Genetically Encoded Dopamine Sensors: A Comprehensive Guide for Neuroscience Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of genetically encoded fluorescent sensors for dopamine imaging, a revolutionary technology enabling high-resolution analysis of neurochemical dynamics.

Genetically Encoded Dopamine Sensors: A Comprehensive Guide for Neuroscience Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of genetically encoded fluorescent sensors for dopamine imaging, a revolutionary technology enabling high-resolution analysis of neurochemical dynamics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of sensor engineering, explores diverse methodological applications in vivo and in vitro, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and offers a comparative validation of the expanding sensor toolkit. By synthesizing the latest advances, this guide aims to empower the selection and implementation of these powerful tools to unravel dopamine's role in brain function, behavior, and neurological disorders.

The New Frontier in Neurochemical Imaging: Understanding Genetically Encoded Dopamine Sensors

Dopamine is a crucial monoamine neurotransmitter governing a wide array of brain functions, including motor control, reward, motivation, and learning [1]. Disruptions in dopaminergic signaling are implicated in numerous neurological and psychiatric disorders, such as Parkinson's disease, addiction, and schizophrenia [2]. For decades, our understanding of these processes has been driven by a suite of classical detection methods. However, the pursuit of finer mechanistic insights now reveals the significant constraints of these traditional tools. Microdialysis, fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV), and electrophysiology have been workhorses in neuroscience, yet each possesses inherent limitations that restrict our ability to observe the true spatiotemporal dynamics of dopamine signaling [3]. The emergence of genetically encoded sensors presents a transformative opportunity, necessitating a clear assessment of the methodological landscape this new technology aims to address.

Limitations of Traditional Dopamine Detection Methods

A critical evaluation of traditional methods reveals a consistent trade-off between temporal resolution, spatial precision, and chemical specificity.

Microdialysis

Microdialysis is considered a gold standard for its ability to measure a broad range of neurochemicals, including non-electroactive substances like neurotransmitters, amino acids, and neuropeptides [4]. Despite this broad scope, its limitations are profound.

- Poor Temporal and Spatial Resolution: The technique involves perfusing a probe with a semipermeable membrane and collecting dialysates over minutes, making it incapable of tracking sub-second dopamine transients that are fundamental to neural computation [3]. Furthermore, the probes are large (approximately 300 μm in diameter), causing significant tissue displacement and damage upon implantation [4]. This damage triggers a foreign body response, creating a gradient of disrupted dopamine activity around the probe track. Studies using FSCV have shown that evoked dopamine responses can be reduced by ~90% at a distance of 200 μm from a microdialysis probe and are completely lost when measured directly at the probe surface [4].

- Tissue Damage and Neurochemical Disruption: The implantation injury leads to instability in dopamine measurements for up to 24 hours post-implantation [4]. Histochemical studies clearly show traumatic injury near probe tracks, and the technique is seldom used for chronic, longitudinal studies due to these confounding effects [4].

Table 1: Key Limitations of Microdialysis

| Limitation | Impact on Dopamine Measurement |

|---|---|

| Low Temporal Resolution (minutes) | Cannot resolve rapid, phasic dopamine release events. |

| Large Probe Size (~300 μm) | Causes significant tissue damage and disrupts the local neurochemical environment. |

| Low Spatial Resolution | Provides poor anatomical specificity relative to neural circuits. |

| Limited Chemical Specificity | Requires subsequent analysis (e.g., HPLC) to identify and quantify dopamine in dialysate. |

Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV)

FSCV offers a dramatic improvement in temporal resolution, enabling detection of dopamine fluctuations on a sub-second timescale [5]. However, it faces other significant challenges.

- Limited Neurochemical Scope and Interferents: FSCV requires target molecules to be electroactive. This excludes a vast array of crucial neurochemicals [4]. Furthermore, its ability to distinguish dopamine from other molecules with similar redox potentials, such as norepinephrine, pH shifts, and changes in oxygenated blood flow, is limited and requires rigorous validation [5].

- Technical Complexity and Validation Challenges: The technique is often described as a "black art" to master [3]. Ensuring reliable measurements requires adherence to a set of "Five Golden Rules" for validation, which include identifying the electrochemical signature, anatomical confirmation, and pharmacological validation [5]. These validation steps are difficult or impossible to perform in a clinical setting, creating a major barrier to human translation [5].

- Tissue Interaction and Biofouling: While FSCV carbon-fiber microelectrodes are much smaller than microdialysis probes, they are still subject to issues like electrode biofouling, material deterioration, and signal loss during chronic recordings [5].

Table 2: Key Limitations of Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV)

| Limitation | Impact on Dopamine Measurement |

|---|---|

| Requires Electroactive Molecules | Cannot detect many key neurotransmitters (e.g., glutamate, GABA). |

| Susceptibility to Interferents | Distinguishing dopamine from pH changes, other catecholamines, and metabolites is challenging. |

| Technical "Black Art" | Requires significant expertise, limiting its broad adoption. |

| Stringent Validation Needed | Difficult to apply validation "Golden Rules" in clinical human studies. |

Electrophysiology

Electrophysiology, including patch-clamp recording, provides exquisite temporal resolution for measuring the electrical activity of neurons—the action potentials that ultimately drive neurotransmitter release [3].

- Indirect Measure of Neurotransmission: The primary limitation is that electrophysiology measures the electrical signal but cannot identify the specific neurotransmitters or neuromodulators released as a consequence of that activity [3]. While it can infer dopamine neuron activity based on firing patterns, it cannot directly measure dopamine concentration or dynamics in the extracellular space.

The following diagram summarizes the operational principles and core limitations of each traditional method within the experimental workflow.

The Emergence of Genetically Encoded Sensors

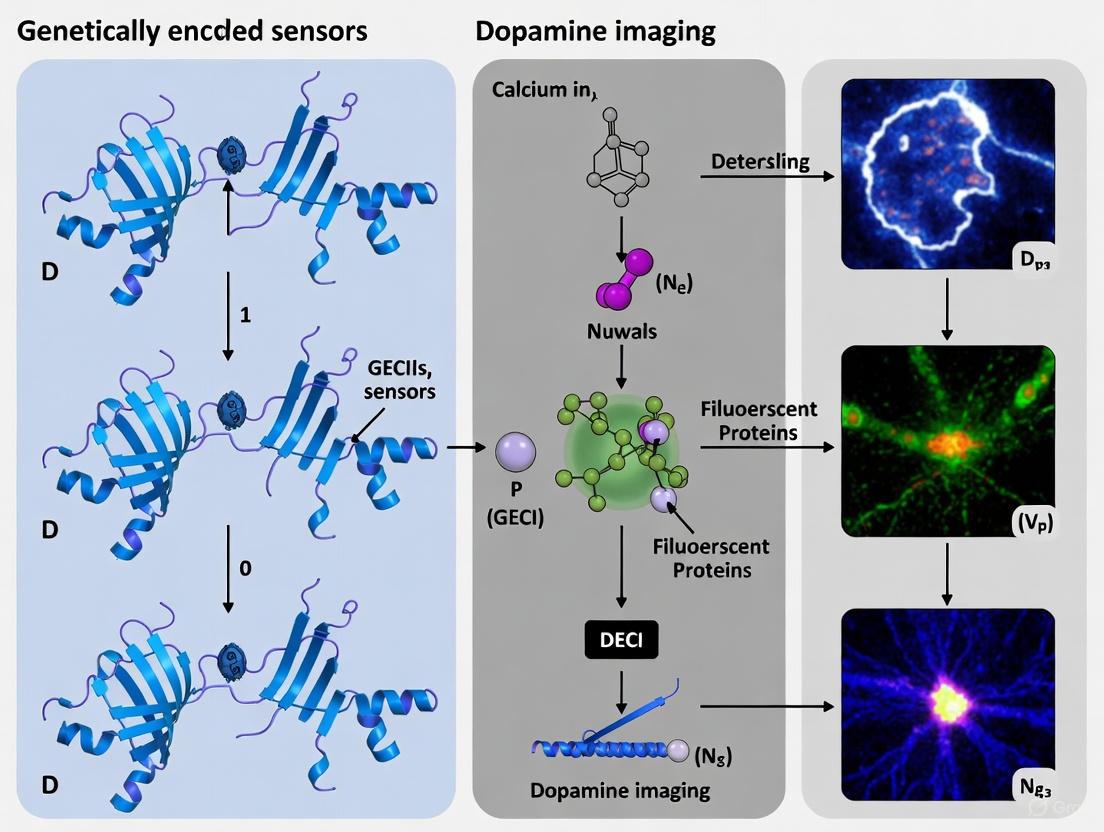

Driven by the limitations of traditional methods, the field has developed a new class of tools: genetically encoded fluorescent sensors for dopamine. These sensors, such as the dLight and GRAB-DA series, are engineered proteins that combine a dopamine receptor (the sensing domain) with a fluorescent protein (the reporter domain) [3] [1]. Upon binding dopamine, the sensor undergoes a conformational change that alters its fluorescence intensity, allowing direct, optical readout of dopamine dynamics with high specificity [1].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental design and signal transduction mechanism of these GPCR-based sensors.

