to HPA axis dysfunction, including autoimmune, metabolic, psychiatric, and reproductive conditions.

Core Architecture and System Integration of the Neuroendocrine Stress Response

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis serves as the body's primary neuroendocrine system for maintaining homeostasis in the face of real or perceived challenges. This sophisticated axis coordinates adaptive responses to physical, psychological, and immunological stressors through a cascade of hormonal signals culminating in glucocorticoid secretion. Within the broader context of stress research, understanding the HPA axis's intricate architecture and regulatory mechanisms is paramount for elucidating the pathophysiological basis of numerous stress-related disorders and developing novel therapeutic interventions. The HPA axis represents a critical interface between the nervous and endocrine systems, translating neural signals into hormonal outputs that regulate diverse physiological processes including metabolism, immune function, cardiovascular tone, and behavior [1] [2]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of HPA axis anatomy, physiology, and research methodologies, with particular emphasis on the pivotal role of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) in initiating and modulating the stress response.

Anatomical Architecture of the HPA Axis

The Paraventricular Nucleus (PVN): Central Command

The hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) serves as the prime regulator of the HPA axis, housing the neurosecretory neurons that initiate the stress response cascade. The PVN contains three functionally distinct neuronal populations:

- Parvocellular neurosecretory neurons: These CRH-producing neurons project to the median eminence and constitute the primary drivers of the HPA axis [3]

- Magnocellular neurosecretory neurons: These primarily produce oxytocin and vasopressin and project to the posterior pituitary [3]

- Long-projecting neurons: These regulate autonomic function through projections to the brainstem and spinal cord [3]

The development and differentiation of PVN neurons are governed by specific transcription factors. Brn-2 is essential for terminal differentiation of both parvocellular and magnocellular neurons, while Otp and Sim1 regulate the maturation of neurosecretory neurons expressing CRH, AVP, TRH, and oxytocin [3]. Sim1 knockout mice demonstrate severe reductions in CRH, AVP, and OT neurons and rarely survive to adulthood, highlighting this factor's critical role in PVN development [3].

Pituitary Gland: The Relay Center

The pituitary gland consists of two embryologically and functionally distinct components:

- Adenohypophysis (anterior pituitary): Derived from Rathke's pouch, this structure contains specialized hormone-producing cells including corticotropes that synthesize and secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) [3]

- Neurohypophysis (posterior pituitary): Originating from the ventral diencephalon, this region stores and releases oxytocin and vasopressin produced by PVN and supraoptic nucleus (SON) magnocellular neurons [3]

Corticotropes in the anterior pituitary express receptors for CRH and AVP, allowing them to respond to hypothalamic signals by releasing ACTH into the systemic circulation.

Adrenal Cortex: Glucocorticoid Production

The adrenal cortex represents the final endocrine component of the HPA axis. Upon stimulation by ACTH, the zona fasciculata of the adrenal cortex synthesizes and secretes glucocorticoids (cortisol in humans, corticosterone in rodents). ACTH binds to melanocortin 2 receptors (MC2R), activating adenylate cyclase and increasing intracellular cAMP levels [1]. This signaling cascade enhances cholesterol transport into mitochondria via the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein, which represents the rate-limiting step in glucocorticoid synthesis [1].

Table 1: Major Components of the HPA Axis

| Anatomical Structure | Key Cell Types | Secreted Factors | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paraventricular Nucleus (PVN) | Parvocellular neurosecretory neurons | CRH, AVP | Initiate HPA axis activation; regulate ACTH secretion |

| Anterior Pituitary | Corticotropes | ACTH | Stimulate glucocorticoid production in adrenal cortex |

| Adrenal Cortex | Zona fasciculata cells | Glucocorticoids (cortisol/corticosterone) | Mediate widespread metabolic and immune effects |

Physiological Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The Neuroendocrine Cascade

HPA axis activation follows a sequential hormonal cascade initiated at the level of the PVN:

- CRH and AVP Release: Parvocellular neurons secrete corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and arginine vasopressin (AVP) into the hypophysial portal system at the median eminence [4]

- ACTH Secretion: CRH and AVP travel to the anterior pituitary where they act synergistically on corticotropes. CRH binds to CRH-R1 receptors, activating adenylate cyclase and increasing cAMP production, while AVP binds to V1b receptors, activating protein kinase C [1] [4]

- Glucocorticoid Production: ACTH stimulates the adrenal cortex to synthesize and secrete glucocorticoids, which exert widespread effects on energy metabolism, immune function, and neural activity [1]

CRH functions as the principal ACTH secretagogue, as evidenced by studies demonstrating that CRH knockout mice show severely impaired basal and stress-induced ACTH release [1]. AVP alone has minimal effect on ACTH secretion but potently synergizes with CRH to amplify corticotrope response [4].

Neurotransmitter Regulation of PVN Activity

The PVN receives extensive innervation from multiple brain regions that convey information about various stressors. These inputs release neurotransmitters that precisely regulate the activity of CRH neurons:

- Excitatory inputs: Glutamate, norepinephrine, and serotonin typically increase CRH neuronal excitability [5]

- Inhibitory inputs: GABA represents the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter regulating PVN activity [5]

Additional modulators include dopamine, acetylcholine, and various neuropeptides that fine-tune the stress response [5]. This complex innervation allows for integration of diverse sensory and interoceptive signals that collectively determine HPA axis output.

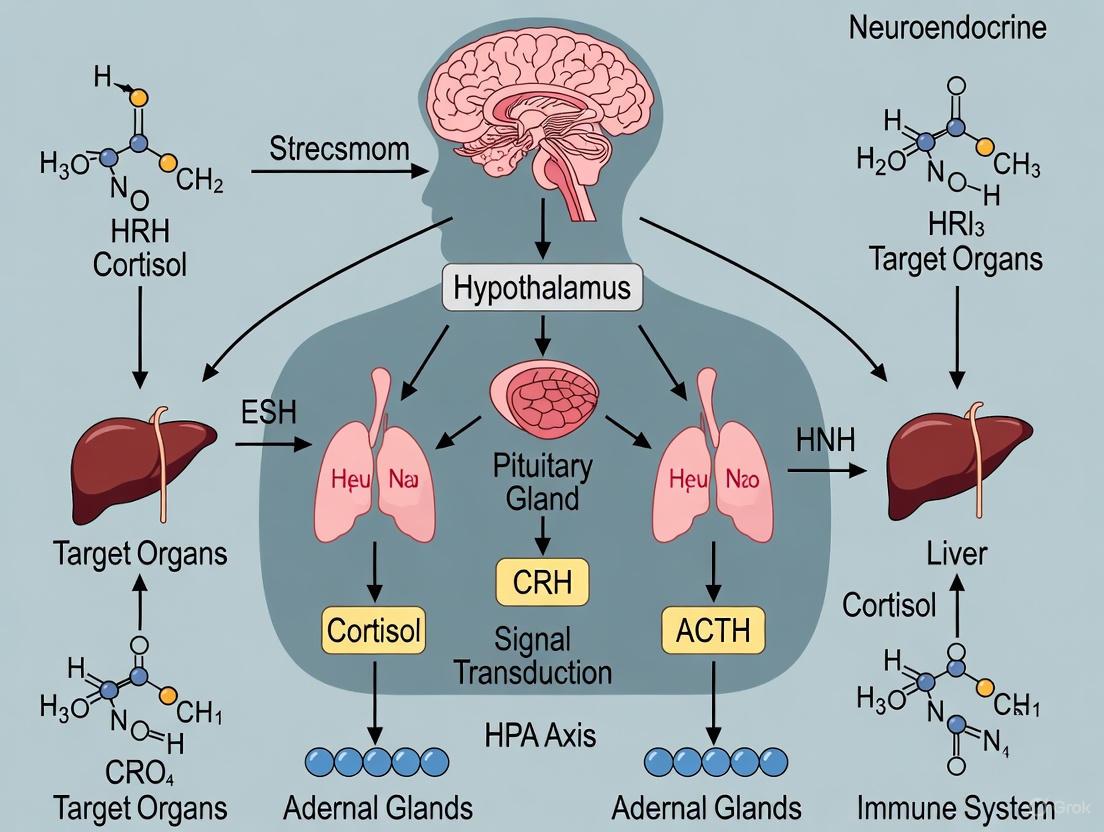

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway of the HPA axis and its regulatory inputs:

Figure 1: Core HPA Axis Signaling Pathway. This diagram illustrates the sequential activation of the HPA axis from hypothalamic PVN to systemic cortisol release, including negative feedback mechanisms that regulate the stress response.

