Excitation and Inhibition in Sight: How Glutamate and GABA Shape the Visual Cortex's Response to Contrast

This article synthesizes current research on the dynamic roles of glutamate and GABA in the human visual cortex's response to varying image contrasts.

Excitation and Inhibition in Sight: How Glutamate and GABA Shape the Visual Cortex's Response to Contrast

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the dynamic roles of glutamate and GABA in the human visual cortex's response to varying image contrasts. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational neurochemistry, advanced methodological approaches like combined fMRI-MRS, and key challenges in interpreting neurotransmitter dynamics. We examine how the excitatory-inhibitory (E/I) balance, as probed by magnetic resonance spectroscopy, underpins neural specificity and contrast coding. The content further validates these principles through clinical correlations in visual pathologies like glaucoma and discusses the implications for developing targeted therapeutic strategies that modulate cortical E/I balance for treating visual processing disorders.

Neurochemical Foundations of Vision: How Glutamate and GABA Code for Image Contrast

Fundamental Neurobiology of Glutamate and GABA

In the mammalian central nervous system, neuronal communication is predominantly governed by the interplay between the primary excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate, and the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). These two neurotransmitters operate in a dynamic balance to regulate neural excitability, a process critical for all brain functions, from basic sensory processing to complex cognition [1] [2].

Glutamate is the most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain. Its release leads to the depolarization of postsynaptic neurons, facilitating the propagation of neural signals. Beyond its role in fast synaptic transmission, glutamate is integral to synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory consolidation [2]. However, precise regulation of extracellular glutamate is essential, as excessive levels can lead to excitotoxicity, a process of neuronal damage implicated in various neurological disorders [2].

GABA, synthesized directly from glutamate via the enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), serves the opposing inhibitory function. Activation of GABA receptors typically results in neuronal hyperpolarization, reducing the likelihood of action potential generation and dampening neural activity. This inhibition is crucial for preventing neuronal hyperactivity and maintaining network stability [3] [1].

The close metabolic relationship between glutamate and GABA creates a functional yin-and-yang balance. Their opposing actions allow for fine-tuning of neural circuit activity, ensuring that excitation and inhibition are properly balanced for optimal brain function [1] [4]. Disruptions in this excitation-inhibition (E/I) balance are linked to numerous pathologies, including epilepsy, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, and neurodegenerative diseases [3] [4] [2].

Receptor Subtypes and Signaling Mechanisms

Both glutamate and GABA exert their effects through multiple receptor classes with distinct signaling mechanisms.

Glutamate Receptors are divided into two major families:

- Ionotropic glutamate receptors are ligand-gated ion channels that mediate fast excitatory synaptic transmission. They are further classified into NMDA, AMPA, and kainate receptors, each with unique pharmacological and functional properties [2].

- Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) are G-protein coupled receptors that modulate synaptic activity through second messenger systems, leading to slower, longer-lasting modulatory effects [2].

GABA Receptors are classified into three main types:

- GABA-A receptors are ligand-gated chloride channels that mediate fast inhibitory postsynaptic potentials. They are heteropentameric structures assembled from various subunits, creating diverse receptor subtypes with distinct pharmacological profiles [3] [2].

- GABA-B receptors are G-protein coupled receptors that mediate slow and prolonged inhibitory effects through second messenger systems, affecting both pre- and postsynaptic sites [3].

- GABA-C receptors are primarily composed of ρ subunits and are mainly found in the retina, where they contribute to visual signal processing [3].

Table 1: Receptor Types for Glutamate and GABA

| Neurotransmitter | Receptor Class | Signaling Mechanism | Key Physiological Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate | Ionotropic (NMDA, AMPA, Kainate) | Ligand-gated cation channels | Fast excitatory synaptic transmission, synaptic plasticity |

| Metabotropic (mGluRs I, II, III) | G-protein coupled, second messengers | Modulation of synaptic transmission, neuronal excitability | |

| GABA | GABA-A | Ligand-gated chloride channels | Fast inhibitory synaptic transmission, hyperpolarization |

| GABA-B | G-protein coupled, second messengers | Slow inhibition, modulation of neurotransmitter release | |

| GABA-C (ρ) | Ligand-gated chloride channels | Retinal signal processing |

The Glutamate-GABA Balance in Visual Processing

The visual cortex provides an exemplary model system for investigating the functional interplay between glutamate and GABA. Research using advanced neuroimaging and spectroscopic techniques has revealed how the dynamics of these neurotransmitters underpin fundamental visual processes, including contrast response and binocular depth perception.

Neurotransmitter Dynamics Across Visual States

Functional magnetic resonance spectroscopy (fMRS) studies have quantified how GABA and glutamate levels change during different visual processing states. In a pivotal study examining the occipital cortex across three functional states, researchers observed contrasting dynamics between these neurotransmitters [5]:

- GABA levels decreased when participants opened their eyes in darkness compared to a baseline eyes-closed state

- Glutamate levels remained stable during eyes open in darkness but increased significantly during visual stimulation with a flickering checkerboard pattern [5]

These state-dependent neurotransmitter changes correlate with the amplitude of fMRI signal fluctuations, and importantly, visual discriminatory performance correlates specifically with GABA levels, but not glutamate levels [5]. This highlights the crucial role of inhibitory tone in shaping visual perception.

Table 2: Neurotransmitter Dynamics During Visual Processing

| Visual State | GABA Concentration | Glutamate/Glx Concentration | Functional Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eyes Closed (Baseline) | Baseline level | Baseline level | Baseline neural activity |

| Eyes Open (Darkness) | Decreased | Remains stable | Altered cortical excitability |

| Eyes Open (Visual Stimulation) | Further decrease (context-dependent) | Increased | Enhanced visual processing, correlates with BOLD signal |

Binocular Disparity Processing and E/I Balance

Recent research has specifically investigated how GABA and glutamate regulate the processing of binocular disparity, a fundamental cue for depth perception. The visual system must solve the "correspondence problem" - correctly matching features between the left and right eye's images while suppressing false matches [6].

A 2025 study measured GABA+ and Glx (glutamate-glutamine complex) concentrations in the human visual cortex during presentation of correlated (true depth cue) and anticorrelated (false depth cue) random dot stereograms. The findings revealed distinct patterns of neurotransmitter modulation across visual areas [6]:

- In the early visual cortex (EVC), correlated disparity increased Glx over anticorrelated and rest conditions

- In the lateral occipital cortex (LO), a ventral stream area important for object recognition, anticorrelated disparity decreased GABA+ and increased Glx

- The Glx/GABA+ ratio showed increased excitatory over inhibitory drive during anticorrelated disparity processing in LO [6]

These findings suggest that GABAergic inhibition contributes to the suppression of false matches in the ventral visual stream, a process essential for robust stereoscopic vision. The region-specific neurotransmitter dynamics illustrate how the E/I balance is differentially regulated across the visual hierarchy to support distinct computational goals.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Research on glutamate and GABA in visual processing employs sophisticated neuroimaging and electrophysiological techniques that allow for non-invasive measurement and manipulation of neurotransmitter systems in humans and animal models.

Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) Protocols

Functional MRS (fMRS) has emerged as a powerful method for quantifying neurotransmitter dynamics during visual processing. Typical experimental parameters from recent studies include [5] [6]:

- Voxel Placement: A 25×25×25 mm³ MRS voxel is carefully positioned in the visual cortex, aligned along the midline and rotated to avoid lipid signal contamination from the skull

- Acquisition Parameters: Studies commonly use MEGA-PRESS pulse sequences with TR/TE = 2000/68 ms, 256 single averages (128 edit-ON and 128 edit-OFF scans), bandwidth = 1200 Hz

- Experimental Design: Block designs comparing neurotransmitter levels across different visual conditions (e.g., eyes closed, eyes open in darkness, visual stimulation) with counterbalanced order

- Data Acquisition: MRS data are typically acquired before EPI sequences to avoid gradient-induced frequency drifts

For binocular disparity studies, specialized visual stimulation systems are employed:

- MRI-compatible stereoscopes for dichoptic presentation

- Random dot stereograms with correlated and anticorrelated disparity patterns

- Control conditions featuring blank gray screens with fixation crosses

These protocols enable researchers to quantify stimulus-dependent changes in GABA+ and Glx concentrations with sufficient temporal resolution to track neural events related to visual processing.