Advantages Over Traditional Methods

Genetically encoded sensors directly address the critical gaps left by traditional methods:

- High Spatiotemporal Resolution: They enable detection of dopamine transients with sub-second kinetics and wave-like propagation across brain regions, a phenomenon previously difficult to observe [3] [1].

- Genetic and Cellular Specificity: Using viral vectors or transgenic animals, sensors can be targeted to specific cell types, brain regions, or even subcellular compartments, allowing researchers to probe dopamine signaling within defined neural circuits [1].

- Multiplexing Potential: The optical nature of these sensors allows for simultaneous recording of dopamine and other neurochemicals or calcium indicators in the same animal, providing a more integrated view of brain signaling [1].

- Ease of Use: Compared to the technical challenges of FSCV, sensor-based detection using fiber photometry or microscopy is more accessible to a wider range of neuroscience laboratories [3].

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Dopamine Detection Methods

| Method | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Chemical Specificity | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microdialysis | Minutes | Poor (~mm) | High (with HPLC) | Broad neurochemical scope | Severe tissue damage; low resolution |

| FSCV | Sub-second (ms-sec) | Good (~μm) | Moderate (with validation) | High temporal resolution for electroactive molecules | Limited molecule scope; technically complex |

| Electrophysiology | Millisecond | Single cell | None (indirect) | Direct measure of neuronal firing | Does not measure dopamine directly |

| Genetically Encoded Sensors | Sub-second | Single synapse to circuit | High | Cell-specific, high resolution in intact circuits | Requires genetic manipulation |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Protocol: Validating FSCV Measurements Using the "Five Golden Rules"

This protocol is essential for ensuring data accuracy and rigor in FSCV experiments, particularly in pre-clinical models [5].

Objective: To confirm that electrochemical signals recorded in vivo are specific for dopamine. Materials: FSCV setup with carbon-fiber microelectrode, reference electrode, stereotaxic equipment, stimulating electrode, and pharmacology agents.

Electrochemical Signature Identification:

- Implant the working electrode in the target brain region (e.g., striatum).

- Apply the standard triangular waveform (e.g., -0.4 V to +1.3 V and back, 10 Hz).

- Record background-subtracted cyclic voltammograms during electrical stimulation of dopamine pathways (e.g., medial forebrain bundle).

- Verify that the observed oxidation and reduction peaks align with the known signature for dopamine (e.g., oxidation at ~+0.6 V, reduction at ~-0.2 V).

Anatomical Validation:

- After the experiment, perfuse the animal and section the brain.

- Histologically verify the placement of the working and stimulating electrodes.

Kinetic Validation:

- Analyze the kinetics of the recorded signal. Electrically evoked dopamine release should show a rapid rise (milliseconds) followed by a slower decay (seconds) due to uptake via the dopamine transporter.

Pharmacological Validation:

- Administer a dopamine uptake inhibitor (e.g., nomifensine, 10 mg/kg i.p.). This should increase the amplitude and duration of the evoked dopamine signal.

- Administer a dopamine synthesis inhibitor (e.g., α-methyl-p-tyrosine) or a receptor agonist/antagonist to observe predictable changes in signal, further confirming chemical identity.

Protocol: Assessing Tissue Damage in Microdialysis

Objective: To evaluate the impact of microdialysis probe implantation on local dopamine circuitry. Materials: Microdialysis probe, FSCV setup, histology equipment.

- Probe Implantation: Implant a microdialysis probe into the striatum of an anesthetized rodent.

- FSCV Measurement at Varying Distances:

- Using a separate FSCV electrode, measure electrically evoked dopamine release at varying distances (e.g., 0 μm, 200 μm, 500 μm, 1000 μm) from the implanted microdialysis probe.

- Allow a stabilization period of several hours post-implantation before measurements.

- Data Analysis: Plot the amplitude of the evoked dopamine signal as a function of distance from the microdialysis probe. A significant gradient (e.g., 90% reduction at 200 μm) indicates substantial local tissue disruption [4].

- Histological Corroboration: Perfuse the animal and use immunohistochemistry (e.g., for tyrosine hydroxylase or glial fibrillary acidic protein) to visualize tissue damage and glial activation along the probe track.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and tools essential for research in dopamine detection.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Dopamine Detection Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| dLight Sensors | Genetically encoded fluorescent sensor for monitoring dopamine dynamics with high temporal resolution. | dLight1, dLight1.1, dLight1.2 [3] |

| GRAB-DA Sensors | Genetically encoded fluorescent sensor based on the human dopamine D2 receptor. | GRABDA1m, GRABDA2m, GRAB_DA4m [1] |

| 123I-FP-CIT (DaTscan) | SPECT radioligand for imaging the dopamine transporter (DAT) in the clinical diagnosis of parkinsonism. | DaTSCAN [6] |

| Carbon-Fiber Microelectrode | Working electrode for FSCV; provides high spatial and temporal resolution for electroactive neurotransmitters. | 7 μm diameter carbon fiber [4] |

| Microdialysis Probe | For sampling extracellular fluid across a semipermeable membrane to measure a wide range of neurochemicals. | ~300 μm diameter probe [4] |

| Nomifensine | Dopamine uptake inhibitor; used for pharmacological validation of dopamine signals in FSCV. | Nomifensine maleate [4] |

| AAV-hSyn-DIO-dLight | Adeno-associated virus vector for cell-type-specific expression of dLight sensor in Cre-recombinase expressing neurons. | AAV serotype (e.g., AAV1, AAV5) [1] |

Traditional methods for dopamine detection—microdialysis, FSCV, and electrophysiology—have provided foundational knowledge but are constrained by significant limitations in resolution, specificity, and minimal invasiveness. The critical need to observe dopamine dynamics within the intact complexity of neural circuits has driven the development and adoption of genetically encoded sensors. These new tools illuminate the brain's chemical dialogue with unprecedented clarity, enabling discoveries such as the wave-like propagation of dopamine and its fast, coordinated fluctuations with other neuromodulators like acetylcholine [3]. As these sensors continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly accelerate the pace of discovery in basic neuroscience and the development of novel therapeutics for brain disorders.

Genetically encoded sensors for dopamine, primarily from the dLight and GRABDA families, are engineered proteins that transform the transient, invisible event of dopamine binding into a stable, measurable fluorescent signal [3] [7]. These tools have revolutionized neuroscience by enabling the real-time visualization of dopamine dynamics in living brains with high spatiotemporal resolution, molecular specificity, and cell-type-specific targeting [8] [3]. Their development addresses the limitations of classical techniques like fast-scan cyclic voltammetry and microdialysis, which often struggle with molecular specificity or temporal resolution [8] [3].

The core scaffold for these sensors is a native dopamine G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), which has evolved for high specificity and affinity for dopamine [7]. The fundamental engineering principle involves coupling the conformational change in the receptor upon dopamine binding to a change in the brightness of a fluorescent protein, allowing dopamine concentration to be reported optically [9] [7].

The Molecular Mechanism of Signal Conversion

The process by which dopamine binding is converted into a fluorescent readout can be broken down into a sequence of key molecular events, illustrated in the following diagram.

Key Stages in the Signaling Mechanism

- Dopamine Binding: The sensor is in a basal, low-fluorescent state. The extracellular domain of the GPCR scaffold serves as the recognition module, waiting for its specific ligand [7].

- Conformational Change in the GPCR: Dopamine binding stabilizes an active receptor conformation. The most critical structural rearrangement is the outward movement and rotation of transmembrane helix 6 (TM6), accompanied by shifts in TM5 and TM7 [9]. This movement is central to the sensor's function.

- Mechanical Transduction to the Fluorescent Protein: A circularly permuted green fluorescent protein (cpGFP) is strategically inserted into the third intracellular loop (ICL3) of the GPCR, which connects TM5 and TM6 [9] [7]. The conformational change, particularly the movement of TM5 and TM6, mechanically pulls on the cpGFP.

- Fluorescence Enhancement: This mechanical pull alters the chromophore environment within the cpGFP, reducing the quenching effect of nearby amino acids and leading to a significant increase in fluorescence intensity [8] [7]. The magnitude of this increase is proportional to the concentration of dopamine, providing a quantitative optical readout.