Circadian Regulation and Stress Response Patterns

The HPA axis demonstrates a pronounced circadian rhythm independent of stress exposure. Under basal conditions, glucocorticoid secretion follows a diurnal pattern with peak levels occurring during the active phase (morning in humans, evening in rodents) [2]. This circadian variation is regulated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which provides synaptic input to the PVN and helps synchronize HPA activity with the light-dark cycle [2].

Stress-induced HPA activation follows distinct patterns depending on stressor characteristics:

- Reactive responses: Direct homeostatic challenges (e.g., physical threat, immune activation) typically engage brainstem noradrenergic pathways that directly stimulate PVN neurons [1]

- Anticipatory responses: Psychological stressors activate oligosynaptic pathways originating in limbic structures (e.g., hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, amygdala) that modulate PVN activity largely through disinhibition mechanisms [1]

The magnitude and duration of HPA activation vary according to stressor intensity, controllability, predictability, and novelty [2].

Regulatory Mechanisms and Feedback Loops

Glucocorticoid Receptor Signaling and Negative Feedback

Glucocorticoids exert potent negative feedback on the HPA axis at multiple levels to limit the duration and magnitude of stress responses. This feedback occurs through three temporal domains:

- Fast feedback: Occurs within minutes, mediated by non-genomic glucocorticoid actions likely involving membrane-associated receptors [4]

- Intermediate feedback: Involves glucocorticoid modulation of post-translational processing and release of pre-formed peptides [2]

- Slow feedback: Occurs over hours to days and involves genomic actions mediated by cytosolic glucocorticoid receptors (GR) that alter gene transcription [1]

At the PVN, fast feedback inhibition of CRH neurons is mediated by glucocorticoid-dependent mobilization of endocannabinoids, which act as retrograde messengers to suppress presynaptic glutamate release via CB1 receptors [4]. Additional feedback sites include the pituitary gland, where glucocorticoids inhibit ACTH synthesis and secretion, and higher brain centers such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, which provide inhibitory input to the PVN [1].

Heterosynaptic Modulation in the PVN

The PVN exhibits sophisticated heterosynaptic modulation wherein one neurotransmitter system alters the efficacy of another in regulating CRH neuronal activity. This occurs through both presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms:

- Presynaptic heterosynaptic modulation: Involves alteration of neurotransmitter release from terminals, often through actions on presynaptic receptors [5]

- Postsynaptic heterosynaptic modulation: Occurs when a neurotransmitter modifies the postsynaptic response to another neurotransmitter, frequently through signal transduction pathways that regulate receptor sensitivity or membrane excitability [5]

For example, norepinephrine can enhance GABAergic transmission onto CRH neurons via α1-adrenoceptors, while serotonin inhibits GABA release through 5-HT1A receptors [5]. This heterosynaptic integration allows for sophisticated computation of diverse stress-related signals within the PVN microcircuitry.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Assessment of HPA Axis Function

Research investigating HPA axis physiology employs diverse methodological approaches across multiple levels of analysis:

Table 2: Experimental Methods for HPA Axis Investigation

| Analysis Level | Technical Approaches | Measured Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular | RT-PCR, in situ hybridization, Western blot, ELISA | CRH/AVP mRNA and protein, receptor expression, glucocorticoid levels |

| Neuroanatomical | Immunohistochemistry, tract tracing, electron microscopy | Neuronal activation (c-Fos), connectivity, synaptic ultrastructure |

| Physiological | Radioimmunoassay, HPLC, microdialysis | Hormone levels, neurotransmitter release, heart rate, blood pressure |

| Functional | Pharmacological challenges, electrophysiology, optogenetics | Neuronal excitability, hormone responses to stimuli, feedback sensitivity |

Chronic Stress Paradigms

Studies investigating maladaptive HPA axis regulation frequently employ chronic stress models including:

- Chronic variable stress: Exposure to unpredictable stressors over days to weeks [4]

- Chronic social defeat: Repeated exposure to aggressive conspecifics [1]

- Restraint/immobilization stress: Repeated physical confinement [6]

These paradigms produce neuroplastic adaptations including increased CRH and AVP expression in the PVN, enhanced excitatory innervation of CRH neurons, reduced GABAergic inhibition, and diminished glucocorticoid feedback efficacy [4]. The following diagram illustrates a typical experimental workflow for investigating HPA axis function in rodent models:

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for HPA Axis Research. This diagram outlines a comprehensive approach to investigating HPA axis function in preclinical models, integrating molecular and physiological analyses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HPA Axis Investigation

| Reagent/Chemical | Specific Example | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRH-R1 Antagonist | NBI-27914 | Selective blockade of CRH type 1 receptors to investigate CRH signaling [6] |

| Adrenergic Receptor Ligands | Prazosin (α1-antagonist), propranolol (β-antagonist) | Dissection of catecholaminergic influences on PVN neuronal activity [5] |

| GABA Receptor Modulators | Bicuculline (GABA-A antagonist), baclofen (GABA-B agonist) | Investigation of inhibitory control of CRH neurons [6] [5] |

| Glucocorticoid Receptor Agonists/Antagonists | RU28362 (GR agonist), RU486 (GR antagonist) | Assessment of glucocorticoid feedback mechanisms [1] |

| Corticosterone/Cortisol Assays | ELISA, RIA kits | Quantification of circulating glucocorticoid levels [6] |

| Neuroanatomical Tracers | Fluorogold, cholera toxin B | Mapping of afferent and efferent connections of PVN neurons [4] |

Pathophysiological Implications and Research Applications

Dysregulation of the HPA axis represents a central feature in numerous pathological conditions:

- Neuropsychiatric disorders: Depression, PTSD, and anxiety disorders are associated with altered HPA axis activity, including CRH hypersecretion, glucocorticoid resistance, and impaired negative feedback [7] [8]

- Autoimmune diseases: Chronic stress-induced HPA dysfunction can promote inflammatory responses and contribute to conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and multiple sclerosis [7]

- Metabolic disorders: Prolonged glucocorticoid excess promotes hepatic glycogenolysis, lipolysis, and insulin resistance, contributing to metabolic syndrome [7]

- Neurodegenerative disorders: Chronic glucocorticoid exposure can damage hippocampal neurons and impair cognitive function [8]

Recent research has identified pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) as an important regulator of stress responses, with specific gene polymorphisms in the ADCYAP1 gene associated with PTSD vulnerability, particularly in women [9] [10]. This discovery highlights the potential for targeting novel neuropeptide systems in the development of future stress-related therapeutics.

The intricate organization and regulation of the HPA axis underscores its fundamental role in maintaining physiological homeostasis amid changing environmental demands. Continued investigation of PVN circuitry, neuropeptide signaling, and glucocorticoid receptor function will undoubtedly yield critical insights for developing targeted interventions for the myriad disorders associated with HPA axis dysregulation.

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis posits that environmental exposures during sensitive developmental windows program physiological systems, influencing lifelong disease susceptibility [11]. At its core, this hypothesis suggests that early-life adaptations enhance short-term survival but may increase the risk of chronic diseases over decades [11]. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a central stress response and homeostatic system, is one of the key fetal systems most sensitive to these programming effects [11] [12]. Prenatal programming of the fetal HPA axis is proposed as a primary mechanism linking early experiences to later disease risk [12]. During gestation, the developing fetal brain exhibits remarkable plasticity, making it highly susceptible to maternal, placental, and other intrauterine signals [12]. If these signals indicate conditions of deprivation or stress, the fetus adjusts its developmental trajectory, potentially at a cost to long-term health, especially if a mismatch occurs between the predicted and actual postnatal environment [12].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Developmental Programming of the HPA Axis

| Concept | Description | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Plasticity | Ability of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes in response to environmental conditions [11]. | Allows for adaptive calibration of HPA axis set-points to the anticipated environment. |

| Critical Window | A specific developmental period during which the system is most susceptible to programming influences [12]. | Explains the time-sensitive nature of HPA axis programming by early-life exposures. |

| Fetal Programming | The process by which an environmental stimulus during a sensitive developmental period has a lasting impact on the structure and function of organ systems [12]. | Provides a mechanistic link between the prenatal environment and adult health. |

| Mismatch Hypothesis | The concept that disease risk arises when the prenatally predicted environment differs from the actual postnatal environment [12]. | Explains why early adaptive changes can become maladaptive later in life. |

HPA Axis Physiology and Development

The Functional HPA Axis

The mature HPA axis is a neuroendocrine system that regulates the body's physiological and psychological adaptation to stress. Its activation involves a coordinated cascade: in response to a stressor, the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus secretes corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and arginine vasopressin (AVP) into the hypophyseal portal system [11] [13] [12]. These hormones stimulate the anterior pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn prompts the adrenal cortex to secrete the glucocorticoid cortisol into the systemic circulation [11] [13] [12]. Circulating cortisol exerts widespread effects, including on metabolism, immune function, and cognition, and primarily regulates its own secretion through a negative feedback loop by binding to glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) in the hippocampus, hypothalamus, and pituitary to inhibit further CRH and ACTH release [13] [12].