Electrophysiological Approaches

Historically, microelectrophoretic administration of neurotransmitters combined with single-unit recording has been used to study the effects of glutamate and GABA on visual neuronal responses. Foundational studies in cat visual cortex demonstrated that [7]:

- Glutamate application enlarges receptive field sizes and increases response amplitudes within the receptive field

- GABA application decreases neuronal excitability, potentially leading to complete response blockade

- In some cases, glutamate can indirectly inhibit certain cells, likely through activation of local inhibitory interneurons

These classic approaches continue to inform modern research by providing cellular-level insights into neurotransmitter effects on specific response properties of visual neurons.

Molecular Crosstalk and Homeostatic Regulation

Recent discoveries have revealed unexpected molecular interactions between the glutamatergic and GABAergic systems that blur the traditional distinction between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission.

Direct Glutamate Modulation of GABA-A Receptors

A groundbreaking 2022 study identified a novel allosteric glutamate-binding site on GABA-A receptors, demonstrating that glutamate can directly potentiate GABA-evoked currents [4]. This crosstalk exhibits several remarkable characteristics:

- Mechanism: Glutamate binds at a novel site located at the α+/β- subunit interface of the GABA-A receptor, distinct from the GABA binding site

- Potency: The EC₅₀ of glutamate potentiation is approximately 180 μM, with the lowest effective dose around 30 μM

- Subunit Dependence: The potentiation does not require the γ subunit; in fact, the presence of the γ subunit significantly reduces glutamate potency

- Physiological Impact: Genetic impairment of this glutamate potentiation in knock-in mice resulted in increased neuronal excitability, decreased thresholds to noxious stimuli, and increased seizure susceptibility [4]

This direct interaction represents a rapid homeostatic feedback mechanism where the excitatory neurotransmitter can immediately enhance inhibitory transmission to maintain E/I balance.

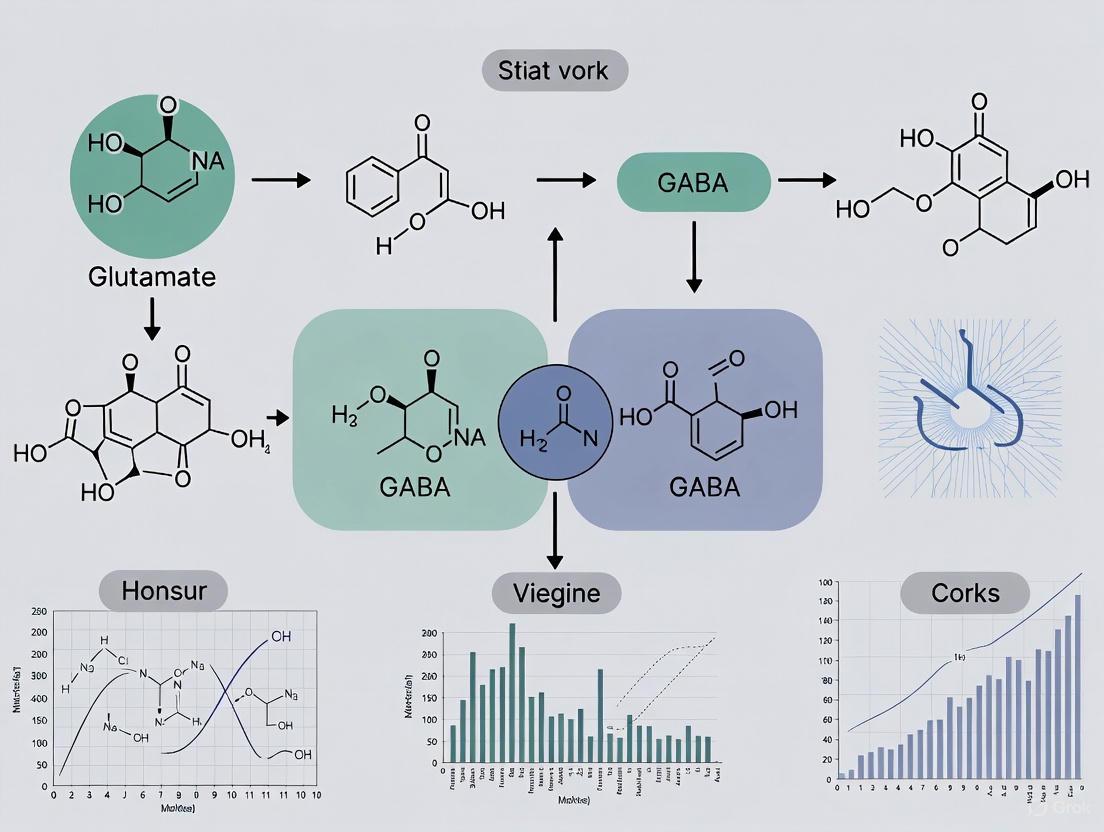

Diagram 1: Molecular crosstalk between glutamate and GABA-A receptors. Glutamate binds to a novel allosteric site on GABA-A receptors, potentiating GABA-evoked chloride influx and enhancing neuronal inhibition. This mechanism provides rapid homeostatic regulation of excitation-inhibition (E/I) balance [4].

Research Reagents and Methodological Toolkit

Studies investigating glutamate and GABA in visual processing rely on specialized research reagents and methodological approaches.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Tools | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| GABAergic Agents | Bicuculline, Gabazine | GABA-A receptor antagonism | Blocking fast inhibitory transmission |

| Muscimol, Isoguvacine | GABA-A receptor agonism | Enhancing inhibitory tone | |

| Baclofen | GABA-B receptor activation | Modulating slow inhibition | |

| Glutamatergic Agents | NMDA, AMPA, Kainate | Receptor subtype activation | Selective excitation |

| CNQX, AP5 | Receptor subtype blockade | Isolating receptor contributions | |

| Enzyme Markers | Anti-GAD antibodies | GABAergic neuron identification | Labeling GABA synthesis enzyme |

| Anti-GDH antibodies | Glutamatergic activity mapping | Visualizing glutamate metabolism | |

| Methodological Approaches | fMRS (MEGA-PRESS) | In vivo neurotransmitter quantification | Measuring GABA+ and Glx dynamics |

| Microelectrophoresis | Cellular-level drug application | Precise receptor manipulation | |

| Binocular stereoscopes | Dichoptic visual stimulation | Presenting disparity cues |

Visual Processing Workflow and Neurotransmitter Dynamics

The following diagram integrates the experimental workflow and neurotransmitter dynamics in visual processing research:

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow in visual processing research. Different visual stimuli engage distinct processing mechanisms across the visual hierarchy, resulting in region-specific neurotransmitter dynamics measurable with fMRS, which ultimately correlate with behavioral performance [5] [6].

The intricate interplay between glutamate and GABA forms the fundamental neurochemical basis for visual processing in the cerebral cortex. The E/I balance maintained by these neurotransmitters enables the precise neural computations required for contrast response, binocular disparity processing, and ultimately, visual perception. Advanced neuroimaging techniques, particularly fMRS, have revealed that these neurotransmitters exhibit dynamic, state-dependent changes across different visual areas, reflecting their specialized roles in the visual processing hierarchy. Furthermore, the recently discovered direct molecular crosstalk between glutamate and GABA-A receptors adds a new layer of complexity to our understanding of how E/I balance is rapidly regulated at the synaptic level. Continuing research on these mechanisms promises to advance not only our fundamental knowledge of visual neuroscience but also our understanding of various neurological and psychiatric disorders where E/I balance is disrupted.

The contrast response function (CRF) describes how neural activity in the visual system changes in response to variations in stimulus contrast, serving as a fundamental bridge between visual perception and its underlying neural mechanisms. Understanding the CRF provides critical insights into how the brain transforms physical light patterns into conscious visual experience. Research over recent decades has established that this transformation involves complex interactions between hemodynamic responses, excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission, and hierarchical cortical processing.

This technical review examines the CRF through the lens of neurochemical signaling, particularly focusing on the roles of the primary excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters glutamate and GABA. We synthesize evidence from advanced neuroimaging techniques, including functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), and computational modeling, to present a comprehensive framework of how contrast information is processed across the visual hierarchy. The balance between glutamate and GABA signaling appears crucial for shaping contrast-dependent neural responses and maintaining the exquisite sensitivity of visual processing across varying stimulus conditions.

Neurochemical Foundations of Contrast Processing

Glutamate and GABA Dynamics During Visual Stimulation

The interplay between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission forms the neurochemical basis for contrast processing in the visual cortex. Simultaneous measurement of BOLD-fMRI and neurochemical concentrations using MR spectroscopy at 7 Tesla has revealed distinct response patterns for glutamate and GABA across different contrast levels.