Quantitative Properties of Key Dopamine Sensors

The palette of available sensors allows researchers to select a tool matched to their experimental needs, based on quantitative properties like affinity, dynamic range, and selectivity.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of Selected dLight and GRABDA Sensors

| Sensor Name | GPCR Scaffold | Affinity (EC₅₀) | Dynamic Range (ΔF/F₀) | Dopamine vs. Norepinephrine Selectivity | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dLight1.1 | D1R | 40 nM | 2.3 | 12-fold | High-affinity detection in sparsely innervated regions [10] |

| dLight1.3b | D1R | Not Specified | 6.6 | 16-fold | Conditions requiring maximum brightness change [10] |

| GRABDA1M | D2R | 4 nM - 1.8 µM | 1.9 | 21-fold | High-affinity detection of low DA concentrations [10] |

| GRABDA1H | D2R | 1 nM | 2.5 | 8-fold | Ultra-high-affinity detection of subtle fluctuations [10] |

| GRABDA2M | D2R | 4 nM - 1.8 µM | 4.8 | 14-fold | Balanced high dynamic range and high affinity [10] |

Table 2: Sensor Selection Guide Based on Experimental Goals

| Experimental Goal | Recommended Sensor Properties | Example Sensors |

|---|---|---|

| High Affinity for Sparse DA | Low nM affinity | GRABDA1H, GRABDA1M [8] [10] |

| Fast Kinetics for Rapid Release | Fast on/off rates (kon, koff) | dLight1.3 variants [8] |

| Maximum Signal Change | Large dynamic range (ΔF/F₀) | dLight1.3b, GRABDA2M [10] |

| Multiplexing with Other Sensors | Red-shifted emission spectrum | RdLight1 [8] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Applications

Protocol: Using DA "Sniffer Cells" for In Vitro Dopamine Detection

This protocol utilizes stable cell lines (e.g., Flp-In T-REx 293 cells) with inducible expression of dLight or GRABDA sensors for quantitative, high-throughput dopamine measurements without viral delivery [10].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Cell Culture and Sensor Induction:

- Culture Flp-In T-REx 293 sniffer cell lines expressing the sensor of choice (e.g., dLight1.3b for large signals or GRABDA1H for high sensitivity) [10].

- Induce sensor expression by adding tetracycline (e.g., 1 µg/mL) to the culture medium 24 hours before the experiment.

- Experimental Setup:

- Plate induced cells into a clear-bottom, black-walled 96-well plate at a density of ~50,000 cells per well.

- Allow cells to adhere overnight in a culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂).

- Sample Application and Fluorescence Recording:

- Replace the culture medium with a physiological buffer (e.g., HEPES-buffered saline).

- Establish a baseline fluorescence (F₀) using a plate reader (e.g., excitation 488 nm, emission 510-540 nm).

- Apply the sample containing dopamine (e.g., supernatant from stimulated neuronal cultures, brain tissue homogenate, or drug solution).

- Monitor the fluorescence intensity (F) in real-time for 1-10 minutes.

- Validation and Data Analysis:

- Pharmacological Validation: In separate wells, pre-incubate cells with a dopamine receptor antagonist (e.g., 10 µM SCH-23390 for dLight1 or 10 µM raclopride for GRABDA) for 15 minutes before sample application to confirm the response is sensor-specific [10].

- Quantification: Calculate the fluorescence change as ΔF/F = (F - F₀)/F₀.

- Concentration-Response: Generate a standard curve by applying known concentrations of dopamine (e.g., 1 nM to 10 µM) to the sniffer cells. Fit the data with a sigmoidal curve to quantify dopamine in unknown samples.

Protocol: In Vivo Dopamine Imaging via Fiber Photometry

This protocol describes the use of fiber photometry in freely moving mice to record dopamine dynamics in specific brain regions with subsecond resolution [8] [3].

Key Steps:

- Sensor Delivery:

- Inject an adeno-associated virus (AAV) encoding the sensor (e.g., AAV-hSyn-dLight1.1 or AAV-hSyn-GRABDA1h) into the target brain region (e.g., nucleus accumbens or dorsal striatum) of an anesthetized mouse. Use a cell-type-specific promoter (e.g., hSyn for pan-neuronal expression) for targeted sensor expression.

- Optical Implant:

- Implant an optical fiber (e.g., 400 µm core diameter) above the viral injection site to allow for light delivery and fluorescence collection.

- Data Acquisition:

- After a 2-4 week recovery and sensor expression period, tether the mouse to a fiber photometry system.

- Deliver excitation light (e.g., ~465-488 nm for green sensors) through the optical fiber and record the emitted fluorescence signal (~500-540 nm) from the sensor.

- Simultaneously record the animal's behavior (e.g., on video) to correlate dopamine transients with specific actions or stimuli.

- Data Processing:

- Process the raw fluorescence signal to remove motion artifacts and bleaching effects. This often involves isosbestic control signals or digital filtering.

- Align the fluorescence traces with behavioral timestamps to identify stimulus-locked or action-locked dopamine release events.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for GPCR-Based Dopamine Sensor Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Utility | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| dLight & GRABDA Sensor Families | Core detection tools with varying affinity and kinetics for different experimental contexts [8] [10] | In vivo photometry (dLight1.3), in vitro sniffer assays (GRABDA1H) |

| AAV Vectors for Sensor Expression | Enables targeted, efficient, and long-term sensor expression in specific brain regions and cell types in vivo [3] | Neuronal circuit-specific dopamine recording (e.g., AAV-hSyn-dLight) |

| "Sniffer" Cell Lines | Stable, inducible cell lines for radioactivity-free, high-throughput in vitro and ex vivo dopamine measurements [10] | Measuring DA release from cultured neurons, tissue content, drug screening |

| DA Receptor Antagonists | Pharmacological controls to validate the specificity of the sensor signal [10] | SCH-23390 (D1R-antagonist) for dLight; Raclopride (D2R-antagonist) for GRABDA |

| Fiber Photometry Systems | Integrated hardware for real-time fluorescence recording in freely behaving animals [8] [3] | Correlating dopamine dynamics with behavioral tasks like reward learning |

Genetically encoded fluorescent sensors for dopamine represent a transformative technological advancement in neuroscience, enabling real-time detection of neuromodulator dynamics with high spatiotemporal resolution in living systems. These tools have emerged as superior alternatives to traditional methods like microdialysis and fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV), which face limitations in temporal resolution, spatial precision, and molecular specificity [8] [11]. The core design principle of these sensors involves integrating a dopamine-sensitive G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) domain with a circularly permuted fluorescent protein (cpFP). Dopamine binding induces a conformational change in the receptor, which alters the chromophore environment of the cpFP and results in a measurable change in fluorescence intensity [8] [1] [12]. This molecular design allows researchers to optically monitor dopamine fluctuations as they occur in vivo during behavioral experiments, providing unprecedented insight into the roles of dopamine in reward, motivation, learning, and motor control [13] [1].

The two primary families of dopamine sensors—dLight and GRABDA—along with the spectrally distinct RdLight platform, have distinct properties and applications. When implementing these tools, researchers must consider that there is no universal 'one-size-fits-all' sensor [8]. Sensor properties—most critically their affinity, dynamic range, kinetics, and spectral characteristics—must be carefully matched to the experimental context, including the brain region of interest (with its specific local dopamine levels), the temporal dynamics of the behavior under study, and the requirements for multiplexing with other optical tools [8] [10]. This application note provides a comprehensive guide to the dLight, GRABDA, and RdLight platforms, offering detailed comparisons, experimental protocols, and implementation frameworks to inform their effective application in basic neuroscience and drug discovery research.

The dLight Sensor Platform

Design Principles and Development

The dLight sensor platform was engineered through a systematic approach of replacing the third intracellular loop of human dopamine receptors (D1, D2, or D4) with a circularly permuted green fluorescent protein (cpGFP) module derived from GCaMP6 [12]. This strategic design creates a chimeric protein that binds dopamine with high affinity and undergoes a conformational change that directly translates into an increase in cpGFP fluorescence. A critical feature of the dLight design is its decoupling from downstream signaling cascades, meaning sensor expression does not appear to interfere with native GPCR signaling pathways, thereby providing a pure reporting function without perturbing the underlying biology [12]. The dLight1 series encompasses multiple variants (e.g., dLight1.1, dLight1.2, dLight1.3a, dLight1.3b) with engineered differences in their dynamic ranges and affinities for dopamine, offering researchers a toolkit to match sensor properties to specific experimental needs [10] [12].

Key Sensor Variants and Properties

Table 1: Characteristics of Key dLight Sensor Variants

| Sensor Variant | Dynamic Range (ΔF/F0) | Detection Range | DA Affinity (EC50) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dLight1.1 | ~230% [12] | ~40 nM - 17 µM [10] | Lower affinity | General purpose in vivo imaging |

| dLight1.2 | ~316% [10] | ~40 nM - 17 µM [10] | Medium affinity | Behaviorally-relevant transients |

| dLight1.3a | ~498% [10] | ~40 nM - 17 µM [10] | Medium affinity | High signal-to-noise applications |

| dLight1.3b | ~661% [10] | ~40 nM - 17 µM [10] | Medium affinity | Maximum brightness applications |

The dLight platform exhibits high molecular specificity for dopamine over other neurotransmitters, though some cross-reactivity with noradrenaline has been observed. Quantitative assessment reveals approximately 12-18 fold selectivity for dopamine over noradrenaline across different dLight variants [10]. The sensors demonstrate fast kinetics compatible with tracking the rapid dynamics of dopamine release and clearance, with performance characteristics suitable for detecting phasic dopamine signals that occur on subsecond timescales during behavioral tasks [8] [12]. This combination of properties has established dLight as a powerful tool for investigating dopamine dynamics in contexts ranging from reward processing to aversive learning [13].