HPA Axis Signaling Pathway

Developmental Timeline of the HPA Axis

The construction of the HPA axis is an intricate process that begins early in fetal life. The hypothalamus derives from the anteroventral neuroectoderm, with key transcription factors like Brn-2, Otp, and Sim1 regulating the differentiation of CRH-producing neurons in the PVN [3]. The pituitary gland develops from a dual origin—the oral ectoderm forms Rathke's pouch (anterior pituitary), while the neural ectoderm gives rise to the posterior pituitary [3]. The fetal adrenal cortex is distinct, featuring a large fetal zone that produces precursor steroids; this zone involutes after birth, and the adult adrenal architecture with its three distinct zones—zona glomerulosa, zona fasciculata, and zona reticularis—matures postnatally, with the zona reticularis becoming fully formed around adrenarche [14]. The fetal HPA axis does not develop in isolation but is part of an integrated maternal-placental-fetal (MPF) unit [12]. The human placenta produces CRH identical to hypothalamic CRH, and unlike the negative feedback in the mature brain, maternal cortisol stimulates placental CRH production, creating a unique positive feedback loop that drives a substantial increase in maternal and fetal glucocorticoid levels over gestation [12].

Table 2: Critical Windows in Human HPA Axis Development

| Developmental Stage | Key Developmental Events | Vulnerability to Programming |

|---|---|---|

| First Trimester | Hypothalamic primordium differentiation; pituitary gland formation; placental CRH production begins [3] [12]. | Foundation for entire stress axis is laid; exposure to synthetic glucocorticoids or extreme maternal stress can disrupt initial organization. |

| Second Trimester | Prolific neurogenesis and neuronal migration; establishment of basic HPA circuitry [12]. | System is highly plastic; maternal nutrition and stress can influence neuronal connectivity and receptor density. |

| Third Trimester | Exponential rise in placental CRH; maturation of negative feedback mechanisms; fetal zone of adrenal is active [12]. | High glucocorticoid exposure can program the set-point for stress sensitivity and feedback efficiency. |

| Early Postnatal Period | Involution of fetal adrenal zone; establishment of adult adrenal zonation; refinement of feedback loops [14]. | The postnatal environment can reinforce or counteract prenatal programming; caregiver interaction is critical. |

Mechanisms of Developmental Programming

Pathways of Prenatal Influence

The fetal HPA axis can be programmed by several maternal and placental factors, with glucocorticoids acting as a final common pathway. The primary mechanisms include:

- Maternal Glucocorticoid Exposure: Maternal stress, whether physiological or psychological, can lead to elevated maternal cortisol. This cortisol can cross the placenta and access the fetal circulation, potentially altering the development of fetal brain structures involved in HPA regulation, such as the hippocampus, amygdala, and PVN [11] [12]. The enzyme 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11β-HSD2), which acts as a placental barrier by inactivating cortisol, can be downregulated by maternal stress or malnutrition, further increasing fetal exposure [11].

- Placental CRH Drive: The placenta, by producing ever-increasing amounts of CRH throughout gestation, is a major driver of the maternal and fetal steroidogenic environment [12]. Elevated placental CRH has been linked to preterm birth and may precondition the fetal HPA axis to be more reactive after birth.

- Epigenetic Modifications: Early-life exposures can induce stable changes in gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. For instance, maternal diet (e.g., choline intake) and stress have been shown to alter the DNA methylation status of genes encoding the glucocorticoid receptor and 11β-HSD2, thereby changing their expression levels and influencing HPA axis function long-term [11].

Key Programming Exposures and Experimental Evidence

Research has identified specific maternal exposures that consistently lead to HPA axis programming in offspring.

- Maternal Nutrition: Animal models consistently show that maternal protein or caloric restriction elevates basal HPA tone and the dynamic stress response in offspring, often via changes in central glucocorticoid receptor expression [11]. Human studies, such as those on the Dutch Hunger Winter, have shown that prenatal undernutrition is associated with altered HPA axis reactivity in offspring six decades later [11].

- Mental Health and Chronic Stress: Maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy are associated with higher placental CRH levels and have been linked to altered cortisol responses in infants and children [12]. Chronic stress can lead to a dysregulated HPA axis characterized by impaired negative feedback.

- Maternal Obesity and Metabolic State: Maternal obesity and high maternal lipid levels have been associated with increased cortisol reactivity in children, suggesting that the metabolic environment can also program the stress axis [11].

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating HPA Axis Programming

Human Study Designs and Protocols

Prospective longitudinal cohort studies are the gold standard for investigating HPA axis programming in humans. The general workflow involves recruiting pregnant women, extensively characterizing their prenatal environment, and then following their offspring from birth into adulthood to assess HPA axis function at multiple time points.

HPA Programming Research Workflow

Detailed Protocol for a Longitudinal Birth Cohort Study:

Prenatal Assessment (During each trimester):

- Maternal Questionnaires: Administer validated instruments to assess psychological stress (e.g., Perceived Stress Scale), anxiety (e.g., State-Trait Anxiety Inventory), diet (e.g., food frequency questionnaires), and lifestyle factors.

- Maternal Biological Sampling: Collect maternal saliva, blood, and/or urine.

- Salivary Cortisol: Participants collect saliva at home at specified times (e.g., upon waking, 30 minutes post-waking, before lunch, before bed) over 1-2 days to assess diurnal cortisol rhythm [12].

- Plasma/Serum: Analyze for placental CRH, ACTH, cortisol, and inflammatory markers. Samples are typically processed within 2 hours and stored at -80°C.

- Urine: Assess for catecholamines as a measure of sympathetic activity.

Neonatal Assessment (At Birth):

- Placental Collection: Immediately after delivery, collect placental tissue biopsies from standardized locations (e.g., central cotyledon, free membranes). Flash-freeze a portion in liquid nitrogen for RNA/protein analysis (e.g., CRH gene expression, 11β-HSD2 activity) and preserve another portion in formalin for histology.

- Cord Blood Collection: Collect umbilical cord blood from the umbilical vein. Process to obtain plasma/serum and analyze for cortisol, ACTH, and CRH levels.

Postnatal HPA Axis Assessment in Offspring (e.g., at 6, 12, 24 months):

- Diurnal Cortisol: Parents collect child's saliva at specified times (e.g., waking, pre-nap, post-nap, bedtime) on 1-2 days.

- Stress Reactivity Protocols: Conduct mild, standardized laboratory stressor tests suitable for the age group.

- Infants: The "Still-Face Paradigm," where the parent interacts normally, then maintains a neutral still face for 2 minutes, before resuming normal interaction. Saliva is collected pre-, immediately post-, and 20-minutes post-stressor to measure cortisol response [12].