Table 1: Neurochemical Responses to Varying Image Contrasts in Human V1

| Contrast Level | Glutamate Response | GABA Response | BOLD Signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3% | No significant change | Steady | Linear increase |

| 12.5% | No significant change | Steady | Linear increase |

| 50% | No significant change | Steady | Linear increase |

| 100% | Significant increase | Steady | Linear increase |

As illustrated in Table 1, glutamate concentrations show a significant increase only at the highest contrast level (100%), while GABA levels remain steady across all contrast intensities [8]. This suggests that excitatory neurotransmission has a higher activation threshold compared to the hemodynamic response measured by BOLD fMRI, which increases linearly with contrast. The dissociation between neurochemical and hemodynamic responses at lower contrast levels indicates a potential sensitivity threshold for detecting glutamate changes during visual processing.

The temporal dynamics between these neurotransmitter systems are equally important. Research has demonstrated that in the visual cortex, GABA and Glx (glutamate-glutamine complex) concentrations drift in opposite directions during rest, with GABA decreasing and Glx increasing over time [9]. Furthermore, GABA concentrations predict subsequent opposite changes in Glx approximately 120 seconds later, revealing a dynamic interplay between excitation and inhibition that may optimize contrast sensitivity.

Metabolic Demands of Contrast Processing

The relationship between neurochemical signaling and energy metabolism presents a complex picture of contrast processing. The BOLD response reflects a composite measure of blood flow, blood volume, and oxygen demand resulting from neuronal activity energy requirements [8]. Both excitatory and inhibitory signaling consume energy, leading to increased local BOLD signals, making the interpretation of BOLD responses ambiguous without complementary neurochemical measures.

The MRS-visible glutamate signal comprises both the neurotransmitter pool and glutamate involved in energy metabolism, necessitating careful interpretation of functional MRS studies [8]. This dual role of glutamate in both neurotransmission and metabolism highlights the intricate relationship between information processing and energy utilization in contrast coding.

Neural Contrast Response Functions Across Cortical Areas

Hierarchical Processing of Contrast Information

The visual system processes contrast information through a distributed network of cortical areas, each with distinct response properties. Research using Relational Neural Control (RNC) has revealed systematic changes in how contrast information is represented across the visual hierarchy [10].

Table 2: Representational Relationships Across Visual Cortical Areas

| Cortical Area Comparison | Representational Alignment | Representational Disentanglement | Hierarchical Distance Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| V1 vs. V2 | High | Low | Small effect |

| V1 vs. V3 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate effect |

| V1 vs. V4 | Low | High | Large effect |

| V2 vs. V3 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate effect |

| V2 vs. V4 | Low | High | Large effect |

| V3 vs. V4 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate effect |

As shown in Table 2, representational alignment decreases while disentanglement increases with stepwise distance between visual areas in the processing hierarchy [10]. This indicates that visual areas further apart in the processing hierarchy share less representational content, reflecting their specialized roles in contrast and form processing.

The neural contrast sensitivity function (nCSF) approach has further elucidated how different cortical locations respond to varying combinations of contrast and spatial frequency. This method has demonstrated systematic variations in nCSF properties according to eccentricity and position in the visual hierarchy, with the peak spatial frequency that a cortical location responds to decreasing with eccentricity and across the visual hierarchy [11].

Center-Surround Interactions in Contrast Processing

Contrast processing involves not only responses to local stimulus features but also complex interactions between center and surround regions. The Stabilized Supralinear Network (SSN) model effectively explains several key phenomena of surround suppression in V1, where responses to a center stimulus are modulated by surrounding stimuli [12].

The SSN model accounts for three crucial features of surround suppression:

- Suppression of both inhibitory and excitatory currents received by a cell

- Strongest suppression when surround orientation matches the center stimulus

- Feature-specific suppression of plaid components matching the surround orientation

These center-surround interactions reflect sophisticated computational mechanisms that enhance contrast discrimination and optimize visual processing for natural scenes, where contextual information plays a crucial role in perception.

Methodological Approaches for Assessing Contrast Responses

Combined fMRI-MRS Protocol

The simultaneous acquisition of fMRI and MRS data provides a powerful approach for investigating the relationship between hemodynamic responses and neurochemical dynamics during contrast processing.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for combined fMRI-MRS studies of contrast response functions

Key Experimental Parameters:

- Magnetic Field Strength: 7 Tesla for improved signal-to-noise ratio

- MRS Voxel: 8 cm³ positioned in occipital lobe, centered on calcarine sulcus

- Visual Stimuli: Contrast-reversing checkerboards (8 Hz) at four contrast levels

- Stimulation Protocol: Block design with 64 s baseline and 64 s stimulation

- MRS Sequence: Short-echo semi-LASER (TE = 36 ms, TR = 4 s) with VAPOR water suppression

This protocol enables the correlation of BOLD signal changes with dynamic alterations in glutamate and GABA concentrations, providing insights into the neurochemical underpinnings of contrast processing [8].

Population Receptive Field (pRF) Mapping with Contrast Variation

Traditional pRF mapping uses single high-contrast stimuli to identify visual field representations in the cortex. Recent advances have incorporated varying contrast levels to measure contrast sensitivity across the visual field without requiring precise fixation, making the method suitable for patients with visual impairments [13].

The enhanced pRF approach incorporates:

- Large-field stimulation (40° diameter) covering central and peripheral vision

- Multiple contrast levels to characterize subtle sensitivity changes

- Structural retinotopic atlas as an alternative when pRF mapping is infeasible

- Model-based analysis to estimate contrast sensitivity at each visual field location

This method has successfully characterized known sensitivity differences across eccentricities and visual quadrants, demonstrating greater sensitivity in V1 regions receiving input from horizontal versus vertical quadrants and lower versus upper quadrants [13].

Neural Contrast Sensitivity Function (nCSF) Modeling

The nCSF approach models how neuronal populations respond to contrast as a function of spatial frequency, providing a neural equivalent of the behavioral contrast sensitivity function.

Experimental Protocol:

- Stimuli: Static sinewave gratings with systematic variation in contrast (0.25-80%) and spatial frequency (0.5-18 c/deg)

- Design: Blocked presentation with increasing and decreasing contrast sequences

- Analysis: Asymmetric parabolic function to model nCSF, with CRF modeling the transition from no response to full response

- Validation: Parameter recovery simulations and comparison with known cortical organizational principles

This method has shown that nCSF properties vary systematically with eccentricity, polar angle, and across the visual hierarchy, providing a quantitative framework for assessing neural contrast sensitivity in both healthy and clinical populations [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Methods for Contrast Response Research

| Research Tool | Specifications & Purpose | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| High-Field MRI | 7T Siemens scanner with 32-channel head coil; enhances signal-to-noise for fMRI and MRS | Provides high-resolution BOLD and neurochemical data [8] |

| MRS Sequence | Short-echo semi-LASER (TE=36ms); optimizes detection of neurometabolites | Quantifies glutamate and GABA concentrations during visual stimulation [8] |

| Visual Stimulation System | Gamma-linearized projector with PsychToolbox; precise contrast control | Presents contrast-varying stimuli (3-100% Michelson contrast) [8] [11] |

| Dielectric Pad | BaTiO₃/deuterated water suspension; improves transmit field efficiency | Enhances signal quality in occipital cortex [8] |

| Encoding Models | Deep-neural-network-based models; predict fMRI responses from visual features | Generates in silico fMRI responses for large image sets [10] |

| Stabilized Supralinear Network Model | Biologically-constrained computational model; simulates V1 circuit dynamics | Explains center-surround interactions and contrast normalization [12] |

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

The research methodologies and findings described herein have significant implications for understanding and diagnosing visual disorders. Abnormalities in contrast processing characterize numerous ophthalmological and neurological conditions, including amblyopia, glaucoma, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson's disease [11]. The development of non-invasive methods to assess neural contrast sensitivity offers promising avenues for early detection and monitoring of these conditions.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Translating nCSF methods to clinical populations with various visual impairments

- Investigating pharmacological manipulations of GABA and glutamate systems on contrast processing

- Developing integrated models that incorporate neurochemical, hemodynamic, and perceptual aspects of contrast coding

- Exploring developmental trajectories of contrast response functions across the lifespan

- Linking individual differences in neurochemical balances to contrast perception abilities

The continued refinement of methods for assessing the contrast response function will enhance our understanding of visual processing and provide valuable tools for diagnosing and monitoring visual disorders, ultimately contributing to the development of targeted therapeutic interventions.