Figure 1: dLight Sensor Design Principle. Dopamine binding to the receptor domain induces a conformational change that alters the cpGFP environment, resulting in increased fluorescence.

The GRABDA Sensor Platform

Structural Basis and Engineering

The GRABDA (GPCR Activation-Based Dopamine) sensor platform shares a similar conceptual framework with dLight but incorporates distinct engineering approaches. GRABDA sensors are also constructed by inserting a cpGFP into a dopamine receptor scaffold, but utilize different insertion points and receptor conformations to achieve their signaling properties [14] [1]. The GRAB family includes sensors derived from both D1-like and D2-like dopamine receptors, with the latter generally exhibiting higher affinity for dopamine,

reflecting the innate pharmacological properties of their parent receptors [10]. This fundamental design difference results in GRABDA sensors being particularly sensitive to lower concentrations of dopamine, making them exceptionally suited for monitoring dopamine dynamics in brain regions with sparse dopaminergic innervation [8] [14]. The GRABDA platform continues to evolve with the recent development of next-generation sensors with improved signal-to-noise ratios and additional spectral variants [1].

Key Sensor Variants and Properties

Table 2: Characteristics of Key GRABDA Sensor Variants

| Sensor Variant | Dynamic Range (ΔF/F0) | Detection Range | DA Affinity (EC50) | Selectivity (DA:NE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRABDA1M | ~186% [10] | ~4 nM - 1.8 µM [10] | High affinity | 21:1 [10] |

| GRABDA1H | ~249% [10] | ~1 nM - 1.8 µM [10] | Very high affinity | 8:1 [10] |

| GRABDA2M | ~477% [10] | ~4 nM - 1.8 µM [10] | High affinity | 14:1 [10] |

GRABDA sensors exhibit exceptional sensitivity to low dopamine concentrations, with the GRABDA1H variant capable of detecting dopamine at concentrations as low as 1 nM [10]. This remarkable sensitivity makes these sensors ideally suited for investigating dopamine signaling in sparsely innervated brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala, where dopamine concentrations are significantly lower than in the densely innervated striatum [8]. The GRABDA platform has been successfully implemented across diverse model organisms including flies, fish, and mice [14], demonstrating its broad utility in comparative neuroscience and its robustness across different experimental preparations.

The RdLight Sensor Platform

Spectral Advantages and Multiplexing Capabilities

The RdLight platform represents a spectral extension of the dLight design principle, incorporating red-shifted fluorescent proteins rather than green cpGFP. This critical engineering achievement enables multiplexed imaging with green indicators such as GCaMP (for calcium imaging) or other green-emitting neurotransmitter sensors [8] [15]. The red-shifted spectral properties of RdLight sensors provide several distinct experimental advantages beyond multiplexing, including reduced tissue autofluorescence, decreased light scattering, and potentially deeper tissue penetration when using two-photon microscopy techniques [8] [15]. While comprehensive quantitative characterization of RdLight sensors is less extensively documented in the searched literature compared to their green counterparts, their development addresses a critical need in modern neuroscience for tools that enable simultaneous monitoring of multiple neural signals within the same circuit or even the same cell [8].

The availability of red-shifted dopamine sensors like RdLight, along with other recently developed red and yellow variants (YdLight), creates exciting opportunities for investigating interactions between dopamine and other signaling molecules. For example, researchers can now simultaneously monitor dopamine release (using RdLight) and neuronal activity (using GCaMP) in the same population of cells, or track the coordinated release of dopamine and other neuromodulators such as acetylcholine or norepinephrine [8] [12]. This multi-modal imaging approach is transforming our understanding of how neuromodulators interact to shape neural circuit function and behavior.

Comparative Analysis of Sensor Properties

Performance Characteristics Across Platforms

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Dopamine Sensor Families

| Sensor Property | dLight Platform | GRABDA Platform | RdLight Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Receptor | D1-like [12] | D1-like & D2-like [14] [1] | D1-like [8] |

| Dynamic Range | High (up to 661% ΔF/F0) [10] | Moderate to High (186-477% ΔF/F0) [10] | Similar to dLight (quantitative data limited) [8] |

| Affinity Range | Lower affinity variants (nM-µM range) [10] | Higher affinity variants (low nM range) [10] [14] | Variants with different affinities available [8] |

| Detection Range | ~40 nM - 17 µM [10] | ~1 nM - 1.8 µM [10] | Not fully characterized in searched literature |

| Selectivity (DA:NE) | 12-18:1 [10] | 8-21:1 [10] | Preserved from dLight design [8] |

| Kinetics | Fast (subsecond resolution) [8] [12] | Fast (subsecond resolution) [14] [1] | Fast (subsecond resolution) [8] |

| Spectral Class | Green [12] | Green [14] | Red [8] |

| Key Applications | Striatal regions with high DA, behavior studies [8] [13] | Sparsely innervated regions, low DA concentrations [8] [14] | Multiplexing with green indicators [8] |

Guidelines for Sensor Selection

Choosing the appropriate dopamine sensor requires careful consideration of multiple experimental parameters. The following guidelines summarize key selection criteria based on sensor properties and experimental needs:

Match sensor affinity to expected dopamine concentrations: For densely innervated regions like dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens, dLight sensors are often optimal. For sparsely innervated regions like prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus, and hippocampus, the higher-affinity GRABDA sensors (particularly GRABDA1H and GRABDA1M) are preferable [8] [10].

Prioritize dynamic range for signal detection: When detecting small phasic changes in dopamine against a stable baseline, sensors with higher dynamic range (dLight1.3b, GRABDA2M) provide superior signal-to-noise ratio [10].

Consider temporal requirements: For experiments requiring resolution of rapidly changing dopamine signals (e.g., during reward prediction error tasks), sensors with faster kinetics are essential [8] [1].

Plan for multiplexing experiments: When simultaneously imaging dopamine with other green fluorescent indicators (e.g., GCaMP for calcium), RdLight sensors enable spectral separation [8] [12].

Account for molecular specificity needs: In brain regions with overlapping dopamine and norepinephrine signaling, consider sensors with higher selectivity ratios (e.g., GRABDA1M with 21:1 selectivity) [10].

Figure 2: Dopamine Sensor Selection Guide. A decision tree for selecting the optimal dopamine sensor based on experimental parameters including brain region, multiplexing needs, and kinetic requirements.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

In Vivo Imaging Using Fiber Photometry

Purpose: To measure dopamine dynamics in specific brain regions of freely behaving animals. Workflow:

- Sensor Expression: Deliver sensor to target brain region using stereotaxic injection of adeno-associated virus (AAV) encoding the dopamine sensor (e.g., AAV-hSyn-dLight1.1 or AAV-hSyn-GRABDA1M). Allow 3-6 weeks for adequate expression [8] [1].

- Optic Cannula Implantation: Implant a fiber optic cannula above the target region and secure to the skull with dental cement [1].

- Signal Acquisition: Connect the implanted fiber to a fiber photometry system. Excite the sensor at appropriate wavelengths (e.g., ~470 nm for green sensors). Collect emitted fluorescence through the same fiber [1].

- Data Processing: Calculate ΔF/F as (F - F₀)/F₀, where F₀ is the baseline fluorescence. Apply appropriate filtering and analyze dopamine transients time-locked to behavioral events [8] [1].

Key Considerations:

- Include motion and bleaching correction in analysis pipeline.

- Use isosbestic control signals when possible to account for motion artifacts.

- For GRABDA sensors, consider the higher sensitivity and potential saturation in high dopamine regions [10].

In Vitro Detection Using Sniffer Cells

Purpose: To create a versatile, virus-free platform for dopamine detection in cell culture systems and tissue preparations. Workflow:

- Cell Line Generation: Stably transfer Flp-In T-REx 293 cells with inducible dLight or GRABDA constructs using the Flp-In system to ensure homogeneous expression [10].

- Sensor Induction: Treat sniffer cells with tetracycline (1 μg/mL, 24 hours) to induce sensor expression before experiments [10].

- Sample Application: Plate induced sniffer cells and apply biological samples (e.g., neuronal culture medium, brain slice supernatant, or tissue homogenate) [10].

- Fluorescence Detection: Measure fluorescence changes using plate readers or fluorescence microscopy. For microscopy, use appropriate filter sets (e.g., 470/40 nm excitation, 525/50 nm emission for green sensors) [10].