- Older Children/Adults: The Trier Social Stress Test for Children (TSST-C), which involves a public speaking and mental arithmetic task in front of an audience. Saliva or blood is collected at baseline, immediately post-task, and at multiple recovery timepoints (e.g., +10, +20, +30, +45 mins) to model the cortisol response curve, including peak response and recovery slope [11] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HPA Axis Programming Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH), Antibodies | To detect and quantify CRH protein or mRNA expression in placental or brain tissue. | Immunohistochemistry on placental sections; ELISA for plasma CRH; qPCR for CRH mRNA. |

| Cortisol ELISA/EIA Kits | To measure cortisol concentration in biological fluids (saliva, serum, plasma, urine). | Quantifying diurnal cortisol profiles and stress-induced cortisol responses in maternal and offspring samples. |

| ACTH Chemiluminescence Immunoassay | To measure ACTH levels in plasma, requiring careful sample handling due to peptide instability. | Assessing pituitary response in the HPA axis cascade, often in conjunction with cortisol measures. |

| DNA Methylation Analysis Kits (e.g., Bisulfite Conversion) | To prepare DNA for analysis of epigenetic modifications, such as methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) promoter. | Investigating epigenetic mechanisms by which prenatal stress programs the offspring HPA axis. |

| RNA Extraction Kits & qPCR Reagents | To isolate and quantify gene expression levels of HPA axis components (e.g., GR, MR, CRH, POMC). | Analyzing gene expression in post-mortem brain tissue (animal models) or peripheral blood cells. |

| 11β-HSD2 Activity Assay | To measure the enzymatic activity that converts active cortisol to inactive cortisone. | Determining the placental barrier capacity to glucocorticoids using placental tissue homogenates. |

| Validated Psychometric Scales | Standardized questionnaires to quantify psychological constructs. | Assessing maternal prenatal stress, anxiety, and depression levels (e.g., PSS, STAI). |

Lifelong Consequences of HPA Axis Programming

The maladaptive programming of the HPA axis is a significant risk factor for a spectrum of disorders across the lifespan. The consequences are not limited to mental health but encompass physical health domains as well.

- Neuropsychiatric Disorders: HPA axis hyperactivity and impaired negative feedback are well-documented in Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) [15]. Programmed hypercortisolemia can lead to neuronal damage and atrophy in brain regions rich in GR receptors, such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, which are critical for mood regulation [15]. Similar mechanisms are implicated in anxiety disorders and schizophrenia [3].

- Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases: Chronic stress leads to HPA axis dysregulation, characterized by impaired feedback, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, and paradoxical cortisol output, which fosters a pro-inflammatory state [7]. This immune imbalance weakens protective mechanisms and shifts the immune response toward autoimmunity, with evidence linking persistent HPA dysfunction to diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and multiple sclerosis [7].

- Cardiometabolic Diseases: Programming that results in elevated cortisol can promote the development of hypertension, obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome through cortisol's effects on appetite, fat deposition, glucose metabolism, and vascular function [11] [13] [12].

The evidence is compelling that the HPA axis is a key facilitator of the link between early-life adversity and adult disease. Understanding the mechanisms of developmental programming, including the critical windows and the role of the maternal-placental-fetal unit, provides powerful insights for preventive medicine. Future research should focus on multi-omics approaches to integrate genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data from longitudinal cohorts, which will help delineate precise biomarkers of risk and resilience [7]. A major unanswered question is the reversibility of HPA alterations, prompting investigation into interventions—ranging from nutritional supplements and probiotics to psychological support for mothers—that could attenuate the lifelong effects of adverse developmental programming [11] [7]. Ultimately, identifying individuals with programmed HPA axis dysregulation early in life could allow for targeted interventions to improve long-term health trajectories.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis represents a primary neuroendocrine system governing the physiological response to stress, integrating neural and hormonal signals to maintain homeostasis under challenging conditions. This sophisticated circuitry coordinates adaptive behavioral and physiological responses through the precise regulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), arginine vasopressin (AVP), and glucocorticoids. The HPA axis operates as a coordinated functional system wherein CRH and AVP are frequently secreted together and closely cooperate in regulating stress responses, blood pressure, metabolism, and behavior [16]. The fundamental importance of this system is evident in its requirement for stress adaptation and survival, though its dysregulation contributes significantly to numerous pathological conditions spanning psychiatric, metabolic, cardiovascular, and immune disorders [1] [17].

At its core, the HPA axis functions as a neuroendocrine cascade wherein corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) serves as the principal hypothalamic regulator under basal conditions and in response to most acute stressors [18]. CRH, a 41-amino acid peptide produced primarily in the parvocellular neurons of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus, is released into the pituitary portal system upon stress exposure [19]. It stimulates adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion from anterior pituitary corticotrophs through activation of CRH receptor type 1 (CRHR1), a G-protein-coupled membrane receptor [18]. Arginine vasopressin (AVP), co-expressed in many CRH neurons, acts synergistically with CRH to potentiate ACTH release, primarily through V1b receptors [16] [18]. This coordinated peptide signaling ensures robust ACTH secretion, which subsequently stimulates glucocorticoid production (cortisol in humans, corticosterone in rodents) from the adrenal cortex [1].

Table 1: Core Components of the HPA Axis Neuroendocrine Circuitry

| Component | Primary Site of Synthesis | Key Receptors | Major Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRH | Parvocellular PVN neurons | CRHR1 | Principal stimulator of ACTH secretion; coordinates behavioral stress response |

| AVP | Parvocellular PVN neurons (co-localized with CRH) | V1b | Potentiates CRH-induced ACTH release; important for sustained stress response |

| ACTH | Anterior pituitary corticotrophs | MC2R (adrenal) | Stimulates glucocorticoid synthesis and secretion from adrenal cortex |

| Glucocorticoids | Adrenal cortex | GR, MR | Metabolic adaptation, immune modulation, negative feedback on HPA axis |

The critical regulatory feature of the HPA axis is the glucocorticoid-mediated negative feedback system, wherein elevated circulating glucocorticoids act at multiple levels (hippocampus, hypothalamus, pituitary) to suppress further CRH and ACTH release, thus limiting the stress response and preventing excessive activation [1] [18]. This feedback occurs through two primary corticosteroid receptors: the high-affinity mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) and the lower-affinity glucocorticoid receptor (GR) [18]. The balance between these regulatory components determines HPA axis set-point and stress responsiveness, with dysregulation contributing to hypercortisolemia associated with numerous stress-related diseases and age-related pathology [18].

Molecular Signaling Pathways and Mechanisms

Genomic and Non-genomic Signaling Mechanisms

The signaling pathways governing CRH, AVP, and glucocorticoid interactions operate across multiple temporal domains through both genomic and non-genomic mechanisms. Glucocorticoid signaling is mediated through genomic and non-genomic receptors located in cellular membranes and intracellular compartments [16]. The genomic effects involve corticosteroid receptors belonging to the nuclear receptor superfamily of transcription factors that modulate transcriptional processes through direct binding to glucocorticoid response elements (GRE) or mineralocorticoid response elements (MRE) in DNA [16]. The GR is a 97 kDA protein encoded by the NR3C1/Nr3c1 gene that cooperates with several co-regulators, including steroid receptor coactivators (SRCs) [16].

The CRH gene promoter regulation involves complex interactions with glucocorticoids and cAMP pathways. The human CRH promoter does not contain a consensus glucocorticoid regulatory element (GRE), but does possess a negative GRE (nGRE) that mediates, in part, the inhibition of CRH promoter activity by glucocorticoids [20]. Additionally, cAMP stimulates the CRH promoter through both the consensus cAMP response element (CRE) and a previously unrecognized caudal type homeobox response element (CDXRE) [20]. Glucocorticoid-mediated repression of cAMP-stimulated CRH promoter activity involves interactions between the CRE and the upstream nGRE, demonstrating the intricate cross-talk between these signaling pathways [20].

Table 2: Key Signaling Pathways in HPA Axis Regulation

| Signaling Pathway | Key Elements | Biological Effect | Time Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRH/CRHR1 | Gαs-coupled, adenylate cyclase, cAMP, PKA | Stimulates POMC transcription and ACTH secretion | Rapid (seconds to minutes) |

| AVP/V1b | Gαq-coupled, phospholipase C, IP3, DAG, PKC | Potentiates CRH effects on ACTH release | Rapid (seconds to minutes) |

| Glucocorticoid Genomic | GR/MR, GRE/MRE, transcriptional regulation | Negative feedback; metabolic and immune programming | Slow (hours to days) |

| Glucocorticoid Non-genomic | Membrane receptors, second messengers | Rapid feedback inhibition | Rapid (seconds to minutes) |

| cAMP-CRH Promoter | CRE, CDXRE, nGRE, AP-1 proteins | Regulates CRH gene expression | Intermediate (hours) |

The cellular excitability of corticotrophs is dynamically regulated through these signaling pathways. Corticotrophs are electrically excitable and fire both spontaneous single-spike action potentials and secretagogue-induced bursting activity, with bursting resulting in greater increases in intracellular calcium and enhanced ACTH secretion [21]. Large-conductance calcium- and voltage-activated potassium (BK) channels are key regulators of this bursting behavior [21]. Glucocorticoids modulate corticotroph excitability through both BK-dependent and BK-independent mechanisms, with pretreatment with 100 nM corticosterone reducing spontaneous activity and preventing the transition from spiking to bursting after CRH/AVP stimulation [21]. This demonstrates how glucocorticoids fine-tune pituitary responsiveness through regulation of electrical activity patterns.