In the neural circuitry of the visual cortex, the balance between excitatory and inhibitory signaling is paramount for processing visual information. Glutamate, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter, and GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, engage in a dynamic interplay that governs neuronal responses to sensory input. A fundamental question in visual neuroscience is determining the precise stimulus intensity at which glutamate-mediated signaling transitions from being negligible to functionally significant. This threshold dictates how the cortex encodes contrast, forms representations of the visual world, and maintains stability against runaway excitation. Framed within broader research on cortical contrast response, this review synthesizes current findings on the neurochemical and perceptual thresholds of glutamate signaling, detailing the experimental methodologies that enable their quantification and the theoretical models that explain their underlying logic.

Neurochemical Foundations of Contrast Response

The response of the visual cortex to varying stimulus intensities is not linear. At the neurochemical level, this is reflected in the dynamic concentrations of glutamate and GABA, which can be measured in vivo using Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS). A key concept in understanding contrast perception is the "dipper function"—a non-linear relationship where the detection of a contrast increment is actually facilitated (threshold is lowered) by the presence of a low-contrast "pedestal" stimulus, before becoming harder again at higher pedestal contrasts [14].

The dipper function is formally quantified as the difference between the absolute contrast threshold (C0) and the minimum increment threshold (Cmin), divided by the maximum threshold (Cmax): DM = (C0 - Cmin) / Cmax [14]. Research has shown that the strength of this dipper effect is strongly correlated with GABA concentration in the visual cortex [14]. Higher GABA levels are associated with a more pronounced dipper function, indicating that inhibition plays a critical role in this fundamental perceptual non-linearity.

Table 1: Key Neurochemical and Perceptual Metrics in Contrast Response

| Metric | Description | Relationship to GABA/Glutamate | Experimental Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dipper Magnitude (DM) | Strength of facilitation at low contrast pedestals [14] | Positively correlated with GABA concentration [14] | Contrast discrimination task |

| Contrast Detection Threshold (C0) | Minimum contrast to detect a stimulus [14] | Inversely related to GABA; high GABA reduces neural noise, potentially lowering C0 [14] | 2-alternative forced choice (2AFC) task |

| Glx/GABA+ Ratio | Balance of excitatory to inhibitory neurochemical drive [15] | Increased during visual stimulation (e.g., correlated disparity); signifies excitatory drive [15] | Functional Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (fMRS) |

| Neural Variability (SDBOLD) | Moment-to-moment BOLD signal fluctuation [16] | Modulation by stimulus complexity is GABA-dependent; follows an inverted-U relationship [16] | fMRI time-series analysis |

Beyond baseline states, visual stimulation induces rapid, region-specific neurochemical shifts. A 2025 fMRSI (functional Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging) study demonstrated that visual stimulation produces distinct spatial maps of GABA and glutamate (Glu) responses, with Glu increases observed in the visual cortex and GABA increases in both the thalamus and visual cortex [17]. Furthermore, the specific visual feature being processed dictates the neurochemical response. For instance, viewing correlated binocular disparity (a valid depth cue) in the early visual cortex (EVC) increases Glx levels compared to a rest condition [15]. In the higher-level lateral occipital cortex (LO), viewing anticorrelated disparity (a false depth cue) decreases GABA+ and increases Glx, shifting the Glx/GABA+ ratio toward excitation [15]. This suggests a flexible, feature-specific mechanism for regulating the excitatory-inhibitory balance.

Quantifying Thresholds: From Perception to Neurochemistry

The GABAergic Regulation of Perceptual Thresholds

The link between GABA concentration and perceptual thresholds is mechanistic, not merely correlative. Computational modeling using the Wilson-Cowan framework—a classic model comprising interacting excitatory and inhibitory neural populations—indicates that GABA's role implements a form of suppressive gain control [14]. Higher GABAergic inhibition has a dual effect:

- Reducing intrinsic neural noise, which can improve signal detection at near-threshold contrasts.

- Reducing neural response gain, which paradoxically can decrease neural sensitivity to high-contrast stimuli while improving perceptual discrimination [14].

This gain control mechanism is crucial for aligning the brain's dynamic range with the statistics of sensory input. The importance of GABA is further highlighted by pharmacological and aging studies. Administering lorazepam, a GABAA receptor agonist, alters how neural variability (SDBOLD) scales with stimulus complexity. Its effect follows an inverted-U function: individuals with lower baseline GABA levels show a drug-related increase in variability modulation, while those with higher baseline GABA show no change or a reduction [16]. As older adults typically have lower visual cortex GABA levels, they also exhibit a reduced ability to modulate neural variability in response to complex stimuli, which is linked to poorer visual discrimination performance [16].

Temporal Dynamics of Glutamate and GABA

The threshold for significant glutamate signaling is not static but fluctuates over time. MRS studies reveal a temporal interdependency between the two neurotransmitters during rest. In the visual cortex, GABA+ and Glx concentrations drift in opposite directions over time, with GABA+ decreasing and Glx increasing [9]. Crucially, a change in GABA+ concentration predicts an opposite change in Glx approximately 120 seconds later [9]. This predictive relationship is region-specific, being absent in the posterior cingulate cortex, and suggests a homeostatic feedback loop where inhibition proactively gates subsequent excitation in the visual system [9].

Table 2: Neurochemical Responses to Visual Stimulation Across Cortical Areas

| Visual Cortex Area | Stimulus Type | GABA Response | Glutamate/Glx Response | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Visual Cortex (EVC) [15] | Correlated Binocular Disparity | No significant change | Increase over anticorrelated and rest | Enhances processing of valid depth signals |

| Lateral Occipital Cortex (LO) [15] | Anticorrelated Binocular Disparity | Decrease | Increase | Suppression of invalid depth cues; shift to excitatory drive |

| Visual Cortex (General) [17] | Broad Visual Stimulation | Increase (in visual cortex & thalamus) | Increase (in visual cortex) | Coordinated excitatory signaling and localized inhibition |

| Visual Cortex (at rest) [9] | No stimulation (Eyes closed) | Gradual decrease over time | Gradual increase over time | Underlying homeostatic balance between systems |

Experimental Protocols for Probing Neurochemical Thresholds

Functional Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (fMRS)

Purpose: To measure dynamic changes in neurometabolite concentrations (e.g., GABA and Glx) in the human brain during controlled visual stimulation [17] [15]. Workflow:

- Voxel Placement: A spectroscopic voxel is positioned over the target visual area (e.g., early visual cortex EVC or lateral occipital complex LOC) using anatomical scans [15].

- Stimulus Presentation: Participants are presented with block-designed conditions within the MRI scanner. For disparity studies, conditions include correlated disparity, anticorrelated disparity, and a rest condition (blank gray screen with fixation) [15].

- Data Acquisition: Spectra are acquired using a MEGA-PRESS sequence, an editing sequence that isolates the GABA signal from overlapping metabolites. A typical protocol uses: TE = 68 ms, TR = 3000 ms, and 256 transients [9].

- Quantification: Acquired spectra are fitted to estimate the concentration of GABA+ (including macromolecules) and Glx, often referenced to the internal water signal or creatine. Concentrations are compared across stimulus conditions to identify task-evoked neurochemical changes [15].

Contrast Discrimination Task with Psychophysical Modeling

Purpose: To behaviorally measure contrast detection thresholds and relate them to individual differences in visual cortex GABA concentration [14]. Workflow:

- Stimuli: Participants view two sinusoidal grating patches presented on either side of a fixation point [14].

- Task Procedure: In a two-alternative forced-choice (2AFC) design, participants identify which patch has the higher contrast. One grating serves as the "pedestal" (base contrast), and the other is the pedestal plus a contrast increment [14].

- Threshold Estimation: An adaptive staircase procedure (e.g., QUEST) is used across multiple blocks with different pedestal contrasts (e.g., 0 to 0.4) to estimate the contrast increment required for 82% correct performance at each pedestal level [14].

- Model Fitting: The resulting "dipper function" (threshold vs. pedestal contrast) is fit with a sigmoidal Contrast Response Function (CRF) or the Wilson-Cowan neural population model. Model parameters (e.g., suppression strength, response criterion) are then correlated with MRS-derived GABA levels [14].