- Quantification: Generate standard curves with known dopamine concentrations for quantification [10].

Key Applications:

- Recording endogenous dopamine release from cultured neurons.

- Measuring dopamine content in striatal tissue samples.

- High-throughput screening of dopamine transporter (DAT) ligands and uptake inhibitors [10].

Multiplexed Imaging with Calcium Indicators

Purpose: To simultaneously monitor dopamine signaling and neuronal activity in the same population of cells. Workflow:

- Dual Sensor Expression: Co-express a red-shifted dopamine sensor (RdLight) with a green calcium indicator (GCaMP) in the target brain region using appropriate viral vectors [8] [12].

- Microscopy Setup: Use a two-photon microscope with dual-channel detection capabilities. Optimize laser wavelengths for simultaneous excitation of both sensors (e.g., 920-940 nm for GCaMP and RdLight) [8].

- Spectral Separation: Implement appropriate emission filters to cleanly separate green (500-550 nm) and red (580-630 nm) emission signals [8] [12].

- Data Analysis: Register and analyze signals from both channels, calculating ΔF/F for each sensor independently. Correlate dopamine transients with calcium dynamics to infer relationships between neuromodulator release and neuronal activity [12].

Representative Findings: This approach has revealed how footshock stress decreases dopamine signaling in nucleus accumbens (detected by dLight) while increasing overall neuronal activity (detected by jRGECO1a), demonstrating complex relationships between neuromodulator availability and circuit output [12].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Dopamine Sensor Implementation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| AAV-hSyn-dLight1.X | In vivo sensor expression under neuronal promoter | Use for specific expression in neurons; optimize titer for brain region [8] [12] |

| AAV-hSyn-GRABDAX | In vivo expression of GRABDA sensors | Higher affinity variants ideal for sparsely innervated regions [8] [14] |

| Fiber Optic Cannulas | Light delivery/collection for photometry | Match fiber diameter to target region size; consider numerical aperture [1] |

| BacMam 2.0 Technology | Gene delivery for primary neurons | Enables transduction of difficult-to-transfect cells including neurons [16] |

| CellLight Reagents | Organelle-specific labeling in live cells | Use for morphological reference in imaging experiments [16] |

| Rhod-3 AM | Red-shifted calcium indicator | Compatible with multiplexing using green dopamine sensors [16] |

| Tetrodotoxin (TTX) | Voltage-gated sodium channel blocker | Use to confirm action potential-dependent dopamine release [10] |

| Dopamine Receptor Antagonists | Pharmacological validation of sensor response | Confirm specificity of fluorescent responses (e.g., SCH23390 for D1-based sensors) [10] |

| DAT Inhibitors (Nomifensine) | Dopamine transporter blockade | Use to probe reuptake mechanisms and increase extracellular dopamine [10] |

Applications in Psychiatric Research and Drug Discovery

Genetically encoded dopamine sensors are revolutionizing psychiatric research by enabling precise functional characterization of neurochemical dysregulation in disease models and providing mechanistic insights into therapeutic interventions. These tools have been particularly impactful in several key areas:

Depression and Stress Models: dLight has revealed how increased anhedonia in female animals correlates with decreased dopamine release in the dorsomedial striatum, highlighting sex-specific mechanisms in depression [13]. GRABNE (a norepinephrine sensor) has enabled observations that low corticosterone rats display increased hippocampal norepinephrine levels correlated with decreased REM sleep, informing our understanding of biological risk factors for stress susceptibility [13].

Substance Use Disorders: dLight has been instrumental in demonstrating how heroin use changes dopamine-driven reward circuits, enhancing reward responses upon entry to drug-associated environments [13]. The dynorphin-binding sensor kLight has elucidated how morphine withdrawal induces endogenous dynorphin release in prefrontal cortex, a mechanism known to cause aversion and disrupt cognition [13].

Drug Safety Assessment: dLight has been employed to compare the effects of ketamine and cocaine on addiction-related functional changes, providing evidence that ketamine does not induce the full array of neuroadaptive changes associated with cocaine, informing safety assessments of ketamine as an antidepressant [13].

Parkinson's Disease Research: Dopamine sensors have enabled high-sensitivity detection of dopamine deficits along disease progression. Using dLight, researchers have demonstrated that disruption of mitochondrial complex I corresponds with progressive loss of dopaminergic signaling first in dorsal striatum, with eventual depletion in substantia nigra, modeling the staging of dopamine depletion in Parkinson's disease [13].

These applications demonstrate how genetically encoded dopamine sensors are transforming our understanding of psychiatric disease mechanisms and creating new opportunities for therapeutic development through their ability to provide direct, real-time readouts of neurochemical dynamics in disease models and during drug interventions.

The study of dopamine neurotransmission has been revolutionized by the development of genetically encoded sensors, enabling the real-time detection of this crucial neuromodulator with high spatiotemporal precision in behaving animals. These tools have addressed significant limitations of traditional methods such as microdialysis and fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, which offered insufficient temporal resolution or low molecular specificity [17] [1]. The core architecture of these modern sensors strategically integrates circularly permuted green fluorescent protein (cpGFP) with dopamine receptor scaffolds through precision-optimized linkers [18]. This document details the principles, optimization protocols, and practical applications of these biosensor components, providing a framework for their use in advanced neuroscience research and drug development.

Core Engineering Principles

The Central Component: Circularly Permuted GFP (cpGFP)

The functionality of genetically encoded biosensors hinges on the unique properties of circularly permuted GFP (cpGFP). In a standard GFP, the N- and C-termini are located distantly from the central chromophore. Circular permutation involves fusing the original termini with a peptide linker and creating new termini at a site near the chromophore [19]. This strategic relocation imparts greater conformational flexibility to the FP, making the chromophore's fluorescence highly sensitive to environmental changes.

Molecular Mechanism: The new termini are typically formed within a surface-oriented loop, placing the chromophore in a more labile structural context. When integrated into a sensor, the cpGFP is flanked by linkers and embedded within a sensory domain. Conformational changes in the sensory domain upon ligand binding are directly transferred to the cpGFP, altering the chromophore's protonation state or local environment, which in turn modulates fluorescence intensity [19] [15]. This design is the foundation for single-FP-based intensity sensors, simplifying optical setup compared to FRET-based systems.

Historical Development: The tolerance of GFP for circular permutation was first reported in 1999 [19]. This discovery paved the way for seminal sensors like camgaroo1 and GCaMP, which inserted cpGFP into calmodulin. The success of these early sensors established cpGFP as the reporter module of choice for a generation of biosensors targeting ions, neurotransmitters, and neuromodulators [20].

The Sensing Module: Dopamine Receptor Scaffolds

The molecular specificity of dopamine sensors is conferred by their sensing module, derived from native dopamine receptors. These G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) undergo specific conformational rearrangements upon dopamine binding.

Scaffold Selection: The human dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) is a preferred scaffold due to its high affinity for dopamine and excellent membrane trafficking properties [18]. The development of GRABDA sensors involved inserting cpGFP into the third intracellular loop (ICL3) of the D2R, a region known to undergo significant movement during receptor activation [18].

Mechanism of Activation: Upon dopamine binding, the receptor transitions to an active state, characterized by an outward movement of transmembrane helix 6 (TM6) [21]. This structural shift is mechanically transmitted to the integrated cpGFP, resulting in a measurable increase in fluorescence. A key engineering success has been mutating these chimeric sensors to decouple them from native G-protein and β-arrestin signaling pathways, allowing them to report dopamine binding without interfering with normal cellular physiology or causing sensor internalization [18].

The Critical Bridge: Linker Optimization

The peptide linkers connecting the cpGFP to the dopamine receptor scaffold are not mere passive connectors; they are critical determinants of sensor performance. Optimal linkers efficiently transduce the conformational change from the receptor to the cpGFP.

Performance Impact: The length, flexibility, and amino acid composition of these linkers are paramount. For instance, during the development of the STEP biosensor, systematic linker optimization increased the dynamic range (ΔF/F0) from 1.0 to 3.4 [20]. Suboptimal linkers can dampen or completely prevent the fluorescence change, rendering the sensor non-functional.

Optimization Strategies: Linker optimization is typically achieved through randomized mutagenesis of linker sequences followed by high-throughput screening. The goal is to identify linkers that provide the appropriate mechanical coupling without restricting the necessary conformational flexibility of either the receptor or the cpGFP [20].