Pathway Integration and Cross-Talk

The integration of CRH, AVP, and glucocorticoid signaling occurs through complex cross-talk mechanisms at multiple levels. Vasopressin interacts with the HPA axis at various levels—in hypothalamic nuclei affecting CRH release, in the pituitary gland enhancing ACTH release, and in the adrenal glands modulating steroid hormone action [16]. These interactions are facilitated by positive and negative feedback between specific components of the HPA system with engagement of other neurotransmitting and neuropeptidergic pathways [16]. Importantly, the cooperation between AVP and steroid hormones may be affected by cellular stress combined with hypoxia, and by metabolic, cardiovascular, and respiratory disorders [16].

The glucocorticoid feedback mechanism plays an essential role in regulating CRH production and limiting stress responses. The central sensors for this feedback are MR and GR receptors expressed in the brain and pituitary corticotrophs [18]. GRs are distributed throughout the brain but are most concentrated in hypothalamic neurons and corticotrophs, while MRs are present in the hypothalamus and most abundant in the hippocampus [18]. This receptor distribution creates a tiered feedback system wherein MRs primarily regulate basal HPA tone, while GRs mediate stress-induced feedback, allowing for precise control of HPA axis activity across varying conditions.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Electrophysiological Assessment of Corticotroph Activity

The electrophysiological properties of corticotrophs can be investigated using sophisticated techniques including perforated patch-clamp recordings and dynamic clamp technology. In one comprehensive approach, corticotroph cells are acutely isolated from male mice (aged 2-5 months) constitutively expressing green fluorescent protein under the control of the proopiomelanocortin promoter, allowing for specific identification of corticotrophs [21]. Cells are cultured on coverslips in serum-free media and recordings are obtained 24-96 hours after isolation using the perforated patch mode of the whole-cell patch clamp technique with amphotericin B [21].

For electrophysiological recordings, the standard bath solution contains (in mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 0.1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4, 300 mOsmol/L). The standard pipette solution contains (in mM): 10 NaCl, 30 KCl, 60 K2SO4, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, and 50 sucrose (pH 7.2, 290 mOsmol/L) [21]. Recordings are performed at room temperature to facilitate stable recordings, with patch pipettes fabricated from borosilicate glass with resistances typically between 2-3 MΩ. A gravity-driven perfusion system is used to apply drugs with a flow rate of 1-2 mL/min to minimize flow-induced artifacts [21].

The dynamic clamp technique provides a powerful method to investigate the role of specific ion channels in regulating electrical activity. This technique allows investigators to add or subtract specific ionic currents in real-time during electrophysiological recordings. In corticotroph studies, researchers have used dynamic clamp to demonstrate that CRH-induced bursting can be switched to spiking by subtracting a fast BK current, whereas addition of a fast BK current can induce bursting in corticosterone-treated cells [21]. This approach has been instrumental in establishing that glucocorticoids modulate corticotroph excitability through both BK-dependent and BK-independent mechanisms.

Molecular and Genetic Approaches

Promoter analysis techniques have been essential for elucidating the molecular mechanisms governing CRH gene regulation. Studies utilizing the mouse corticotroph cell line AtT20 have revealed complex interactions between glucocorticoids and cAMP in regulating CRH promoter activity [20]. Experimental approaches include subcloning CRH 5'-flanking DNA sequence into promoterless luciferase reporter vectors, creating serial 5' deletions of the CRH promoter region, and introducing specific point mutations to identify functional response elements [20].

For CRH promoter studies, the human CRH genomic clone is subcloned into promoterless Photinus (firefly) luciferase reporter vectors [20]. Transient transfections are performed using calcium phosphate precipitation in AtT20 cells, with cotransfection with a Renilla luciferase expression vector to serve as an internal control for transfection efficiency [20]. Cells are typically treated with test substances for 6-8 hours before lysis and luciferase activity measurement using dual-luciferase assays. This approach has identified that cAMP stimulates the CRH promoter through both the consensus CRE and a novel CDXRE, while glucocorticoid-mediated inhibition involves interactions between the CRE and an upstream nGRE [20].

Genetic mouse models have provided significant insights into HPA axis function. Corticotroph-specific BK channel knockout mice (BK−/−) have revealed that glucocorticoids can inhibit excitability through BK-independent mechanisms to control spike frequency [21]. Similarly, CRF knockout mice show impaired adrenal responses to various acute stressors, confirming CRH's critical role in stress-induced ACTH release [19]. These genetic approaches, combined with electrophysiological and molecular techniques, provide a comprehensive toolkit for dissecting the neuroendocrine circuitry governing stress responses.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HPA Axis Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Models | AtT20 mouse corticotroph cell line | CRH promoter analysis; regulation of POMC expression | In vitro studies of gene regulation [20] |

| Animal Models | CRF knockout mice; BK-POMC-GFP mice | Genetic dissection of HPA axis components | Electrophysiology, stress response testing [21] [19] |

| Peptides/Reagents | CRH, AVP, Corticosterone, Dexamethasone | Receptor activation; stress axis modulation | In vitro and in vivo HPA axis challenge studies [21] [20] |

| Promoter Constructs | CRH-luciferase reporters (CRH-663, CRH-433, etc.) | Analysis of promoter regulation and response elements | Luciferase reporter assays [20] |

| Electrophysiology | Amphotericin B, Dynamic clamp systems | Corticotroph electrical activity recording | Perforated patch-clamp recordings [21] |

Visualization of Neuroendocrine Circuitry

Core HPA Axis Signaling Pathway

Figure 1: Core HPA Axis Signaling and Feedback Pathways. This diagram illustrates the integrated neuroendocrine circuitry involving CRH, AVP, and glucocorticoid signaling. The pathway initiates with stressor detection, leading to CRH and AVP co-release from paraventricular nucleus neurons into the pituitary portal system. These peptides stimulate ACTH secretion from anterior pituitary corticotrophs, which subsequently drives glucocorticoid production from the adrenal cortex. Glucocorticoids complete the circuit through negative feedback mediated by GR and MR receptors at multiple levels, including the hypothalamus and pituitary.

Cellular Signaling and Feedback Mechanisms

Figure 2: Cellular Signaling and Regulatory Mechanisms. This diagram details the intracellular signaling pathways in corticotrophs, highlighting the convergence of CRH and AVP signaling on cAMP production, leading to POMC transcription and ACTH secretion through PKA and CREB activation. Glucocorticoid feedback occurs through genomic mechanisms via GR and MR receptors, as well as non-genomic modulation of BK channels that regulate electrical activity patterns. The BK channel regulation represents a key mechanism whereby glucocorticoids fine-tune corticotroph responsiveness.

The intricate neuroendocrine circuitry involving CRH, AVP, and glucocorticoid signaling represents a sophisticated system for maintaining homeostasis under stress conditions. The functional coordination between these components operates as an integrated AVP-HPA system, with vasopressin interacting with the HPA axis at multiple levels through regulation of CRH release, ACTH secretion, and steroid hormone action [16]. Understanding these interactions at molecular, cellular, and systems levels provides crucial insights for developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting stress-related disorders.

The translational implications of this research are substantial, given that dysregulation of the HPA axis contributes to numerous pathological conditions including depression, anxiety, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular diseases [16] [17]. Emerging evidence suggests that central and peripheral interactions between AVP and steroid hormones are reprogrammed in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, with these rearrangements exerting either beneficial or harmful effects depending on context [16]. Furthermore, the demonstration that glucocorticoids modulate corticotroph excitability through both BK-dependent and BK-independent mechanisms reveals potential targets for therapeutic intervention [21].