Molecular Logic of Synaptic Signaling

The response of a neuron to glutamatergic input is fundamentally determined by the molecular composition of its postsynaptic density. Super-resolution proteometric imaging of individual synapses in the mouse neocortex reveals that glutamatergic synapses are not uniform but cluster into distinct subclasses based on their glutamate receptor content [18]. These subclasses appear to define a functional logic:

- Large, AMPAR-rich synapses are thought to represent potentiated, high-efficacy connections that strongly transmit excitatory signals.

- Small, NMDAR-rich "silent" synapses contain NMDA receptors but lack detectable AMPA receptors. These synapses are inefficient at driving the postsynaptic neuron under baseline conditions but are primed for plasticity [18].

Crucially, the ultrastructural features of a synapse (e.g., spine head size, neck diameter) are a better predictor of its receptor content than the identity of its parent neuron [18]. This suggests that the threshold for significant glutamate signaling is set at the level of the individual synapse, with its specific proteometric profile determining its contribution to network activity.

Visual Stimulus to Perception Pathway: This diagram illustrates the pathway from visual contrast input to perceptual outcome, highlighting the opposing roles of glutamatergic (excitatory) and GABAergic (inhibitory) signaling in shaping the stimulus intensity threshold.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Methodologies

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MEGA-PRESS MRS [9] | Isolates and quantifies in vivo concentrations of GABA+ and Glx from a brain voxel. | Measuring neurochemical dynamics during rest or visual stimulation tasks. |

| fMRSI (functional MRSI) [17] | Generates high-resolution spatio-temporal maps of neurotransmitter changes across the brain. | Localizing GABA and Glu responses to specific visual areas (e.g., V1, thalamus) during stimulation. |

| AAV-CaMKIIα-ChR2/eArch3.0 [19] | Enables optogenetic activation (ChR2) or inhibition (eArch) of glutamatergic neurons in animal models. | Causally testing the role of specific neuronal populations (e.g., V2M glutamatergic neurons) in pain and perception. |

| GABAA Agonist (e.g., Lorazepam) [16] | Pharmacologically enhances GABAergic inhibition in the human brain. | Causally probing the role of GABA in perceptual tasks and neural variability. |

| Wilson-Cowan Model [14] | A biophysical model of interacting excitatory and inhibitory neural populations. | Simulating and interpreting the effects of GABA and glutamate on contrast response functions. |

| Array Tomography [18] | Multiplex super-resolution imaging of synaptic proteins in ultrastructural context. | Classifying synapse subtypes and quantifying receptor content (e.g., AMPA/NMDA ratio) at single-synapse level. |

Determining the threshold at which glutamate signaling becomes significant reveals a core operating principle of the visual cortex: excitation is granted significance only through its dynamic regulation by inhibition. The threshold is not a fixed value but a fluid interface, shaped by the immediate sensory environment, the internal neurochemical state, and the historical pattern of activity that has shaped synaptic micro-architecture. GABAergic suppression of neural noise and gain establishes the baseline against which glutamatergic signals must compete, a relationship quantified by the non-linear dipper function in contrast perception. The development of high-resolution fMRSI and single-synapse proteometry is transforming our understanding, showing that these thresholds are set locally within specialized synaptic circuits and are modulated over time by predictive neurochemical interactions. This refined understanding of excitatory-inhibitory balance provides a critical foundation for developing therapeutic strategies for neurological disorders where this balance is disrupted, from neuropathic pain to psychiatric conditions.

GABA's Role in Maintaining Neural Specificity and Stabilizing Baseline Activity

This technical review examines the critical role of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in regulating neural specificity and stabilizing baseline activity in the visual cortex, with implications for therapeutic development. GABAergic inhibition serves as a fundamental mechanism for sharpening neuronal response properties, maintaining excitation-inhibition balance, and optimizing sensory processing. We synthesize recent human and animal studies demonstrating that GABA levels directly predict neural specificity metrics and that GABA decline leads to degraded sensory representations. The intricate crosstalk between GABA and glutamate receptors reveals sophisticated homeostatic regulation of cortical circuits. For researchers and drug development professionals, this review provides validated experimental protocols, key reagent solutions, and emerging targets for modulating GABAergic function to restore neural processing fidelity in neurological disorders.

In the visual cortex, neural specificity refers to the precise and distinct response patterns of neuronal populations to different visual features, a fundamental property enabling efficient sensory and cognitive functions. This specificity is dynamically shaped by GABAergic inhibition, which sharpens neuronal tuning and reduces response confusability. The balance between glutamatergic excitation and GABAergic inhibition (E/I balance) constitutes a core mechanism governing visual processing, from basic contrast detection to complex pattern recognition. Recent research framed within visual cortex contrast response studies demonstrates that GABA plays a particularly crucial role in maintaining neural specificity by preventing the overlapping representations of different visual stimuli, thereby ensuring efficient encoding of visual information. When this GABAergic regulation falters, as occurs in aging and neurodegenerative conditions, the resulting degradation of neural specificity manifests as measurable impairments in visual perception and cognition.

Mechanisms of GABAergic Regulation of Neural Specificity

Sharpening Neural Response Profiles

GABAergic inhibition enhances neural specificity through multiple complementary mechanisms that collectively sharpen neuronal response profiles:

Contrast Normalization: In primary visual cortex (V1), GABA-mediated inhibition implements a normalization mechanism where responses to chromatic and achromatic stimuli become interdependent. This normalization effect optimally adjusts the dynamic range of neuronal responses to varying contrast levels, with GABA acting as a key implementation signal [20] [21].

Feature Selectivity: GABAergic interneurons sharpen the selectivity of visual neurons for specific stimulus features by suppressing responses to non-preferred features. This lateral inhibition creates more distinct neural population responses to different visual categories, effectively reducing pattern confusability [22].

Temporal Precision: By controlling the timing and duration of excitatory responses, GABAergic signaling ensures that visual information is processed with millisecond precision, preventing the temporal blurring of successive visual inputs that would degrade motion perception and dynamic scene analysis.

Regulating Neural Variability and Signal-to-Noise

Moment-to-moment neural variability in the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal scales with stimulus complexity, and GABA serves as a critical regulator of this variability modulation:

Higher baseline GABA levels in the visual cortex enable greater modulation of neural variability in response to increasingly complex stimuli. This variability modulation capacity is significantly reduced in older adults with lower GABA concentrations, resulting in compromised visual discrimination performance [16]. The relationship follows an inverted-U function, where pharmacologically increasing GABA activity with benzodiazepines boosts variability modulation in individuals with low baseline GABA, but has reduced effects or even slightly impairs it in those with already high GABA levels.

Molecular Crosstalk Mechanisms

The traditional view of separate excitatory (glutamate) and inhibitory (GABA) systems has been challenged by discoveries of direct molecular crosstalk:

Allosteric Glutamate Binding to GABAA Receptors: Glutamate directly binds to a novel allosteric site on GABAA receptors at the α+/β− subunit interface, potentiating GABA-evoked currents. This potentiation does not require γ subunits and is actually reduced in their presence. In HEK293 cells expressing recombinant α1β2 GABAA receptors, glutamate (EC50 ≈ 180 μM) potentiated GABA-evoked currents by over 3-fold, primarily by increasing GABA binding affinity (reducing EC50 from 13.19 μM to 5.46 μM) [4].

Co-transmission and Co-release: Many neurons co-release glutamate and GABA from the same synaptic terminals, often from different synaptic vesicles with distinct release properties. At supramammillary nucleus (SuM) to dentate gyrus synapses, glutamate and GABA are co-released from different vesicle populations, exhibiting different paired-pulse ratios, calcium sensitivities, and short-term plasticity profiles [23].

Homeostatic Regulation of Neuronal Excitability

The newly discovered glutamate-GABAA receptor interaction represents a rapid feedback mechanism for homeostatically regulating neuronal excitation:

Genetic impairment of this glutamate potentiation in knock-in mice results in increased neuronal excitability phenotypes, including decreased thresholds to noxious stimuli and enhanced seizure susceptibility, demonstrating its critical role in maintaining excitation-inhibition balance [4].