Performance Characterization & Quantitative Data

Rigorous characterization of sensor performance is essential for selecting the appropriate tool for a given experimental context. Key parameters include dynamic range, affinity, kinetics, and specificity.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Representative Dopamine Sensors

| Sensor Name | Dynamic Range (ΔF/F0) | Affinity (EC50 / Kd) | On Kinetics (ton) | Off Kinetics (toff) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRABDA1m | ~90% [18] | ~130 nM [18] | 60 ± 10 ms [18] | 0.7 ± 0.06 s [18] | Medium affinity, fast off-kinetics |

| GRABDA1h | ~90% [18] | ~10 nM [18] | 140 ± 20 ms [18] | 2.5 ± 0.3 s [18] | High affinity for low-concentration detection |

| dLight1 | ~90% [1] | ~10 nM - ~4 μM variants [1] | Sub-second [1] | Sub-second to seconds [1] | Expanded palette for multiplexing [1] |

| G-Flamp1 (cAMP) | 1100% [22] | 2.17 μM (for cAMP) [22] | 0.20 s [22] | 0.087 s [22] | Highlights performance potential of cpGFP design |

Beyond the core performance metrics, several other factors are critical for in vivo application:

- Molecular Specificity: GRABDA sensors show high specificity for dopamine over other neurotransmitters like glutamate, GABA, and acetylcholine. A modest cross-reactivity with norepinephrine exists but is minimal at physiological concentrations due to a ~10-fold lower EC50 for DA than for NE [18].

- Brightness & Photostability: These sensors exhibit approximately 70% of the brightness of EGFP and photostability comparable to or better than other cpEGFP-based sensors, enabling sustained imaging sessions [18].

- Spectral Properties: Most first-generation sensors are green fluorescent. However, red-shifted variants are being actively developed to enable multiplexed imaging with other optogenetic actuators or sensors [20] [1].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Sensor Characterization in Cell Culture

This protocol outlines the steps for validating the basic function and pharmacological properties of a dopamine sensor in heterologous cells and neurons.

Applications: Initial validation, dose-response characterization, and specificity testing.

Materials:

- Plasmids: Sensor plasmid (e.g., GRABDA1m, GRABDA1h).

- Cell Lines: HEK293T cells.

- Culture Reagents: Standard cell culture media and transfection reagents.

- Imaging Setup: Epifluorescence or conf microscope, perfusion system.

- Pharmacological Agents: Dopamine hydrochloride, receptor antagonists (e.g., Haloperidol, Eticlopride), other neurotransmitters for specificity tests.

Procedure:

- Cell Culture & Transfection: Culture HEK293T cells in standard conditions. Transiently transfect cells with the sensor plasmid using a standard method (e.g., PEI, calcium phosphate).

- Image Acquisition: 24-48 hours post-transfection, mount coverslips on the microscope stage. Use a 488 nm laser for excitation and collect emission at 510-540 nm. Maintain temperature at 35-37°C.

- Dose-Response Measurement:

- Continuously perfuse cells with buffer.

- Apply increasing concentrations of dopamine (e.g., 1 nM to 100 μM) for 10-30 seconds each, with a 3-5 minute washout period between applications.

- Record fluorescence changes (F).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate ΔF/F0 = (F - F0) / F0, where F0 is the baseline fluorescence.

- Plot ΔF/F0 against dopamine concentration and fit with a sigmoidal (e.g., Hill) equation to determine EC50 and maximum ΔF/F0.

- Specificity & Pharmacology:

- Repeat the above, applying a saturating dose of dopamine in the presence or absence of antagonists (e.g., 10 μM Haloperidol) to confirm the response is receptor-mediated.

- Apply other neurotransmitters (e.g., NE, serotonin, glutamate) at physiologically relevant concentrations to test for cross-reactivity.

Protocol: In Vivo Dopamine Imaging with Fiber Photometry

This protocol describes the use of fiber photometry to record bulk dopamine signals in specific brain regions of freely behaving mice.

Applications: Monitoring dopamine dynamics during behavior, learning, and in disease models.

Materials:

- Viral Vector: AAV encoding sensor (e.g., AAV-hSyn-GRABDA1m).

- Animals: Mice (e.g., C57BL/6J).

- Surgical Equipment: Stereotaxic apparatus, microsyringe.

- Implants: Optical ferrule and fiber cannula.

- Recording System: Fiber photometry system (LEDs, dichroic mirrors, detectors), behavior arena.

Procedure:

- Stereotaxic Surgery:

- Anesthetize the mouse and secure it in the stereotaxic frame.

- Inject AAV-hSyn-GRABDA1m (e.g., 300-500 nL) into the target brain region (e.g., nucleus accumbens) using coordinates from a brain atlas.

- Implant an optical fiber cannula above the injection site.

- Allow 2-4 weeks for viral expression and recovery.

- Photometry Recording:

- Tether the mouse to the photometry system via a patch cord.

- Deliver 470 nm excitation light and collect emitted light (e.g., >500 nm).

- Simultaneously record behavioral video.

- Behavioral Paradigm:

- Conduct experiments such as Pavlovian conditioning (pairing a tone with a reward) or open field exploration.

- Data Processing:

- Demodulate the recorded signals to obtain 465 nm (sensor) and 405 nm (isosbestic control) channels.

- Fit the 405 nm signal to the 465 nm channel to generate a fitted baseline.

- Calculate ΔF/F = (465 nm signal - fitted baseline) / fitted baseline.

- Align dopamine signals (ΔF/F) with behavioral timestamps (e.g., cue onset, reward delivery).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A successful research program in this field relies on a core set of reagents and tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| cpGFP-based Dopamine Sensors (e.g., GRABDA, dLight series) | Core biosensor; fluorescence increases upon dopamine binding [1] [18]. | Monitoring real-time dopamine release in vivo. |

| Adeno-Associated Viral (AAV) Vectors | Gene delivery vehicle for sensor expression in specific brain regions [13]. | Targeted expression of GRABDA in mouse nucleus accumbens. |

| Cell-Type Specific Promoters (e.g., hSyn, Gfa) | Drives sensor expression in neurons or astrocytes, respectively [13]. | Restricting sensor expression to dopaminergic or excitatory neurons. |

| Fiber Photometry System | Optical setup for recording bulk fluorescence signals in freely moving animals [1]. | Recording mesolimbic dopamine dynamics during behavioral tasks. |

| Two-Photon Microscope | High-resolution imaging system for cellular/subcellular resolution [15]. | Imaging dopamine release at specific spines or axonal varicosities. |

| Dopamine Receptor Antagonists (e.g., Haloperidol) | Pharmacological blocker used to confirm sensor response is dopamine-specific [18]. | Control experiments to verify signal specificity in vitro and ex vivo. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core sensor architecture and a generalized workflow for sensor development and application.

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

Genetically encoded dopamine sensors have become indispensable in preclinical research, enabling discoveries in reward processing, motivation, and the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders.

Mechanistic Studies of Behavior: GRABDA and dLight sensors have been used to demonstrate that dopamine dynamics in the nucleus accumbens encode reward prediction error and are crucial for reinforcement learning [1]. Furthermore, they have revealed how drugs of abuse like heroin and cocaine hijack these natural dopamine signaling pathways, inducing long-lasting changes in circuit function [13].

Drug Discovery and Pharmacodynamics: These sensors provide a direct readout of drug efficacy on neural systems. For instance, they have been used to assess the addictive potential of ketamine by comparing its effects on dopamine release to those of known addictive substances like cocaine [13]. This application positions the sensors as powerful tools for screening novel therapeutic compounds and understanding their temporal effects on neuromodulation.

Future Directions: The field is rapidly advancing toward multiplexed imaging, where sensors of different colors (e.g., for dopamine and glutamate) are used simultaneously to dissect complex neurochemical interactions [20] [1]. Ongoing efforts focus on developing improved sensors with near-infrared fluorescence for deeper tissue penetration, as well as enhanced versions with greater sensitivity and specificity to uncover finer details of dopamine signaling in health and disease [1]. The recent development of a generalized grafting strategy for engineering neuropeptide sensors suggests that the principles honed in dopamine sensor development will continue to propel the creation of new tools for neuroscience [21].

The understanding of neuromodulatory signaling in the brain has been fundamentally transformed by the development of genetically encoded sensors. For decades, neuroscientists relied on techniques like fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) and microdialysis to study neurotransmitters, but these methods faced significant limitations in spatiotemporal resolution and molecular specificity [3] [23]. The advent of genetically encoded sensors for dopamine, particularly those based on G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), has enabled unprecedented observation of neuromodulator dynamics in living, behaving animals [8]. This technological breakthrough has led to the groundbreaking discovery that dopamine, and other neuromodulators like acetylcholine, propagate through the brain in rapid, wave-like patterns—overturning previous conceptions of slow, uniform signaling and revealing a previously hidden layer of complexity in neural communication [3].

The Sensor Revolution: From Calcium to Neuromodulators

The genetically encoded sensor revolution began with calcium indicators. GCaMP sensors, first developed in 2001, detect fluctuations in calcium concentration as a proxy for neuronal action potentials [3]. Their success motivated researchers to develop similar sensors for neurochemicals. In 2018, two teams independently described the first generation of high-performance dopamine sensors: dLight1 and GRAB-DA [3]. Both sensors were built by engineering a fluorescent protein into a dopamine receptor, creating a construct that changes its fluorescence intensity upon dopamine binding [8].