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the tissue-specific regulation of these signaling pathways, particularly given evidence that glucocorticoids can exert stimulatory or inhibitory effects on CRH gene expression depending on cellular context [20]. Additionally, greater understanding of how these neuroendocrine circuits are reprogrammed in disease states may yield novel approaches for restoring homeostasis. The continued development of sophisticated experimental approaches, including dynamic clamp electrophysiology, genetic models, and promoter analysis techniques, will be essential for advancing our understanding of this critical neuroendocrine circuitry and its implications for human health and disease.

{c#introduction}

Cross-Talk with the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) Axis: Stress-Reproduction Interfaces

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is the body's central neuroendocrine system for responding to stress, culminating in the release of cortisol. In parallel, the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis is the primary regulator of reproductive function, governing the secretion of sex steroids such as testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone. These two systems do not operate in isolation; they engage in a complex, bidirectional crosstalk that is crucial for maintaining homeostasis. Activation of the HPA axis, particularly when chronic, can significantly suppress the reproductive axis. This interface, often described as a stress-reproduction interface, represents a critical adaptive mechanism where the body prioritizes survival over reproductive investment during challenging conditions. Understanding the physiological basis of this interaction, the experimental methods for its study, and the resulting molecular pathways is fundamental to research in stress neuroendocrinology and has profound implications for drug development in areas of stress-related reproductive disorders and infertility [22] [23] [24].

Physiological Basis of HPA-HPG Axes Interaction

The crosstalk between the stress and reproductive axes occurs at multiple levels, from the central nervous system to the peripheral gonads, through hormonal, neural, and intracellular signaling pathways.

Central Neuroendocrine Suppression

At the central level, the primary point of interaction is the suppression of the HPG axis's master regulator, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). The stress-induced release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus directly inhibits the pulsatile secretion of GnRH from hypothalamic neurons [25] [24]. This suppression is further mediated by the elevated levels of glucocorticoids (e.g., cortisol) that result from HPA axis activation. Reduced GnRH pulsatility leads to diminished release of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the anterior pituitary, which in turn results in suppressed gonadal steroidogenesis and ovulation or spermatogenesis [23] [25]. Furthermore, kisspeptin, a potent stimulator of GnRH neurons, is also suppressed by stress and glucocorticoids, providing another critical pathway for central reproductive inhibition [24].

Peripheral and Molecular Pathways

Beyond the brain, significant interactions occur at the gonadal level. Glucocorticoid receptors are expressed in the ovaries and testes, and high cortisol levels can directly blunt gonadal response to LH and FSH, inhibiting the production of sex steroids like estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone [23]. A key molecular phenomenon is the "cortisol steal" or pregnenolone steal, where the shared precursor, pregnenolone, is shunted away from the synthesis of sex steroids towards the increased production of cortisol in the adrenal cortex under chronic stress, leading to a relative deficiency in progesterone and other downstream reproductive hormones [25].

The autonomic nervous system provides another interface. Stress activates the sympathetic nervous system, which directly innervates the ovaries. Norepinephrine release from these sympathetic terminals can alter follicular development and steroidogenesis, and chronic activation is implicated in conditions like polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) [23]. Finally, the gut-brain axis contributes to this interplay; stress-induced dysbiosis and increased gut permeability can lead to systemic inflammation, which further exacerbates HPA axis dysregulation and negatively impacts reproductive tissues, influencing conditions like endometriosis and PCOS [15] [25].

Experimental Evidence and Research Data

The theoretical framework of HPA-HPG crosstalk is supported by a body of experimental evidence from both animal and human studies, which also reveals a nuanced picture depending on the nature and duration of the stressor.

Table 1: Summary of Key Experimental Findings on Stress-HPG Axis Interactions

| Study Type / Model | Key Experimental Findings | Implications for HPG Function |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic Stress (Animal Models) [23] [24] | Inhibition of GnRH pulsatility; reduced LH/FSH secretion; decreased testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone; suppression of kisspeptin. | Leads to impaired fertility, disrupted estrous cycles, anovulation, and poor reproductive outcomes. |

| Acute Psychosocial Stress (Human Experimental) [26] | Meta-analysis of 21 studies (N=881) shows a stimulatory effect on testosterone, progesterone, and estradiol levels in response to acute laboratory stressors. | Suggests acute stress may transiently stimulate, not inhibit, HPG activity in humans, highlighting a key difference from chronic stress effects. |

| Maternal Separation (Rat Model) [23] | Produced sexually dimorphic effects on reproductive behavior; longer mount/latency times in males, altered maternal programming of reproductive strategy in females. | Early-life stress programs adult sexual behavior and HPG axis set-points via epigenetic and organizational mechanisms. |

| Sympathetic Denervation (Rat Ovarian) [23] | Inhibition of follicular growth following ovarian denervation; norepinephrine facilitates follicular development. | Demonstrates a critical role for direct sympathetic neural input in regulating ovarian function outside classic HPA axis. |

Methodological Protocols for Key Findings

The evidence summarized in Table 1 is derived from rigorous experimental protocols. A standard method for investigating acute stress in humans is the use of standardized acute laboratory stressors, such as the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST). This protocol typically involves a brief preparation period followed by a mock job interview and mental arithmetic task in front of an audience. Saliva or blood samples are collected at baseline, immediately post-stress, and at several time points during recovery (e.g., +10, +20, +30, +60 mins) to measure the dynamic response of gonadal steroids (testosterone, estradiol, progesterone) and cortisol [26].

In animal models, the Maternal Separation (MS) protocol is a classic early-life stress paradigm. In rodents, pups are separated from the dam for periods of 3-8 hours per day during the first two postnatal weeks. Control litters are either left completely undisturbed or subjected to brief handling. The long-term effects on reproductive physiology and behavior, including lordosis quotient, mount latency, and hormone receptor expression in the brain (e.g., ERα in the hypothalamus), are then assessed in adulthood [23].

To elucidate the role of direct sympathetic input to the gonads, the superior ovarian nerve denervation model is used. In rats or mice, this involves surgical transection or chemical ablation of the nerves in the suspensory ligament that innervate the ovary. The functional outcomes, such as follicular development, steroid hormone output, and the incidence of cystic structures, are compared between denervated and sham-operated control animals [23].

Signaling Pathways and Neuroendocrine Circuits

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core signaling pathways and neuroendocrine circuits that mediate the crosstalk between the stress and reproductive axes.

Diagram 1: Central & Peripheral HPA-HPG Cross-Talk

(Central & Peripheral HPA-HPG Cross-Talk)

Diagram 2: Experimental Stress-Reproduction Workflow

(Experimental Stress-Reproduction Workflow)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

To effectively investigate the HPA-HPG axis crosstalk, researchers rely on a suite of specific reagents, assays, and molecular tools. The following table details key resources essential for experiments in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HPA-HPG Axis Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH) | Used to directly stimulate the HPA axis in vivo or in vitro to study downstream effects on HPG function. | Often administered intracerebroventricularly (ICV) in animal models; specific agonists/antagonists (e.g., CRH type 1 receptor antagonists) are used for mechanistic studies. |

| Kisspeptin Agonists/Antagonists | To probe the role of the kisspeptin system in mediating stress effects on GnRH neurons. | e.g., kisspeptin-10 (KP-10) as an agonist; peptide antagonists like p271 used to block kisspeptin receptor (KISS1R) signaling [24]. |

| Enzyme Immunoassays (EIA) & Radioimmunoassays (RIA) | For the precise quantification of hormone levels in serum, plasma, saliva, and tissue culture media. | Widely used for measuring Cortisol, ACTH, Testosterone, Estradiol, Progesterone, LH, and FSH. |

| Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR) Antagonists | To block glucocorticoid signaling and isolate its specific effects in the crosstalk mechanism. | e.g., Mifepristone (RU-486); used in vivo or in cell culture to determine GR-dependent pathways. |

| qPCR Assays & Antibodies for IHC | For molecular analysis of gene and protein expression in neural and reproductive tissues. | Target genes: CRH, AVP, GnRH, Kiss1, POMC, steroidogenic enzymes (e.g., CYP19A1). Antibodies for localization of proteins like ERα, GR, CRH receptors [23]. |

| Stereotaxic Surgery Equipment | For precise cannulation and microinjection of reagents into specific brain nuclei in rodent models. | Used to target the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), arcuate nucleus (where kisspeptin neurons reside), or median eminence. |

The intricate cross-talk between the HPA and HPG axes is a cornerstone of the body's adaptive response to environmental challenges, ensuring that resources are allocated towards survival at the potential cost of immediate reproductive investment. The mechanistic insights, derived from both animal and human studies, reveal a multi-layered interaction involving central neuroendocrine suppression, peripheral gonadal effects, and autonomic nervous system involvement. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of these pathways—including the roles of CRH, glucocorticoids, kisspeptin, and sympathetic signaling—is paramount. Future therapeutic strategies for stress-induced reproductive dysfunction may hinge on targeted interventions that reset this critical neuroendocrine dialogue, whether through novel small molecules, neuromodulation, or lifestyle interventions that address the root causes of HPA axis dysregulation.