Quantitative Evidence: GABA, Neural Specificity, and Behavior

GABA Levels Predict Neural Specificity and Behavioral Performance

Table 1: Quantitative Relationships Between GABA Levels and Functional Measures

| Brain Region | GABA Measure | Functional Correlation | Effect Size | Population | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Cortex | GABA+ (MRS) | Neural specificity (fMRI) | β = 0.337, p = 0.020 | Glaucoma patients | [22] |

| Visual Cortex | GABA+ (MRS) | Variability modulation (ΔSDBOLD) | Inverted-U function | Young vs. older adults | [16] |

| Motor Cortex | GABA/NAA ratio | Reaction time | r = 0.572, p = 0.0001 | Subarachnoid hemorrhage | [24] |

| Frontal Cortex | GABA+/Cr (MRS) | Cognitive performance | Stabilization in oldest-old | Cognitively-intact >85yo | [25] |

Multiple studies demonstrate that GABA levels quantitatively predict neural function and behavioral performance. In glaucoma patients, visual cortex GABA levels decrease with disease severity, and this reduction specifically predicts degraded neural specificity independent of age or retinal structural damage [22]. The association remains significant after controlling for age, gray matter volume, and retinal impairments, suggesting a specific role for GABA in maintaining distinct neural representations.

Aging and Neurodegenerative Conditions

Age-related GABA decline contributes significantly to degraded neural processing, though this relationship may stabilize in the cognitively-intact oldest-old:

Table 2: GABA Alterations in Aging and Neurological Conditions

| Condition | GABA Change | Neural Specificity Impact | Behavioral Manifestation | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Aging | Gradual reduction | Reduced variability modulation | Poorer visual discrimination | [16] |

| Glaucoma | Severity-dependent decrease | Degraded visual cortex specificity | Visual cognitive impairments | [22] |

| Subarachnoid Hemorrhage | Left motor cortex reduction | Impaired cortical inhibition | Prolonged reaction times | [24] |

| Successful Aging (85+ yo) | Stabilization | Maintained neural specificity | Intact cognitive performance | [25] |

Individual participant meta-analysis reveals that age-related GABA differences follow a nonlinear trajectory, with stabilization in cognitively-intact oldest-old adults (85+ years). This flattening slope suggests a survivorship effect, where maintained GABAergic function may be neuroprotective and necessary for intact cognition in advanced age [25].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Core Research Protocols

Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) for GABA Quantification

Protocol: MEGA-PRESS MRS for GABA Measurement

Voxel Placement: Position 30×30×30 mm³ voxel in target region (e.g., visual cortex, frontal midline). Align precisely using structural landmarks [25].

Sequence Parameters: Implement MEGA-PRESS editing sequence with the following specifications:

- Editing pulses: ON at 1.9 ppm, OFF at 7.46 ppm

- TE: 68 ms, TR: 2000 ms

- Averages: 320 (160 ON, 160 OFF)

- Scan duration: 10:48 minutes

- Spectral width: 4000 Hz with 4096 data points [25]

Water Suppression: Apply chemical shift selective water suppression (CHESS) with transversal saturation band placed along the skull.

Data Processing:

- Analyze vendor-native data in Gannet 3.3.1 (MATLAB)

- Reference to creatine (Cr) or unsuppressed water signal (H₂O)

- Apply α-correction for gray/white matter differences

- Quality control: fit error <15%, visual inspection of spectra [25]

fMRI Neural Specificity Assessment

Protocol: Measuring Neural Specificity with fMRI

Stimulus Design: Present multiple categories of visual stimuli (e.g., faces, houses) in block or event-related design. Use HMAX computational modeling to objectively quantify stimulus complexity [16].

Image Acquisition: Acquire BOLD images with standard parameters (e.g., TR=2000ms, TE=30ms, voxel size=3×3×3mm³).

Neural Specificity Quantification:

- Extract activation patterns for each stimulus category

- Calculate pattern discriminability (e.g., Pearson correlation, Mahalanobis distance)

- Higher discriminability indicates better neural specificity [22]

Brain Signal Variability Analysis:

- Calculate moment-to-moment BOLD signal variability (SDBOLD)

- Compute variability modulation (ΔSDBOLD) as difference between complex and simple stimuli

- Relate variability measures to GABA levels and behavior [16]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for GABA-Neural Specificity Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GABA Agonists | Lorazepam | Pharmacological fMRI/MRS | GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulator | [16] |

| Viral Vectors | AAV-DIO-ChR2-eYFP | Optogenetics | Cre-dependent Channelrhodopsin expression | [23] |

| MRS Analysis Software | Gannet 3.3.1 | GABA quantification | MEGA-PRESS data processing | [25] |

| Computational Models | HMAX model | Visual stimulus analysis | Objective complexity quantification | [16] |

| Transgenic Animals | VGluT2-Cre mice | Circuit mapping | Selective targeting of glutamatergic neurons | [23] |

Research Workflow Integration

The integrated experimental approach to studying GABA's role in neural specificity combines neurochemical, functional, and behavioral assessments:

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The precise regulation of GABAergic signaling represents a promising target for therapeutic interventions in conditions characterized by degraded neural specificity:

Glaucoma and Neurodegenerative Disorders: The association between GABA reduction and degraded visual cortex specificity in glaucoma suggests GABAergic enhancers could preserve visual function beyond intraocular pressure management [22].

Age-Related Cognitive Decline: The demonstration that GABA stabilization correlates with successful cognitive aging in the oldest-old indicates that GABAergic therapies might prolong cognitive health [25].

Post-Stroke Motor Recovery: The correlation between motor cortex GABA levels and reaction time in subarachnoid hemorrhage patients suggests GABA modulation could improve motor recovery [24].

Precision Pharmacology: The inverted-U relationship between GABA levels and neural variability modulation indicates that therapeutic efficacy will depend on individual baseline GABA levels, necessitating patient stratification [16].

Future drug development should target specific GABA receptor subunits and regulatory mechanisms identified in recent studies, particularly the novel glutamate binding site on GABAA receptors [4] and the distinct release properties of co-transmitting neurons [23].

The Excitation/Inhibition (E/I) balance hypothesis posits that optimal sensory processing relies on a precise, dynamic equilibrium between excitatory (primarily glutamatergic) and inhibitory (primially GABAergic) neurotransmission. This balance is not static but is actively modulated by sensory input and is fundamental to encoding stimulus properties, shaping neural selectivity, and governing perceptual outcomes. The visual cortex serves as a predominant model for investigating these principles, with visual contrast response representing a key paradigm for quantifying how neural circuits adjust their gain and dynamic range to incoming information. Disruptions to this delicate balance are implicated in a range of neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders, underscoring the hypothesis's clinical relevance. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to provide an in-depth technical guide on the E/I balance in sensory processing, with a specific focus on the roles of glutamate and GABA in visual contrast response.

Neurotransmitter Dynamics in the Visual Cortex

GABA and glutamate, the principal inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitters in the central nervous system, exhibit distinct and often opposing dynamics during visual processing, which can be measured in vivo using functional Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (fMRS).

A pivotal fMRS study investigated the dynamics of GABA and the glutamate-glutamine complex (Glx) in the human occipital cortex across three functional states: eyes closed, eyes open in darkness, and visual stimulation [26]. The study revealed that compared to the eyes-closed baseline, GABA levels decreased when participants opened their eyes in darkness, whereas Glx levels remained stable [26]. During active visual stimulation, Glx levels increased, demonstrating a clear dissociation in the dynamics of these neurotransmitters in response to changing visual input [26].

The temporal dynamics of these neurotransmitters are also critical. Research tracking GABA+ and Glx over time in the visual cortex while participants were at rest (eyes closed) found that their concentrations drift in opposite directions; GABA+ decreases while Glx increases over time [9]. Furthermore, a predictive relationship was uncovered: the concentration of GABA+ predicts the concentration of Glx approximately 120 seconds later, such that a change in GABA+ is correlated with a subsequent opposite change in Glx [9]. This temporal interplay suggests a homeostatic mechanism where inhibition gates subsequent excitation over a specific time window, a phenomenon localized to the visual cortex and not observed in the posterior cingulate cortex [9].

Table 1: Dynamics of GABA and Glutamate in the Visual Cortex During Visual Processing

| Visual State | GABA Level | Glutamate/Glx Level | Correlation with fMRI/BOLD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eyes Closed (Baseline) | Baseline level | Baseline level | Not applicable |

| Eyes Open (Darkness) | Decreases [26] | Remains stable [26] | GABA and Glx correlate with the amplitude of fMRI signal fluctuations in relevant states [26] |

| Active Visual Stimulation | Not reported (studies show mixed results [9]) | Increases [26] | GABA and Glx correlate with the amplitude of fMRI signal fluctuations in relevant states [26] |

| At Rest (Over Time) | Decreases over time [9] | Increases over time [9] | Not applicable |

These neurotransmitter levels are not only state-dependent but also directly linked to perceptual performance. In the visual cortex, the level of GABA, but not Glx, has been found to correlate with visual discriminatory performance, highlighting the specific role of inhibitory neurotransmission in refining perceptual acuity [26].