These GPCR-based sensors offer several critical advantages over previous methods:

- High Molecular Specificity: They can distinguish dopamine from similar molecules, a challenge for voltammetry [3] [8].

- Superior Temporal Resolution: They track dopamine release at subsecond timescales, capturing dynamics invisible to microdialysis [8].

- Genetic Targeting: They can be expressed in specific cell types or brain regions using viral vectors or transgenic animals [3].

- High Sensitivity: They detect dopamine at submicromolar to nanomolar concentrations, allowing measurement even in sparsely innervated brain regions [8].

Table: Key Genetically Encoded Dopamine Sensors

| Sensor Name | Key Characteristics | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| dLight1 [3] | Green fluorescent sensor; based on dopamine receptor; high sensitivity and specificity. | Monitoring phasic dopamine release in striatal regions. |

| GRAB-DA [3] | Green fluorescent sensor; high dynamic range and molecular specificity. | Detecting dopamine transients in various brain regions. |

| RdLight1 [8] | Red-shifted sensor; enables multiparametric imaging. | Experiments combining with other green-light-based sensors or optogenetics. |

| dLight3.8 [24] | Latest generation; substantially expanded dynamic range; enables fluorescence lifetime imaging. | Capturing the full amplitude and temporal complexity of dopamine signaling across brain regions. |

Revealing Dopamine Waves and Fast Neuromodulation

The Discovery of Dopamine Waves

The classical view suggested that when dopamine neurons were activated, the neuromodulator would be released uniformly across brain regions. This was overturned in the late 2010s when Arif Hamid and colleagues used the dLight sensor to track dopamine in the striatum of mouse brains [3]. Contrary to expectations, they discovered that dopamine was released in rapid, wave-like patterns [3]. This finding demonstrated that dopamine transmission carries information in a more complex and dynamic spatiotemporal pattern than previously imagined.

Fast Co-transmission of Dopamine and Acetylcholine

Building on the discovery of dopamine waves, Nicolas Tritsch's lab employed a dual-color imaging approach using GRAB-based sensors for both dopamine and acetylcholine. Their 2023 study revealed that both neuromodulators exhibit coordinated, sub-second fluctuations in the striatum [3]. Rather than maintaining stable baseline levels, their concentrations fluctuate with ultra-fast kinetics, suggesting these molecules interact to shape neural processing on a timescale much faster than traditionally thought [3].

Experimental Protocols for Key Discoveries

Protocol: Imaging Dopamine Waves In Vivo

This protocol outlines the key methodology used to discover wave-like dopamine propagation [3] [8].

1. Sensor Expression:

- Construct Delivery: Inject an adeno-associated virus (AAV) carrying the dLight1 gene under a synapsin promoter into the striatum of mice.

- Wait Period: Allow 3-6 weeks for robust sensor expression in neuronal tissue.

2. Surgical Preparation and Imaging:

- Cranial Window Implantation: For imaging, implant a chronic cranial window above the striatum.

- Fiber Photometry: Alternatively, for a simpler setup, stereotactically implant an optical fiber above the viral injection site.

- Head-Fixation: For superior optical stability, secure the animal's head under a two-photon microscope.

3. Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Stimulus Presentation: During imaging, present sensory stimuli or rewards known to evoke dopamine neuron activity.

- Fluorescence Recording: Record fluorescence changes (excitation: ~470 nm, emission: ~520 nm) at a high frame rate (>30 Hz).

- Wave Analysis: Process videos to extract fluorescence (ΔF/F) and apply motion correction. Use spatiotemporal correlation analysis to identify propagating wave fronts of dopamine release.

Protocol: Simultaneous Imaging of Dopamine and Acetylcholine Dynamics

This protocol describes the approach for revealing fast co-transmission [3].

1. Dual-Sensor Expression:

- Viral Co-injection: Co-inject two AAVs into the striatum: one expressing a green GRAB-DA sensor and another expressing a red GRAB-ACh sensor.

2. Two-Color Imaging:

- Microendoscope Setup: Use a head-mounted microendoscope (e.g., miniscope) equipped with dual LED light sources (e.g., 470 nm and 560 nm) and appropriate emission filters.

- Simultaneous Recording: Record fluorescence from both sensors simultaneously in freely behaving mice.

3. Cross-Correlation Analysis:

- Signal Processing: Calculate ΔF/F for each sensor's signal and filter to remove noise and slow drifts.

- Temporal Analysis: Perform cross-correlation analysis on the two processed time-series to quantify the sub-second temporal relationship between dopamine and acetylcholine transients.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

GPCR-Based Dopamine Sensor Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental working mechanism of dLight and GRAB sensors at the molecular level.

In Vivo Dopamine Imaging Workflow

This diagram outlines the complete experimental pipeline from sensor preparation to data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Dopamine Imaging

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| dLight Sensor Variants [8] [24] | Genetically encoded dopamine sensors with varying affinities (nM to μM range). | dLight1.3b for high-concentration regions (striatum); dLight3.8 for broad-spectrum detection. |

| GRAB-DA Sensors [3] [8] | Family of GPCR-based dopamine sensors with high specificity and rapid kinetics. | GRAB-DA1h for detecting subtle tonic changes; GRAB-DA2m for tracking phasic bursts. |

| AAV Delivery Vectors [8] | Adeno-associated viruses used to deliver sensor genes to specific brain regions. | AAV9-synapsin-dLight1.3b for neuronal-specific expression in cortex and striatum. |

| Fiber Photometry Systems [3] [8] | Systems using an implanted optical fiber to record bulk fluorescence in freely moving animals. | Measuring population-level dopamine dynamics in nucleus accumbens during reward learning. |

| Head-Mounted Microscopes [8] | Miniaturized microscopes (miniscopes) for cellular-resolution calcium or dopamine imaging. | Imaging dopamine release simultaneously with neuronal calcium activity in freely behaving mice. |

| Analysis Software | Custom and commercial software for processing fluorescence time-series data (e.g., Python, MATLAB). | Calculating ΔF/F, extracting transient kinetics, and correlating with behavioral timestamps. |

The discovery of dopamine waves and fast neuromodulation represents a paradigm shift in neuroscience, largely enabled by the precision of genetically encoded sensors. These tools have revealed that neuromodulatory transmission is far more dynamic and spatially organized than previously understood, operating on a sub-second timescale that directly shapes neural processing and behavior [3].

Future developments will focus on creating even more sensitive sensors like dLight3.8 [24], expanding the color palette for multiplexed imaging of multiple neurotransmitters simultaneously, and improving quantitative interpretation of sensor outputs [23]. As these tools continue to evolve, they will further illuminate the intricate chemical language of the brain, offering profound insights for understanding neural circuitry and developing novel therapeutics for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

From Bench to Behavior: Methodologies and Cutting-Edge Applications of Dopamine Sensors

In vivo imaging has revolutionized our capacity to decipher brain function by enabling real-time observation of neural activity in behaving animals. Central to this revolution are genetically encoded sensors, which convert specific neurochemical events into fluorescent signals, allowing researchers to track dynamics that were previously inaccessible [17]. For dopamine research in particular, these sensors have illuminated fundamental processes related to reward, motivation, and learning [3] [1]. When combined with optical recording techniques like fiber photometry and two-photon microscopy, they provide powerful platforms for investigating neurochemical signaling with high spatiotemporal precision. This application note details the principles, protocols, and practical considerations for implementing these complementary imaging modalities in the context of dopamine research, providing drug development professionals and neuroscientists with actionable methodologies for in vivo investigation.

Fiber Photometry: Monitoring Bulk Neurochemical Signals

Working Principle: Fiber photometry is a fiber-optic based technique that measures bulk fluorescence signals from genetically encoded sensors expressed in specific brain regions [25] [26]. The fundamental setup involves implanting an optical fiber into the brain of a freely moving animal to deliver excitation light and collect emitted fluorescence simultaneously [27]. The collected fluorescence is converted into electrical signals for analysis, providing a readout of neural activity or neurotransmitter dynamics [27].

For dopamine detection, the principle relies on GPCR-based sensors such as dLight or GRAB-DA, which embed a circularly-permuted green fluorescent protein (cpEGFP) into dopamine receptors [18] [1]. Upon dopamine binding, conformational changes in the receptor alter the fluorescence intensity of the cpEGFP, enabling real-time detection of dopamine transients with sub-second kinetics and nanomolar affinity [18].

Key Advantages: The primary strengths of fiber photometry include its compatibility with freely-moving behaviors, relatively low implementation cost, and ability to detect signals from deep brain structures with minimal tissue damage compared to microendoscopy approaches [26] [27]. It provides an excellent balance between temporal resolution and behavioral naturalism, particularly suited for correlating neurochemical dynamics with complex behaviors.