The gut-brain axis represents one of the most significant paradigms in modern neurobiology, forming a complex, bidirectional communication network that integrates gastrointestinal function with central nervous system activity. Within this framework, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis—the body's primary neuroendocrine stress response system—engages in continuous crosstalk with the gut microbiota. This interaction is mediated through multiple signaling pathways including neural, endocrine, immune, and metabolic routes [27]. The microbial ecosystem inhabiting the gastrointestinal tract, comprising approximately 100 trillion microorganisms, possesses a genetic potential that vastly exceeds the human genome, positioning it as a powerful environmental factor capable of influencing host physiology and stress responsiveness throughout the lifespan [28] [29].

Understanding the mechanistic basis of microbiota-HPA axis interactions is crucial for stress research and therapeutic development. Evidence from germ-free (GF) animal models demonstrates that the absence of gut microbiota leads to altered stress responses, neurotransmitter levels, and neurodevelopment, which can be partially restored through microbial colonization [30]. Furthermore, clinical observations reveal that disorders such as depression and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) frequently present with concurrent dysregulation of both the HPA axis and gut microbiota, suggesting a shared pathophysiology [28]. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence on the communication pathways between gut microbiota and HPA function, with emphasis on mechanistic insights, experimental approaches, and implications for neuroendocrine-related disorders.

Core Communication Pathways in the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis

The microbiota-gut-brain axis (MGBA) operates through an integrated network of parallel communication pathways that enable bidirectional information flow between gut microbes and the brain. These pathways collectively regulate HPA axis activity through distinct but interconnected mechanisms.

Neural Pathways

The vagus nerve serves as the most direct neural connection between the gut and brain, with various receptors on vagal afferents sensing and transmitting signals from the gut to the brain [31]. This nerve affects CNS reward neurons and influences mood and behavior [31]. Additionally, the enteric nervous system (ENS) forms a complex intrinsic neural network within the gastrointestinal wall that communicates with the CNS through intestinofugal neurons and vagal afferent pathways [32] [31]. Microbial metabolites including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and neurotransmitters can directly stimulate these neural pathways to modulate brain function and HPA axis activity [33].

Endocrine and Neuroendocrine Pathways

The HPA axis itself functions as a central neuroendocrine pathway within the MGBA. In response to stress, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), which triggers pituitary secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), ultimately stimulating glucocorticoid (cortisol in humans, corticosterone in rodents) release from the adrenal cortex [28]. Gut microbes can influence this cascade through multiple mechanisms, including the production of neuroactive compounds (GABA, serotonin, dopamine) and modulation of gut hormones that circulate to affect brain function [27] [33]. Additionally, glucocorticoids can directly influence gut microbiota composition by altering gut transit time, intestinal permeability, and nutrient availability [29].

Immune and Inflammatory Pathways

The immune system serves as a critical intermediary in gut-brain communication. Gut microbes regulate the development and function of both mucosal and systemic immunity through metabolites such as SCFAs, tryptophan derivatives, and secondary bile acids [30]. Microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) including lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and peptidoglycan can translocate across compromised intestinal barriers and activate pattern recognition receptors (e.g., Toll-like receptors), triggering neuroinflammatory responses that modulate HPA activity [28] [30]. Proinflammatory cytokines and prostaglandins generated through these mechanisms represent potent activators of the HPA axis [28].

Metabolic Pathways

Gut microbiota produce a diverse array of microbial metabolites that systemically influence host physiology. Short-chain fatty acids (butyrate, acetate, propionate) derived from dietary fiber fermentation demonstrate particularly wide-ranging effects, serving as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) ligands, and modulators of neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier integrity [34] [33]. Other microbial metabolites including bile acids, tryptophan catabolites, and neurotransmitters additionally contribute to the metabolic regulation of HPA function [27] [30].

Table 1: Primary Communication Pathways in the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis

| Pathway | Key Components | Mechanism of HPA Axis Modulation |

|---|---|---|

| Neural | Vagus nerve, Enteric Nervous System (ENS) | Direct neural signaling from gut to brain; microbial metabolites activate vagal afferents [27] [31] |

| Endocrine/Neuroendocrine | HPA axis, Gut hormones, Microbial neurotransmitters | Glucocorticoid feedback; microbial production of neuroactive compounds (GABA, serotonin, dopamine) [27] [33] |

| Immune | Cytokines, MAMPs (LPS, peptidoglycan), TLRs | Immune activation and neuroinflammation; proinflammatory cytokines as HPA activators [28] [30] |

| Metabolic | SCFAs, Bile acids, Tryptophan metabolites | Epigenetic regulation (HDAC inhibition); receptor activation (GPCRs); barrier integrity modulation [34] [30] |

Figure 1: Multidirectional Communication Pathways Linking Gut Microbiota to HPA Axis Function

Key Microbial Metabolites Regulating HPA Activity

Gut microbiota produce a diverse array of bioactive metabolites that systemically influence host physiology, with several demonstrating significant effects on HPA axis regulation. These microbial-derived compounds function through distinct molecular mechanisms to modulate neuroendocrine stress responses.

Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

Butyrate, acetate, and propionate represent the most extensively studied microbially-derived metabolites with HPA-modulating properties. These SCFAs are produced primarily through bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber in the colon and exhibit multiple mechanisms of action [33]. Butyrate in particular functions as a potent histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, enabling epigenetic regulation of gene expression in stress-responsive brain regions [34] [33]. SCFAs also activate G-protein coupled receptors (GPR41, GPR43, GPR109a) expressed on enteroendocrine cells, immune cells, and peripheral neurons, influencing inflammatory pathways and neurotransmitter release [30]. Additionally, SCFAs contribute to maintenance of intestinal barrier integrity and blood-brain barrier function, indirectly modulating HPA axis activity by limiting translocation of inflammatory mediators [31]. Under acute stress conditions, SCFA levels are frequently reduced, associated with increased inflammation, gut permeability, and alterations in brain function and mood [34].

Neuroactive Metabolites and Neurotransmitters

Gut microbiota significantly influence central neurotransmitter systems through direct production and precursor modulation. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS, is produced by various bacterial species including Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium [34] [33]. Similarly, catecholamines (dopamine, norepinephrine) are produced by Escherichia, Bacillus, and Proteus species, with levels increasing during acute stress to mediate physiological stress responses [34]. Perhaps most significantly, gut microbiota regulate serotonin biosynthesis, with approximately 90% of the body's serotonin produced by enterochromaffin cells in response to microbial metabolites [33]. Tryptophan availability—the precursor to serotonin—is directly influenced by gut microbes, with acute stress reducing tryptophan levels and shifting metabolism toward the kynurenine pathway, resulting in neuroactive metabolites that influence mood and cognition [34].

Immune-Active Microbial Molecules

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, represents a potent activator of inflammatory signaling that can influence HPA axis activity. Under conditions of increased intestinal permeability, LPS translocates into systemic circulation and triggers immune activation through Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), leading to production of proinflammatory cytokines that stimulate HPA activity [28]. Similarly, bacterial peptidoglycan can translocate into the brain and activate pattern recognition receptors (Nod1), influencing brain development and behavior [28]. These microbial-associated molecular patterns establish a direct link between gut microbiota composition, immune activation, and neuroendocrine function.