E/I Balance and Contrast Response Functions

Contrast response functions (CRFs) describe how neural activity changes with the contrast of a visual stimulus and serve as a key metric for probing E/I balance in the visual system. The shape of the CRF is determined by the complex interaction between excitatory and inhibitory inputs.

In the early visual cortex (e.g., V1), neural ensembles exhibit a quasi-linear CRF, where response increases proportionally with contrast [27]. This linearity at the population level can be understood as an aggregate of individual neurons with compressive nonlinear CRFs that have different contrast-gain characteristics [27]. At higher cortical levels (e.g., V2, V4), CRFs become markedly nonlinear, characterized by response amplification at low contrasts and saturation at high contrasts [27]. This amplification is particularly effective over the range of contrasts most common in natural scenes (0.0 to 0.3) [27].

The differential CRFs across cortical hierarchies suggest that E/I balance is implemented differently at each level. In early, stimulus-dependent regions, neural responses track physical contrast linearly, while in higher, percept-related regions, responses are amplified and saturated, reflecting the transition to processing perceptual attributes [27]. Therefore, the shape of a psychophysically or physiologically measured CRF can indicate the relative level of cortical processing underlying a visual phenomenon. A quasi-linear CRF suggests a greater contribution from early/low-level processing (e.g., V1), while a compressive nonlinear CRF implies involvement of higher cortical levels [27].

Table 2: Characteristics of Contrast Response Functions (CRFs) Across Cortical Levels

| Cortical Level | CRF Shape | Proposed Neural Basis | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early (e.g., V1) | Quasi-linear [27] | Averaging of individual neurons' nonlinear CRFs with different contrast gains [27] | Linear tracking of physical stimulus contrast; stimulus-dependent [27] |

| Higher (e.g., V2, V4) | Compressive Nonlinear (amplification at low contrasts, saturation at high contrasts) [27] | Pooling of inputs from lower levels via probability summation [27] | Representation of perceptual brightness contrast; percept-related [27] |

The relationship between neural firing and hemodynamic signals used in neuroimaging (like the BOLD signal in fMRI or intrinsic optical signals) is also nonlinear. In cat primary visual cortex, the CRF measured by optical imaging saturates at lower contrasts than the CRF derived from single-unit recordings [28]. This indicates that hemodynamically driven signals represent a more complex signature of neural activity than just firing rates, potentially reflecting metabolic demands and subthreshold activity [28].

Computational Models and Emergent Properties

Computational modeling provides a powerful tool to formalize the E/I balance hypothesis, generate testable predictions, and bridge scales from cellular mechanisms to system-level observations.

Neural Population Models of E-I Balance

Computational models based on leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neurons have been used to simulate the effects of varying E/I balance on cortical activity. These models typically consist of populations of excitatory (pyramidal) and inhibitory neurons [29]. Simulations have demonstrated that increasing the level of background "noise" – modeled as randomly timed excitatory inputs mediated by AMPA receptors – leads to a higher level of excitation in the E/I balance, resulting in a stronger local field potential (LFP, a proxy for EEG), greater NMDA current in pyramidal cells, and an increased spike rate [29]. This provides a mechanistic link between the cellular level and the systemic level, showing how increased noise can lead to aberrant excitation, which is observed in conditions like schizophrenia [29].

E-I Balance in Chronic Pain Circuits

While not in the visual cortex, the analysis of E-I balance in dorsal horn neural subcircuits mediating allodynia (a chronic pain symptom) offers a clear example of how circuit dysregulation leads to pathology. Computational models of these subcircuits indicate that disruption of E-I balance occurs primarily through two mechanisms: downregulation of inhibitory signaling, which "releases" excitatory neurons from inhibitory control, or upregulation of excitatory neuron responses, allowing them to "escape" inhibitory control [30]. The specific mechanism and subcircuit components involved vary, predicting the high interindividual variability observed in allodynia [30].

Emergent Categorization from Object Recognition

Further supporting the role of experience-dependent processing in shaping neural representations, a convolutional neural network (CNN) trained for object recognition on natural images developed a categorical representation of color at the level where objects are represented for classification [31]. When probed with a color classification task, the network's internal representations showed largely invariant color category borders, even when the training colors for the classifier were shifted [31]. This suggests that the development of basic visual skills, such as object recognition, can contribute to the emergence of categorical perception without an explicit communicative drive, providing a model for how E-I interactions in hierarchical circuits can give rise to perceptual categories [31].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Functional Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (fMRS)

Objective: To measure the dynamics of neurometabolites (GABA and Glx) in the human visual cortex during different states of visual processing.

Protocol Details:

- Participants: Healthy adults with normal or corrected-to-normal vision, screened for MRI contraindications [9].

- Stimuli & Task: Participants are exposed to blocks of different visual conditions in the scanner: (1) Eyes closed (baseline), (2) Eyes open in darkness, and (3) Active visual stimulation (e.g., a checkerboard pattern or movie) [26]. For resting state dynamics, participants simply keep their eyes closed for the duration of the scan [9].

- Data Acquisition: Spectra are acquired using a MEGA-PRESS sequence on a 3T MRI scanner [9]. Example parameters: TE = 68 ms; TR = 3000 ms; 256 transients; a 14.28 ms Gaussian editing pulse is applied at 1.9 ppm (ON) and 7.5 ppm (OFF) for GABA editing [9]. Automated and manual shimming is conducted to achieve a narrow water linewidth (e.g., ~12 Hz) [9]. A T1-weighted anatomical scan is acquired for precise voxel placement in the visual cortex [26].

- Data Analysis: Spectra are analyzed using specialized software (e.g., Gannet, LCModel) to quantify the concentration of GABA+ (including macromolecules) and Glx. For dynamic analyses, a moving average window (e.g., ~6 minutes) is used to reveal low-frequency trends, or data is combined across participants to achieve higher temporal resolution [9]. Concentrations are often reported relative to the internal water signal or creatine.

Contrast Response Function (CRF) Mapping

Objective: To characterize the relationship between visual stimulus contrast and neural response across different cortical areas.

Protocol Details:

- Animal Model (e.g., cat): Animals are anesthetized and prepared for physiological recording. Vital signs are monitored and maintained within a normal physiological range [28].

- Stimuli: Visual stimuli (e.g., moving gratings) are presented on a monitor. The orientation and/or direction of motion are fixed for a given recording site. The contrast of the grating is varied systematically across a range (e.g., from 0% to 100%) in a randomized order [28].

- Data Acquisition - Electrophysiology: Single-unit or multi-unit activity is recorded extracellularly using metal microelectrodes inserted into the visual cortex (e.g., area 18) [28]. The mean firing rate in response to each contrast level is calculated.

- Data Acquisition - Intrinsic Optical Signal Imaging: The cortical surface is illuminated with light, and a camera captures changes in light reflectance. Differential images are created by subtracting images obtained during presentation of one stimulus direction/orientation from those of the opposite direction/orientation [28]. The magnitude of the optical signal is quantified for each contrast level.

- Data Analysis: Response versus contrast data are plotted and fitted with a Naka-Rushton function or similar sigmoidal curve to derive parameters like baseline response, semi-saturation contrast (C~50~), and maximum response [27] [28]. CRFs from different measurement techniques (electrophysiology vs. optical imaging) or different cortical areas are compared.

Signaling Pathways and Neural Circuits

The following diagram illustrates the core E/I signaling pathway in a canonical cortical microcircuit, as observed in sensory processing regions like the visual cortex.

Diagram 1: Core E/I Signaling in a Cortical Microcircuit. The pathway shows how sensory input drives glutamate release, activating both excitatory pyramidal neurons and inhibitory interneurons. The inhibitory interneurons release GABA, which provides feedback inhibition to the pyramidal neurons. The dynamic interaction between these excitatory (blue) and inhibitory (red) signals establishes the E/I Balance (yellow), which controls the gain and precision of the network's output.