Two-Photon Microscopy: Cellular Resolution Imaging

Working Principle: Two-photon microscopy is a laser-scanning technique that uses near-infrared light for excitation, enabling imaging at greater depths with reduced scattering compared to single-photon methods [28] [27]. This technology leverages the simultaneous absorption of two photons for fluorophore excitation, which confines the excitation volume to a focal point, thereby minimizing photobleaching and photodamage [28]. This allows for long-term, high-resolution imaging of cellular and subcellular structures.

When applied to dopamine research, two-photon microscopy can track sensor fluorescence at single-cell or even dendritic spine resolution, revealing how specific neurons and microcircuits respond to dopamine release [28]. This is particularly valuable for understanding the spatial distribution of dopamine signals within complex brain regions.

Key Advantages: The exceptional spatial resolution of two-photon microscopy enables researchers to distinguish activity patterns across hundreds of neurons simultaneously while resolving subcellular structures [28]. The near-infrared excitation light penetrates tissue more effectively with less scattering, and the confined excitation volume minimizes tissue damage, facilitating long-term chronic imaging studies [28] [27].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Fiber Photometry and Two-Photon Microscopy

| Parameter | Fiber Photometry | Two-Photon Microscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Bulk signal (100s-1000s of neurons) [26] | Single cell to subcellular (μm) [28] |

| Temporal Resolution | Sub-second to milliseconds [18] | Typically 1-10 Hz (for field scanning) [28] |

| Imaging Depth | Limited by fiber placement, suitable for deep structures [29] | ~500 μm cortical depth, deeper with special approaches [29] |

| Behavioral Compatibility | Freely moving [26] | Head-fixed (with treadmills/VR) [29] [28] |

| Tissue Damage | Minimal from thin fiber [27] | Minimal scattering, but GRIN lenses cause damage [27] |

| Target Applications | Neurotransmitter dynamics during natural behaviors [25] [18] | Microcircuit analysis, structural plasticity [28] |

| Implementation Cost | Relatively low [25] | High (specialized laser systems) [27] |

Experimental Protocols for Dopamine Imaging

Sensor Selection and Expression

Choosing Dopamine Sensors: The selection of appropriate genetically encoded dopamine sensors is foundational to experimental success. Key sensor families include:

- GRAB-DA series: These GPCR-activation-based dopamine sensors offer high sensitivity (EC₅₀ from ~10 nM for DA1h to ~130 nM for DA1m) and large fluorescence changes (ΔF/F₀ ~90%) [18].

- dLight series: Similarly based on engineered dopamine receptors, these sensors provide variants with differing affinities suitable for detecting various concentration ranges of dopamine [3] [1].

Selection Criteria: Choose sensors based on affinity (high-affinity sensors for tonic dopamine, lower-affinity for phasic bursts), dynamic range (magnitude of fluorescence change), and kinetics (response speed) matched to your experimental questions [30] [1]. For multiplexing with other sensors or optogenetics, consider spectral variants with non-overlapping excitation/emission profiles.

Viral Delivery Protocol:

- Anesthetize the animal using appropriate anesthesia (e.g., isoflurane) and secure in a stereotaxic apparatus [27].

- Shave the scalp and make a midline incision to expose the skull [27].

- Level the skull by adjusting the stereotaxic apparatus to ensure bregma and lambda are in the same horizontal plane [27].

- Identify target coordinates relative to bregma using a brain atlas [27].

- Drill a small craniotomy (~1 mm diameter) at the target coordinates [27].

- Load purified viral vector (e.g., AAV-sensor) into a nanoliter injector [27].

- Lower the injection needle slowly to the target depth [27].

- Inject virus (200-500 nL total volume) at a slow, controlled rate (30-60 nL/min) to minimize tissue damage and allow for proper diffusion [27].

- Wait 5-10 minutes after injection before slowly retracting the needle to prevent backflow [27].

Surgical Implantation for Fiber Photometry

Fiber Implantation Protocol:

- Following virus injection, drill an additional hole for an anchoring skull screw [27].

- Secure the skull screw without penetrating the brain tissue [27].

- Position the fiber optic cannula (200-400 μm diameter) using a stereotaxic adapter and lower it to the target brain region [27].

- Apply a thin layer of dental acrylic to the skull, ensuring robust adhesion [27].

- Build a stable headcap by applying dental cement around the fiber implant and skull screw, leaving at least 4-5 mm of the ferrule exposed for future connection [27].

- Allow the cement to dry completely before carefully unscrewing the stereotaxic adapter [27].

- Administer post-operative analgesics and allow the animal to recover for at least 1-2 weeks for sensor expression and surgical recovery [27].

Imaging During Behavior

Fiber Photometry Recording:

- Connect the implanted fiber to the photometry system via a patch cord after the expression period [26].

- Habituate the animal to the tethering procedure in the experimental apparatus [29].

- Record a stable baseline fluorescence signal before behavioral testing [26].

- Synchronize fluorescence acquisition with behavioral monitoring using timestamps or TTL pulses [25] [26].

- Record throughout the behavioral session, which may include Pavlovian conditioning, operant tasks, or natural behaviors like social interactions [18] [1].

Two-Photon Imaging:

- Habituate animals extensively to head-fixation (typically 3-7 days) to minimize stress [29].

- Position the animal under the objective lens, using a treadmill or virtual reality system for behavioral engagement [28].

- Locate the expression region and identify cells or processes of interest [28].

- Acquire images at appropriate frame rates (typically 5-30 Hz for GCaMP) during behavioral tasks [28].

- Monitor animal behavior simultaneously with locomotion, pupil tracking, or lick monitoring [28].

The experimental workflow below illustrates the key decision points in establishing an in vivo dopamine imaging study.

Advanced Applications and Recent Innovations

Chemogenetic Sensitivity Tuning

A recent breakthrough in dopamine imaging involves chemogenetic approaches to modulate sensor sensitivity in real-time. Researchers have demonstrated that positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) selective for human dopamine D1 receptors can be used to boost the affinity of D1-based dopamine sensors without affecting endogenous mouse receptor function [30].

The compound DETQ has been shown to produce an ~8-fold leftward shift in the EC₅₀ of dLight1.3b, decreasing it from approximately 2 µM to 244 nM [30]. This creates a stable 31-minute window of enhanced sensitivity without apparent effects on animal behavior, enabling researchers to detect both tonic and phasic dopamine signaling within a single recording session [30]. This approach is particularly valuable for drug development applications where understanding concentration-dependent effects of compounds on dopamine signaling is crucial.

Multiplexed Imaging and Circuit Analysis

Advanced applications increasingly combine multiple sensors or integrate imaging with complementary techniques:

- Two-color imaging with spectrally distinct sensors allows simultaneous monitoring of dopamine and other neuromodulators like acetylcholine, revealing coordinated signaling patterns [3].

- Integration with optogenetics enables perturbation of specific pathways while monitoring dopamine release downstream, establishing causal relationships in neural circuits [26] [1].

- Combined fiber photometry and electrophysiology provides correlated measures of neurochemical release and electrical activity [26].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Dopamine Imaging

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Dopamine Sensors | GRAB-DA1h, GRAB-DA1m, dLight1.1, dLight1.3b [18] [1] | Genetically encoded indicators that fluoresce upon dopamine binding with varying affinities and kinetics |

| Control Sensors | DA1m-mut, DA1h-mut (C118A, S193N) [18] | Mutant sensors incapable of dopamine binding for controlling for motion artifacts and autofluorescence |

| Sensitivity Modulators | DETQ (D1-PAM) [30] | Positive allosteric modulator that temporarily increases dopamine sensor affinity for detecting low concentration signals |

| Viral Vectors | AAV-hSyn-GRAB-DA1m, AAV-CAG-dLight1.3b [18] [1] | Adeno-associated viruses for cell-type specific sensor expression in target brain regions |

| Reference Sensors | GCaMP (calcium), jRCaMP (red calcium) [29] [28] | Activity indicators for normalizing dopamine signals to neural activity or motion artifacts |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Signal Processing and Normalization

Preprocessing Steps:

- Demodulate signals if using alternating wavelengths (isosbestic control and sensor excitation) [25].

- Calculate ΔF/F by (F - F₀)/F₀, where F₀ represents baseline fluorescence [26].

- Remove motion artifacts and bleaching effects using high-pass filtering or polynomial fitting [25] [26].

- Align fluorescence traces with behavioral timestamps for trial-based or event-triggered averaging [26].

Signal Validation: Control experiments should include verification of specificity using receptor antagonists, assessment of photobleaching, and confirmation of signal linearity with appropriate physiological responses [25] [18]. The use of mutant control sensors (incapable of dopamine binding) helps distinguish specific dopamine signals from artifacts [18].

Analytical Approaches

For Fiber Photometry:

- Event-triggered averaging aligns fluorescence traces to specific behavioral events (e.g., lever presses, reward delivery) [26] [1].

- Trial classification compares dopamine dynamics across different trial types or behavioral outcomes [1].