Table 2: Key Microbial Metabolites Regulating HPA Axis Function

| Metabolite | Producing Bacteria | Mechanism of Action | Impact on HPA Axis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butyrate | Faecalibacterium, Ruminococcus, Lactobacillus | HDAC inhibition; GPCR activation; barrier integrity [34] [33] | Reduced under acute stress; anti-inflammatory; epigenetic regulation [34] |

| GABA | Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides | Primary inhibitory neurotransmitter; reduced neuronal excitability [34] [33] | Promotes relaxation; reduced stress responsivity; alterations linked to anxiety [34] |

| Serotonin | Precursor regulation by Bacteroides, Clostridium, Enterococcus [34] | Tryptophan metabolism; mood, sleep, emotional regulation [33] | 90% gut-derived; reduced during stress; impacts mood and gut motility [34] [33] |

| Catecholamines | Escherichia, Bacillus, Proteus [34] | Dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine synthesis; reward, motivation, alertness [34] [33] | Increased during acute stress; mediates physiological stress responses (heart rate, blood pressure) [34] |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia, Bacteroides) [28] | TLR4 activation; proinflammatory cytokine production; immune activation [28] [30] | Potent HPA activator; linked to neuroinflammation and stress susceptibility [28] |

Experimental Models and Methodological Approaches

Research investigating microbiota-HPA axis interactions employs a diverse array of experimental models and methodological approaches, each offering distinct advantages for elucidating specific aspects of this complex relationship.

Germ-Free Animal Models

Germ-free (GF) mice, raised in completely sterile isolators without any microorganisms, represent a foundational model for investigating microbiota-HPA axis interactions. These animals exhibit significant alterations in HPA axis function, including exaggerated corticosterone responses to acute stress compared to conventionally colonized counterparts [28] [30]. The HPA axis hyperactivity observed in GF mice can be normalized by microbial colonization early in life, but not in adulthood, highlighting the importance of critical developmental windows for microbiota-HPA programming [28]. GF models additionally demonstrate immune system abnormalities, including underdeveloped mucosal lymphoid structures, reduced secretory immune factors, and decreased numbers of immune cells, which collectively contribute to altered neuroimmune signaling and HPA regulation [30]. The utility of GF models extends to fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) studies, where colonization with microbiota from diseased or stressed donors can transfer phenotypic traits including HPA dysregulation to recipient animals [28].

Microbiota Manipulation Approaches

Antibiotic-induced microbiota depletion provides a complementary approach to GF models, enabling investigation of microbiota contributions in adult organisms. Studies demonstrate that antibiotic treatment disrupts microbial community structure and diurnal rhythms of corticosterone release, leading to time-of-day-specific impairments in stress responsivity [35]. Probiotic interventions, typically utilizing specific bacterial strains such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, have been shown to normalize HPA activity and reduce depressive-like behaviors in both animal studies and human clinical trials [32]. For instance, L. reuteri has been identified as a candidate strain for regulating glucocorticoid rhythmicity [35]. Prebiotic administration, involving dietary compounds that selectively stimulate growth of beneficial bacteria, represents a complementary approach for modulating microbiota-HPA communication, primarily through enhancement of SCFA production [34].

Stress Exposure Paradigms

Controlled stress exposure represents an essential methodological component for investigating bidirectional microbiota-HPA interactions. Early life stress models, including maternal separation and limited nesting material, demonstrate that stress during critical developmental windows produces persistent HPA axis dysregulation associated with microbial dysbiosis, increased intestinal permeability, and immune activation [28]. In adult animals, chronic stress paradigms such as social defeat and chronic restraint stress produce robust alterations in gut microbiota composition, typically characterized by reduced abundance of beneficial bacteria (e.g., Lactobacillus) and increased proportion of potentially pathogenic taxa [32]. These stress-induced microbial changes are associated with exacerbated neuroinflammatory responses and altered HPA axis feedback sensitivity. Acute stress models further reveal rapid, stressor-induced changes in microbial community function and metabolite production, including increased catecholamine levels and altered tryptophan metabolism [34].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Investigating Microbiota-HPA Axis Interactions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Investigating microbiota-HPA axis interactions requires specialized research reagents and methodological approaches spanning microbiology, neuroendocrinology, and immunology. The following table summarizes essential research tools and their applications in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Microbiota-HPA Axis Research

| Research Tool | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gnotobiotic Models | Germ-free (GF) mice; Humanized microbiota mice [28] [30] | Establish causal relationships between specific microbes/microbial communities and HPA function [28] [30] | Requires specialized sterile isolators; colonization timing critical for developmental studies [28] |

| Probiotic Strains | Lactobacillus spp. (e.g., L. reuteri); Bifidobacterium spp. [32] [35] | Investigate therapeutic modulation of HPA axis; mechanism of action studies [32] [34] | Strain-specific effects; dosage and administration route critical; viability assessment essential [32] |

| Microbiome Sequencing | 16S rRNA gene sequencing; Shotgun metagenomics [36] [33] | Microbial community profiling; functional potential assessment; identification of microbial signatures [36] [33] | Choice of hypervariable region (16S); contamination controls; integration with metabolomic data [36] |

| HPA Axis Assessment | Corticosterone/Cortisol ELISA/RIA; CRF/ACTH immunoassays; Dexamethasone suppression test [28] [32] | Quantify HPA axis activity under basal and stress conditions; feedback sensitivity assessment [28] [32] | Diurnal rhythm considerations; appropriate stress paradigms; sampling time points critical [35] |

| Metabolomic Analysis | LC-MS/MS for SCFAs, neurotransmitters; Targeted metabolomics [34] [33] | Quantify microbial metabolites in gut, blood, brain; metabolic pathway analysis [34] [33] | Sample collection stability; comprehensive coverage; integration with microbial data [34] |

| Immune Profiling | Cytokine multiplex assays; Flow cytometry; TLR signaling assays [28] [30] | Characterize neuroimmune activation; inflammatory mediator quantification [28] [30] | Tissue-specific immune responses; activation states; cell population identification [30] |

Implications for Disease Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Development

Dysregulation of microbiota-HPA axis communication has been implicated in the pathophysiology of multiple neurological, psychiatric, and gastrointestinal disorders, revealing promising avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Stress-Related Psychiatric Disorders

Major depressive disorder is frequently associated with both HPA axis hyperactivity and gut microbial dysbiosis. Individuals with depression demonstrate distinct microbial signatures characterized by reduced abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria, altered tryptophan metabolism, and increased proinflammatory potential [33]. Preclinical studies demonstrate that fecal microbiota transplantation from depressed patients to germ-free rodents can induce depression-like behaviors, supporting a causal role for gut microbes in mood regulation [28]. Similarly, anxiety disorders have been linked to microbiota-HPA axis dysregulation, with probiotic interventions containing Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains demonstrating efficacy in reducing anxiety-like behaviors in both animal models and human populations [32] [33]. The adolescent period represents a particularly sensitive window for microbiota-HPA interactions, with stress during this developmental stage producing enduring effects on frontolimbic circuitry and stress responsiveness [32].

Neurodevelopmental and Neurodegenerative Disorders

Neurodevelopmental disorders including autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are associated with early-life alterations in gut microbiota composition and HPA axis function. Maternal immune activation models demonstrate that prenatal stress can induce microbial dysbiosis in offspring that persists into adulthood, accompanied by social behavior deficits and HPA axis dysregulation [31]. Neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease also demonstrate alterations in gut microbiota composition, with animal models suggesting that microbial manipulation can modify disease progression [36] [27]. The mechanisms linking gut microbiota to neurodegeneration likely involve bidirectional communication along the gut-brain axis, with microbial metabolites and immune activation contributing to neuroinflammation and protein aggregation [27].

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The growing understanding of microbiota-HPA axis interactions has stimulated development of novel therapeutic approaches targeting the gut microbiome for neuropsychiatric disorders. Probiotic interventions utilizing specific bacterial strains with neuroactive properties represent a promising strategy for HPA axis modulation, with clinical trials demonstrating beneficial effects on stress responsivity and mood [32] [33]. Prebiotic compounds that selectively enhance growth of beneficial taxa offer a complementary approach, primarily through stimulation of SCFA production [34]. Fecal microbiota transplantation represents a more intensive intervention that has shown efficacy in animal models for transferring behavioral phenotypes, highlighting the potential for microbiome-based therapeutics [28]. Future research directions include development of personalized microbiome-based interventions tailored to individual microbial and immune profiles, identification of microbiome-based biomarkers for stress susceptibility and treatment response, and exploration of dietary interventions designed to optimize microbiota-HPA axis communication [30] [33].

Advanced Assessment Techniques and Therapeutic Targeting of HPA Axis Pathways