The experimental workflow for investigating E/I balance and contrast response integrates the methodologies described above, as outlined in the following diagram.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for E/I and Contrast Response Research. The workflow begins with subject/animal preparation and stimulus presentation. Data is acquired through one or more neuroimaging or electrophysiology techniques. The resulting data are analyzed to extract quantitative metrics (neurotransmitter levels, hemodynamic responses, neural firing rates/CRFs), which are then integrated, often with the aid of computational models, to form a comprehensive assessment of E/I balance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for E/I Balance and Contrast Response Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Key Details / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 3T/7T MRI Scanner with MEGA-PRESS | In vivo quantification of GABA and Glx concentrations in the human brain. | MEGA-PRESS is an edited MRS sequence specifically designed for detecting low-concentration metabolites like GABA. Higher field strength (7T) improves signal-to-noise ratio and spectral resolution [26] [9]. |

| fMRI-Compatible Visual Stimulation System | Presentation of controlled visual stimuli (e.g., contrast gratings, movies) during scanning. | Allows for correlation of neurotransmitter dynamics or BOLD signals with specific visual processing states. Systems must be non-magnetic and often use projectors or LCD screens viewed via a mirror [26]. |

| Intrinsic Optical Signal Imaging Setup | Mapping of functional architecture and contrast responses in animal models. | Involves a light source, high-sensitivity camera, and data acquisition software to capture activity-dependent changes in cortical reflectance. Provides high spatial resolution for columnar-level mapping [28]. |

| Extracellular Recording Electrophysiology | Measuring action potential firing rates of single neurons or neural populations in response to contrast. | Uses metal or glass microelectrodes to record neural activity in vivo. The gold standard for directly relating stimulus contrast to neural output and constructing CRFs [28]. |

| Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) Model | Computational simulation of E/I balance in neural populations. | A simplified spiking neuron model used to simulate network dynamics, investigate the effects of noise, and test hypotheses about circuit-level dysregulation of E/I balance [29]. |

| Psychophysics Toolbox | Design and control of visual psychophysical experiments in humans. | A software library (for MATLAB or Python) that provides routines for generating precise visual stimuli and managing task timing, crucial for linking neural E/I balance to perceptual performance [26] [27]. |

Probing the Living Brain: MRS and fMRI Methodologies for Visual Neurochemistry

The quest to understand the complex relationship between brain neurochemistry and hemodynamics represents a central challenge in modern neuroscience. Combined functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (fMRI-MRS) has emerged as a revolutionary approach that enables simultaneous acquisition of hemodynamic and neurochemical measures during brain activation [32]. This advanced neuroimaging technique provides unprecedented insights into the neurovascular and neurometabolic coupling that underlies brain function, offering a more comprehensive understanding of neural activity than either method could provide alone.

Within the specific context of visual cortex contrast response research, combined fMRI-MRS offers a powerful tool for investigating the roles of the brain's primary excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters—glutamate and GABA—in shaping visual processing. By capturing dynamic changes in these neurotransmitters alongside traditional blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals, researchers can directly probe the excitatory-inhibitory balance that governs neural responses to visual stimuli [33]. This technical guide explores the principles, methodologies, and applications of combined fMRI-MRS, with particular emphasis on its transformative potential for visual neuroscience and drug development.

Technical Foundations of Combined fMRI-MRS

Fundamental Principles

Combined fMRI-MRS represents a significant technological advancement that addresses fundamental limitations of each individual method. While BOLD-fMRI measures changes in blood oxygenation as an indirect proxy of neural activity, it cannot differentiate between excitatory and inhibitory neural processes or provide direct information about neurotransmitter dynamics [33]. Conversely, traditional MRS quantifies static neurochemical concentrations but typically lacks the temporal resolution to track rapid changes associated with neural processing.

The integrated approach of combined fMRI-MRS leverages recent advancements in high-field MR systems to simultaneously capture both types of information within the same repetition time (TR). This simultaneous acquisition is crucial as it ensures that hemodynamic and neurochemical measurements reflect identical brain states and experimental conditions, eliminating potential confounds associated with sequential measurements [32]. The core innovation lies in specialized pulse sequences that interleave BOLD-fMRI and MRS acquisitions, typically with a brief delay (e.g., 250 ms) to minimize potential eddy current effects from the echo-planar imaging (EPI) readout [32].

Key Neurochemical Targets in Visual Processing

For visual cortex contrast response research, two neurotransmitters are of particular importance:

Glutamate: As the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, glutamate drives neural activation in response to visual stimuli. Task-related increases in visual cortex glutamate concentrations reflect heightened excitatory neurotransmission during visual processing [32] [33].

GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid): As the main inhibitory neurotransmitter, GABA regulates and sharpens neural responses, contributing to contrast gain control and other normalization processes in visual perception [34] [33].

The dynamic balance between glutamate and GABA (the E/I balance) is essential for efficient visual information processing, and combined fMRI-MRS provides a unique window into this relationship during controlled visual stimulation.

Experimental Design and Protocol Specifications

Simultaneous Acquisition Parameters

The following table summarizes key parameters from a seminal 7T fMRI-MRS study investigating visual cortex responses to flickering checkerboard stimuli:

Table 1: Experimental Parameters for Combined fMRI-MRS at 7T [32]

| Parameter Category | Specific Setting | Additional Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MR System | 7T whole-body scanner (Siemens) | Single transmit, 32 receive channels head coil |

| BOLD-fMRI Acquisition | 3D EPI, resolution=4.3×4.3×4.3 mm; TE=25 ms; TR=4 s; 16 slices | Flip angle=5°; FOV=240 mm |

| MRS Acquisition | Short-echo semi-LASER; TE=36 ms; TR=4 s | VAPOR water suppression; outer volume suppression |

| Visual Stimulation | Block design (64 s cycles); contrast-reversing checkerboard (8 Hz flicker) | 4 stimulation blocks interleaved with baseline; central fixation task |

| Voxel Placement | 2×2×2 cm in occipital lobe | Centered along midline and calcarine sulcus |

| Special Considerations | Dielectric pad (BaTiO3/deuterated water) behind occiput | Improves transmit field efficiency (>100%) in target region |

Visual Stimulation Paradigms

Effective visual stimulation paradigms for combined fMRI-MRS studies of contrast response should incorporate several key design considerations:

Block duration: Short blocks (e.g., 64 s) are effective for capturing transient neurochemical changes while maintaining practical experiment duration [32].

Stimulus characteristics: Contrast-reversing checkerboards effectively target the visual cortex with minimal generalization to other cortical regions [32]. For color processing investigations, uniform color stimuli or chromatic gratings can be employed to selectively activate color-sensitive neurons [35].

Control conditions: Appropriate baseline conditions (e.g., uniform gray or black screens) are essential for quantifying stimulus-induced changes.

Attention control: Incorporating a simple performance task (e.g., detecting color changes in a fixation dot) helps maintain consistent attention levels across participants [32].

Data Processing and Analytical Approaches

Advanced processing pipelines are required for analyzing combined fMRI-MRS data:

fMRI preprocessing: Standard pipelines including motion correction, spatial smoothing, temporal filtering, and statistical parametric mapping [32].

MRS processing: Quality assessment based on spectral quality metrics (e.g., signal-to-noise ratio, linewidth), followed by quantitative analysis using specialized tools like LCModel [34].

Integrated analysis: Correlation analyses between BOLD and neurotransmitter time courses; statistical comparison of metabolite concentrations during stimulation versus baseline periods [32].

Table 2: Representative Neurochemical and Hemodynamic Changes During Visual Stimulation [32]

| Measurement Type | Baseline Condition | Stimulation Condition | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| BOLD-fMRI Signal | Baseline level | 1.43±0.17% increase | Significant (p<0.05) |

| Glutamate Concentration | Baseline level | 0.15±0.05 I.U. increase (~2%) | Significant (p<0.05) |

| BOLD-Glutamate Correlation | Not applicable | R=0.381 | p=0.031 |

| Glutamate (Sham Stimulation) | No significant change | No significant change | Not significant |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of combined fMRI-MRS requires specific hardware, software, and experimental components:

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Combined fMRI-MRS Experiments

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| High-Field MR System | 7T scanner with multi-channel head coil | Provides necessary signal-to-noise ratio and spectral resolution for detecting neurochemical changes |

| Dielectric Padding | BaTiO3/deuterated water suspension pad | Enhances transmit field efficiency in target brain regions (>100% improvement) [32] |

| Specialized Pulse Sequences | semi-LASER (Localization by Adiabatic Selective Refocusing) | Enables precise spatial localization with minimal chemical shift displacement [32] |

| Visual Presentation System | MRI-compatible projection systems with high luminance stability | Preserves precise visual stimulus characteristics in the MR environment |